As we move through the book, I’m noticing myself starting to become more comfortable reading assembly and able to recognize what some functions do more quickly. It still takes me a long time (and a good bit of googling sometimes) to figure out what exactly is happening at the assembly level, but hey, it’s progress.

Chapter 6 was interesting in that it takes the basic aspects of a programming language (in this case C) and shows how they are implemented in Assembly to help an analyst pick out the patterns more easily. It covers some of the concepts I’m already familiar with, at least at a basic level, such as if statements, loops, and arrays, but also adds a little more complexity with structs and linked lists. I had to look up some of the C syntax for structs and linked lists to get a better idea of why they’re formatted like they are, but it at least makes enough sense for me to get through the labs now.

Lab 6-1 (Lab06-01.exe)

Question 1: What is the major code construct found in the only subroutine called by main?

It’s an if statement that prints a message depending on the outcome of the “InternetGetConnectedState” function. If the function returns 0, it will print a message stating there is no internet, otherwise it will print a message indicating the computer has an internet connection.

Question 2: What is the subroutine located at 0x40105F?

As the subroutine follows the push of the strings mentioned above, it is likely printing the string to the shell. This is confirmed when running the program from the command line.

Question 3: What is the purpose of this program?

The purpose seems to be just to check the internet connection of the computer it is running on and print a success/failure message.

Lab 6-2 (Lab06-02.exe)

Question 1: What operation does the first subroutine called by main perform?

The first subroutine called is sub_401000 and performs the check for an internet connection that was used in Lab6-1.

Question 2: What is the subroutine located at 0x40117F?

This seems to have the same function as sub_40105F in the last lab. It seems to print the result of the internet connectivity check to the screen.

Question 3: What does the second subroutine called by main do?

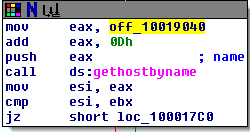

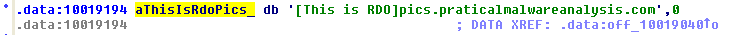

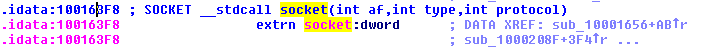

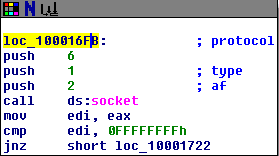

The second subroutine, sub_401040, is called if there is an internet connection and tries to connect to the URL “http://www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com/cc.htm”. If it successfully connects to the site it will attempt to read the cc.htm file and, if there is an HTML comment in the file, read a command from after the comment. The second screenshot below shows the steps it takes on the right hand side to iterate through an array of the characters in the html file. If it reads the first three characters as “<!–“, or the beginning of a comment, it will store the next character as the command. If any of these steps fail it will print an error message.

Question 4: What type of code construct is used in this subroutine?

This subroutine uses an array to store information read from an html file to try and retrieve a command. It iterates over the html file looking for a comment at the beginning (starting with the characters “<!–“).

Question 5: Are there any network-based indicators for this program?

The network-based indicator would be an attempted connection to “http://www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com/cc.htm” or the user-agent it creates to connect to the URL “Internet Explorer 7.5/pma”.

Question 6: What is the purpose of this malware?

This malware builds on the first from Lab 6-1 by checking for an internet connection and, if so, attempting to connect to a URL to get a command from a file stored there. If it is able to connect and successfully retrieve a command it will then sleep for 60 seconds.

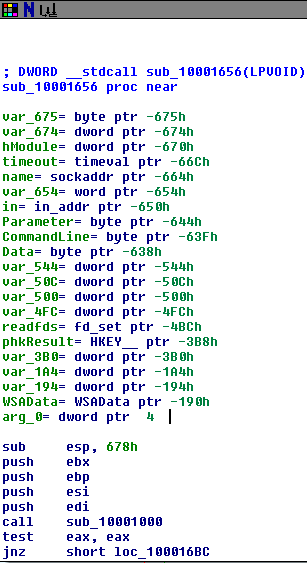

Lab 6-3 (Lab06-03.exe)

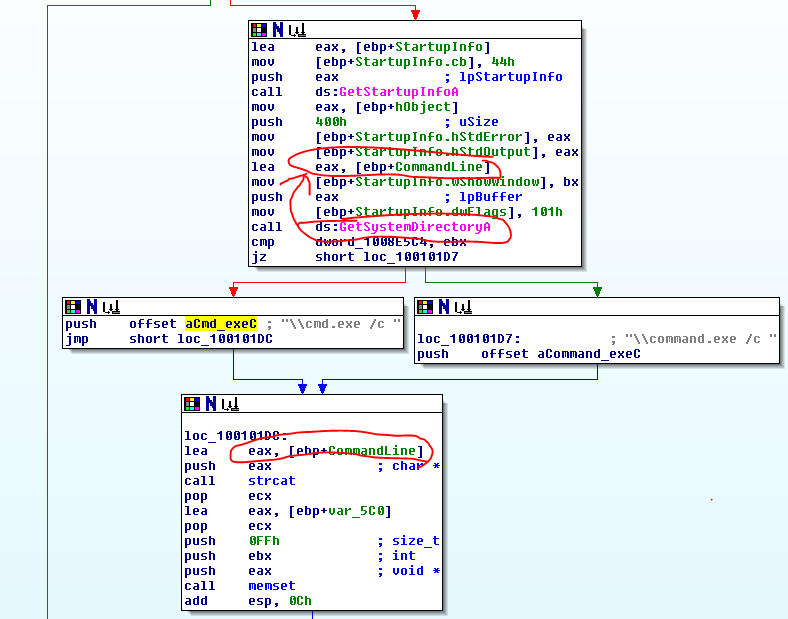

Question 1: Compare the calls in main to Lab 6-2’s main method. What is the new function called from main?

The new function called is sub_401130, which can create a directory, create/delete a file, create a registry key, sleep for 100 seconds, or print an error depending on which command it is passed.

Question 2: What parameters does this new function take?

The sub_401130 function takes two parameters: the command character parsed from the previous function and “argv[0]” which is a standard parameter for the main function and isn’t very useful for us.

Question 3: What major code construct does this function contain?

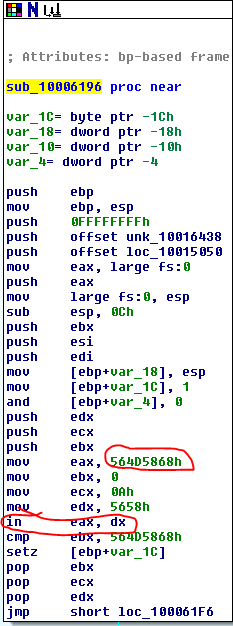

This function uses a switch statement.

Question 4: What can this function do?

Depending on the file name parameter passed, this function can: create a Temp directory, create the new file cc.exe in the Temp directory, delete the file from the Temp directory, create a registry key to have the cc.exe file run on startup, set the program to sleep for 100 seconds, or try to read a command from the website again.

Question 5: Are there any host-based indicators for this malware?

The two host-based indicators would be the malicious file at C:\Temp\cc.exe or the registry key “Malware” under HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run.

Question 6: What is the purpose of this malware?

This malware starts the same as the first two labs by checking for an internet connection, connecting to a website to download a file and get a command, then, depending on the command, will perform one of the actions from question 4.

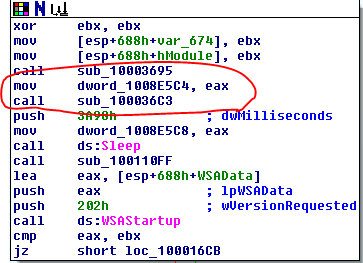

Lab 6-4 (Lab06-04.exe)

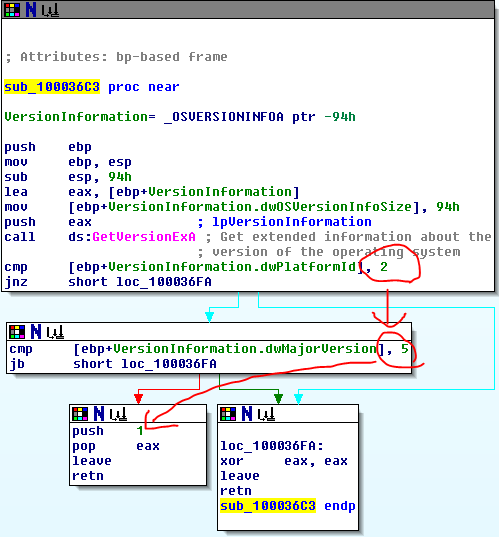

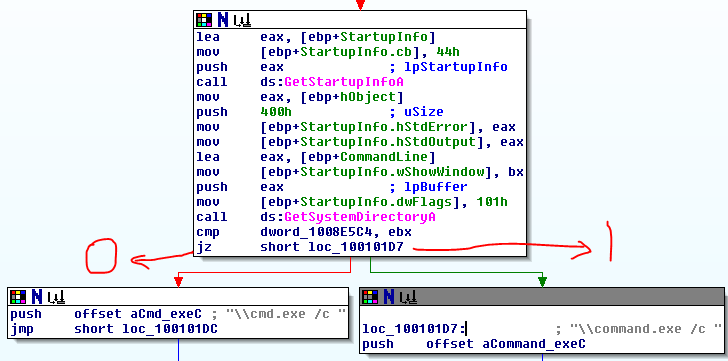

Question 1: What is the difference between the calls made from the main method in Labs 6-3 and 6-4?

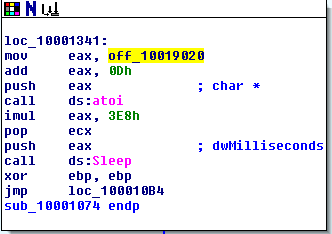

The main function now includes a loop that will continue trying to connect to the website and get a command until var_C is greater than or equal to 1440.

Question 2: What new code construct has been added to main?

A for loop.

Question 3: What is the difference between this lab’s parse HTML function and those of the previous lab?

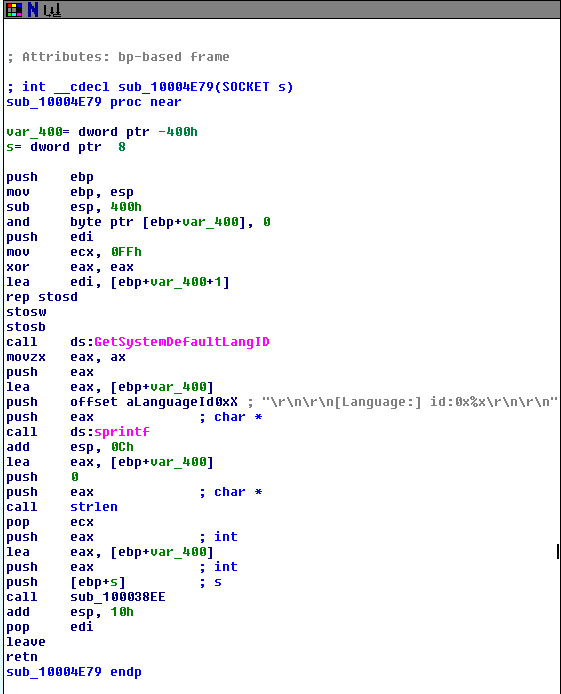

It takes a parameter now, the counter from the main function, and calls _sprintf when creating the user agent to add the parameter passed to the end of the agent string. This makes the agent string dynamic, allowing the malware creator to track how long it has been running.

Question 4: How long will this program run? (Assume that it is connected to the Internet.)

24 hours. Each time it goes through the process it sleeps for 60 seconds after successfully parsing a command and the while loop runs while the incremental value is less than 1440 (and 1440 minutes is equal to 24 hours).

Question 5: Are there any new network-based indicators for this malware?

The user-agent changes depending on how long the malware has been running. An indicator could be to look for the agent “Internet Explorer 7.50/pma%d”.

Question 6: What is the purpose of this malware?

The malware starts working the same way as the previous labs by checking an internet connection, parsing an html page for a document starting with a comment (“<!–“), reads the comment for a command to pass to the malware and chooses between multiple options based on the command received. Where this version differs is that it implements a for loop in the main function that will continue to run (if there is still an internet connection) for 24 hours. It also modifies the user agent used when parsing the website by adding a number to the end of the string that matches how long the program has been running. If it doesn’t find an internet connection on any iteration, the program terminates.