This week’s machine was Poison from Hack the Box, a FreeBSD machine rated as medium. I don’t know much about FreeBSD, so it was interesting learning about some of the differences between it and more popular Linux versions. Also I got to practice SSH tunneling, so that was fun.

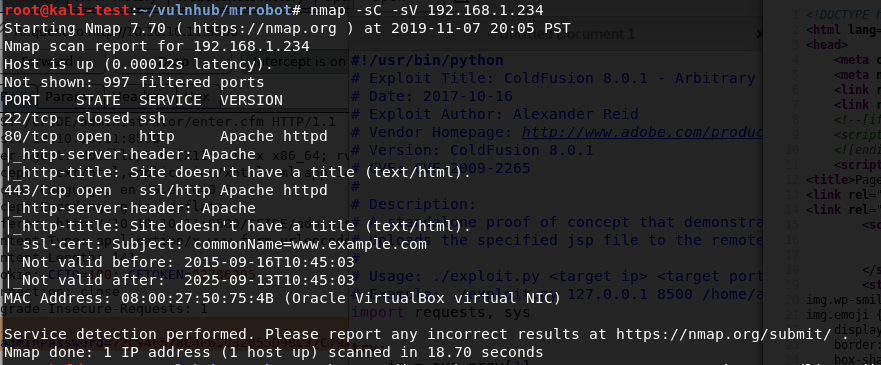

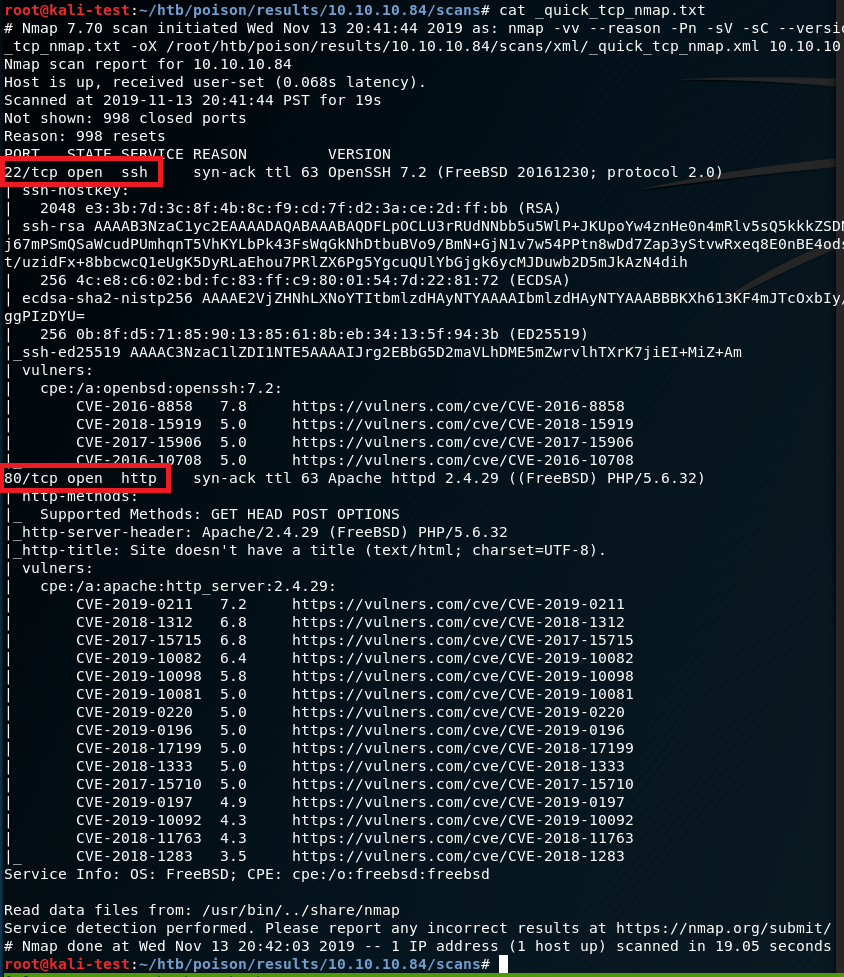

Running the initial nmap scan shows two ports open: ssh on 22 and http on 80. The additional information shows OpenSSH version 7.2 for FreeBSD from 2016 and a Google search for Apache 2.4.29 shows a release in late 2017. Both of these are pretty old at this point, so we’ll keep that in mind later if we don’t find an obvious exploit.

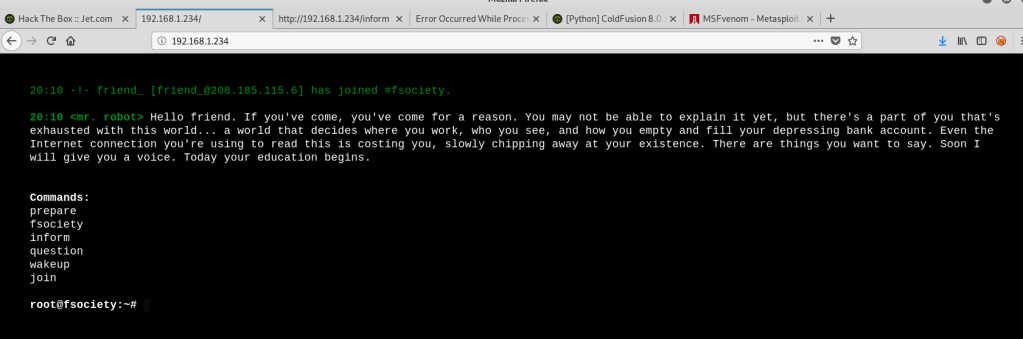

Moving over to the browser to check out the web page, we find something that appears to be used for testing PHP scripts on the server. The sites listed to be tested look interesting, so let’s see if they’re in the root directory.

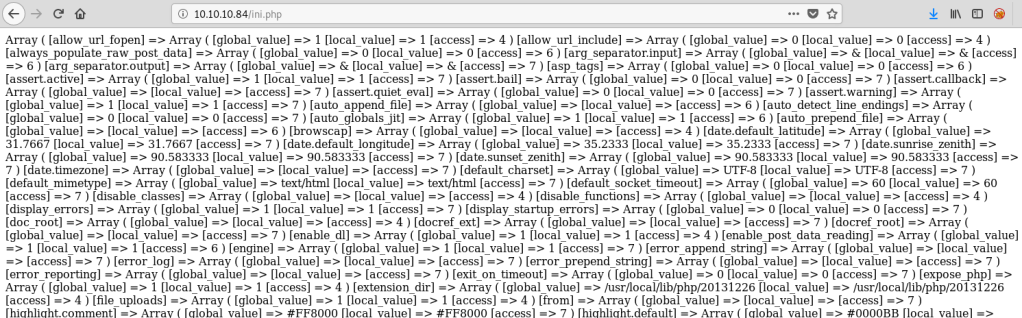

Each page loads successfully, with ini.php appearing to be some type of configuration file.

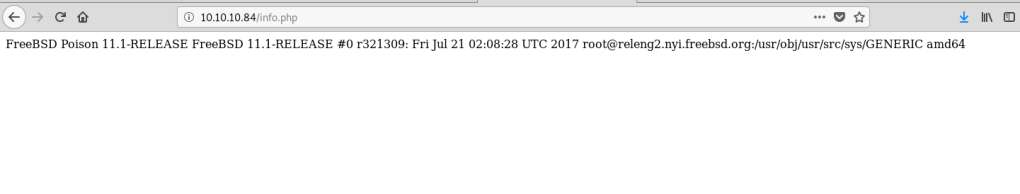

Info.php appears to be the result of running ‘uname -a’ on the server, listing kernel information.

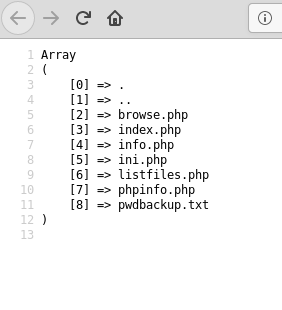

Listfiles.php shows an array of items, mostly matching the list of files to be tested on the home page. Of particular interest to us is the ‘pwdbackup.txt’ file that wasn’t listed before.

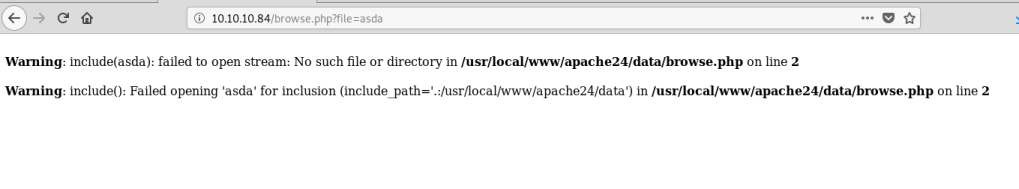

Before checking out the pwdbackup.txt file, I was curious what happened if I tried to search for something in the field on the home page. Based on the page below I noticed two things: 1) it’s adding my search term as a parameter in the URL which might be vulnerable to RFI/LFI/directory traversal and 2) it appears to be searching the current directory for a file matching the term I searched for (in this case ‘asda’).

I didn’t find much of value through #2 above, but the page did turn out to be vulnerable to a directory traversal, allowing me to view the /etc/passwd file on the server. However, the web server appeared to be running under a lower privileged account as I was not able to view more sensitive files such as /etc/shadow.

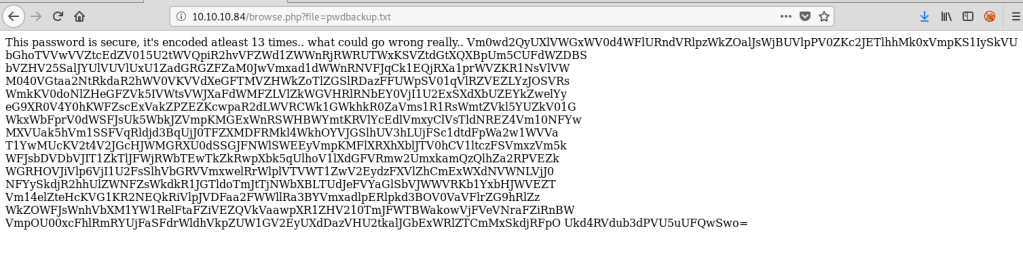

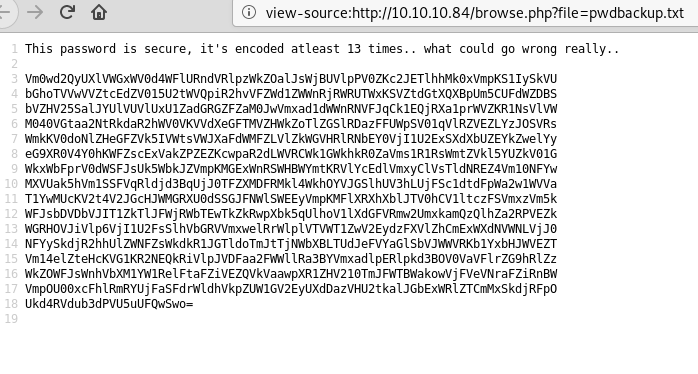

The passwd file was useful in that it gave us a list of users on the box, but I wasn’t able to view much else. On the other hand, when checking out /pwdbackup.txt we see what appears to be a password that has been encoded 13 times.

The encoded string looks like regular base64, so a quick bash command to duplicate ‘| base64 -d’ 13 times, then piping the string to this reveals the decoded password.

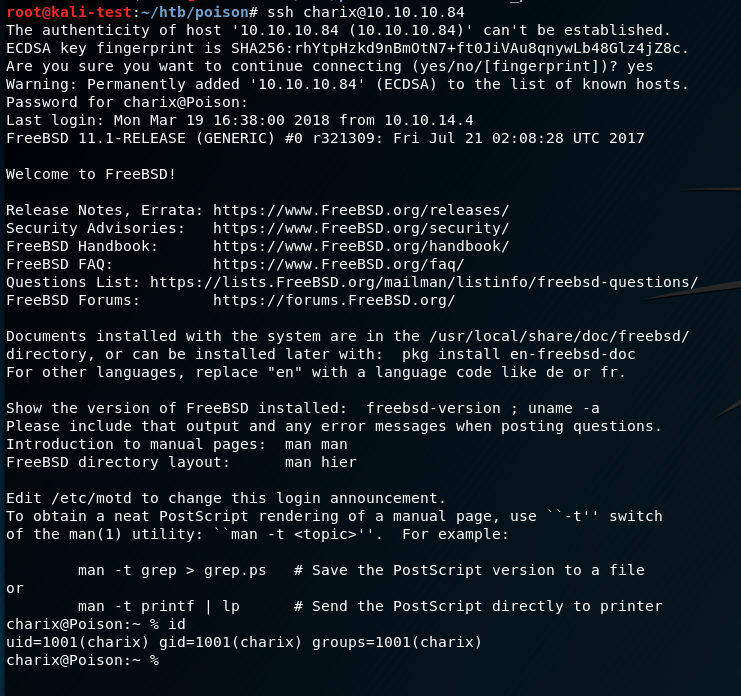

Looking at this password, and comparing it to the list of users we saw in /etc/passwd, we see a common name of ‘charix’. Assuming this password is for the user with the same name, I was able to ssh into the machine with that account.

Success! With that we have access to the user flag.

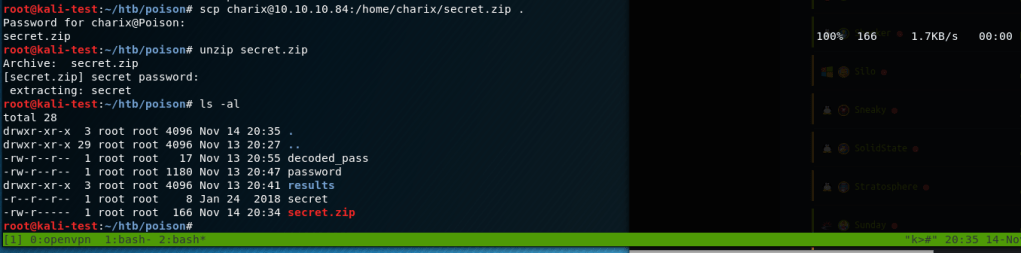

It looks like the home directory for charix also has a file named ‘secret.zip’, which sounds interesting. I downloaded a copy of it with scp and unzipped it. It asked for a password, but it ended up using the same one as the charix user.

Looking at the content of the secret file, it seems to be a binary that’s not readable. Not much to go on there, so let’s move on to see what else there is to find on the box that charix can see.

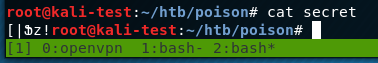

Getting running processes with ps -aux shows an instance of tightvnc is running as root. Interesting.

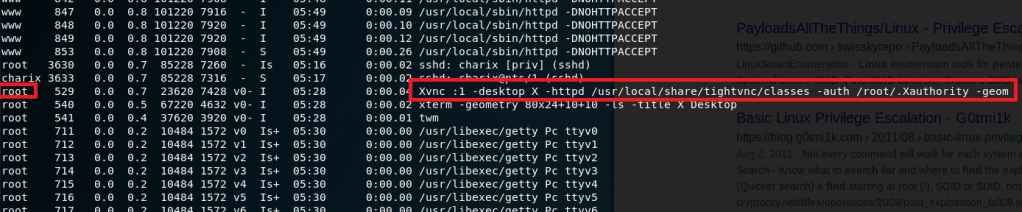

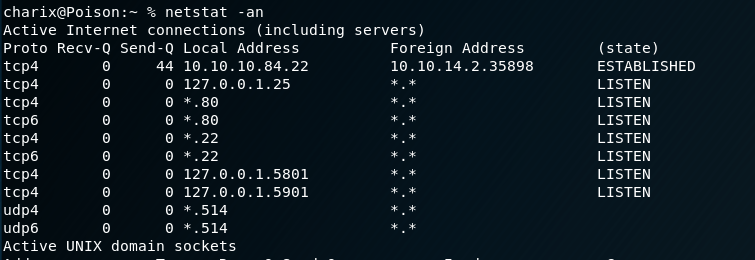

Using netstat, we can also see the box is listening on ports 5801 and 5901 on localhost, which are commonly used for VNC (5901) and VNC over HTTP (5801). This is likely our vector for privilege escalation, but the service is only available on the local machine, which means we’ll need to use some port forwarding to be able to access it.

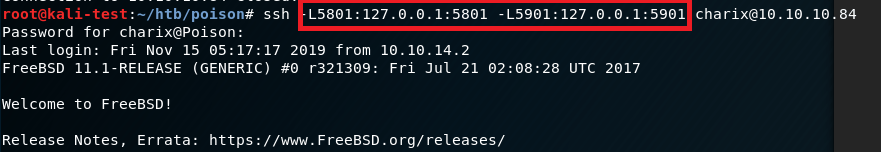

I chose to do this through SSH tunneling using the command above to forward both 5801 and 5901 on the box to the matching ports on my machine.

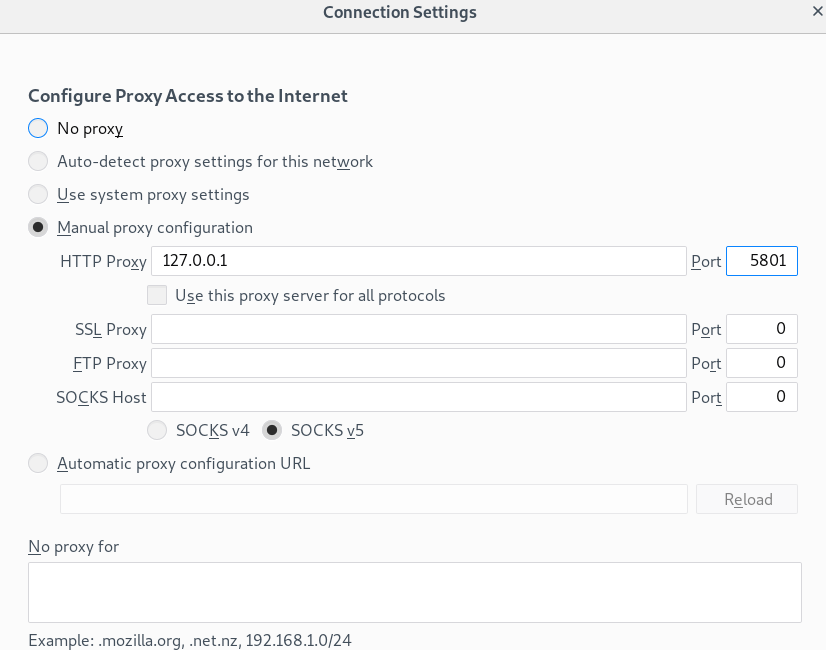

Running netstat on my machine afterward confirms we’re now listening on both ports for VNC. To confirm we can actually access the service, I modified the proxy settings in Firefox and tried to visit my localhost on these ports.

5801 shows a “File Not Found” message, which doesn’t give us anything, but does at least prove it’s listening correctly as it didn’t give a “Page not found”.

Changing the proxy settings to 5901 and trying again gives the image below, which is standard for VNC, though I’m not sure what it means. Ok, so now we’ve confirmed we can successfully access the VNC service on the remote machine through our local ports. Now we can try to connect directly with VNC.

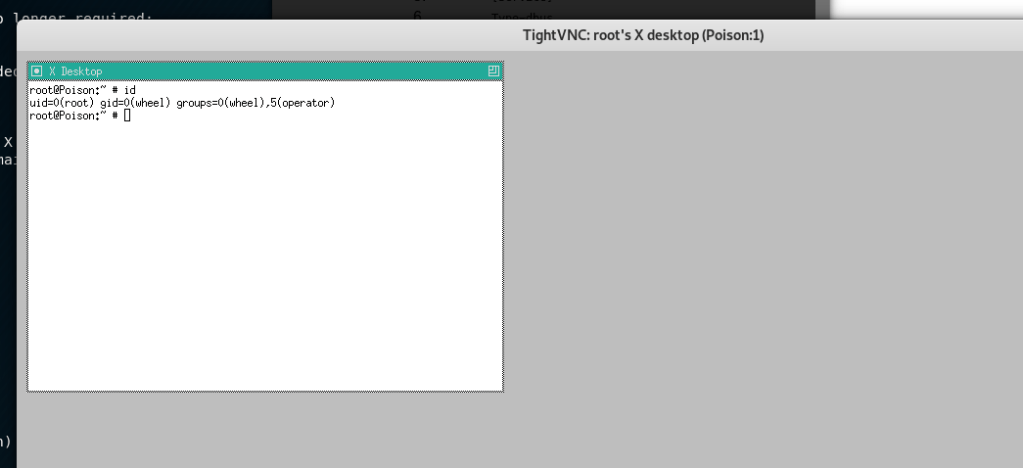

Normally, we would need to know the password for a VNC session, but TightVNC actually has an option to provide a file as the password for a session. The secret file found earlier sounds more relevant now.

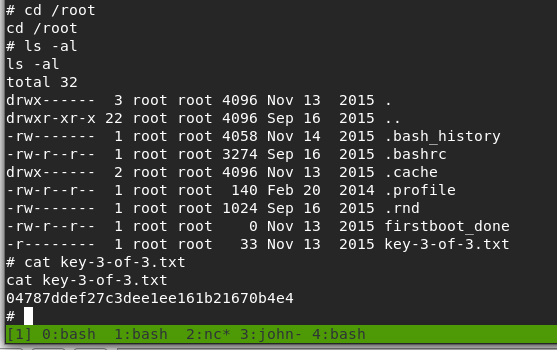

Running TightVNC, with the secret file as the password, we’re able to successfully connect to the VNC session and it looks like we’re now running as root. Huzzah!

That’s all for this one, so, until next time.

Recommendations

It’s hard to suggest realistic recommendations for some of these machines that are obviously set up to be so unrealistic. We’ll give it a shot though.

- Leaving a web application that has access to read local files on the web server is obviously a bad idea. Ideally this should only be used in a development environment and removed for production. However, if for some reason this functionality is needed in the final product, it should require authentication before users are able to access it.

- Passwords should not be re-used. If sensitive files are stored on a machine other users might be able to access, the password to access them should be different than the user’s regular password.