Chapter 4 starts off with a brief explanation of the different types of programming languages (machine code, low-level/assembly, high-level, and interpreted) and how their interaction with the computer differs. I’ve dabbled in various interpreted languages, such as Python and Java, and even experimented with a high-level language like C, but I’m not what I’d call proficient in any of them. Assembly code is an entirely different beast. The book focuses on assembly code for the x86 architecture, which is what most 32-bit personal computers use, so the book is showing it’s age a little bit in this regards, but it says x64 will be covered briefly in a later chapter.

I’m not going to try and explain how assembly code works as it still seems like mostly black magic to me at this point. I’ve had a little exposure to reading and manipulating assembly code when practicing buffer overflows in “Penetration Testing: A Hands-On Introduction to Hacking” by Georgia Weidman, and this book covers much of the same basic information, but the chapter 5 labs definitely left me feeling a lot more comfortable with at least the basics and how to navigate it using IDA.

Chapter 4 doesn’t have any labs as it’s just an introduction to assembly and the chapter 5 labs focus on practical application of that knowledge.

Chapter 5 is entirely devoted to the IDA Pro disassembly application by Hex-Rays. There is only 1 lab for this chapter, but that one lab has 21 questions to ensure we get a lot of experience poking around the tool.

Lab 5-1 (Lab05-01.dll)

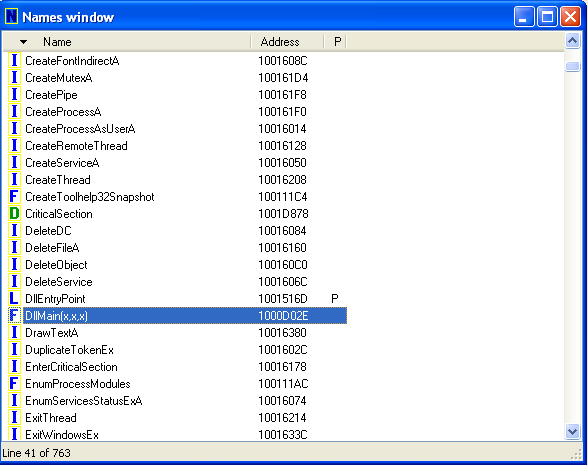

Question 1: What is the address of DllMain?

0x10000D02E

Question 2: Use the Imports window to browse to gethostbyname. Where is the import located?

“gethostbyname” is located in the WS2_32 library at address 0x100163CC in memory.

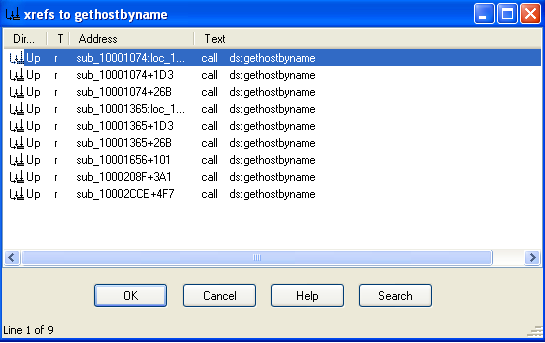

Question 3: How many functions call gethostbyname?

By searching for cross-references to the gethostbyname import, we see it is referenced 9 times.

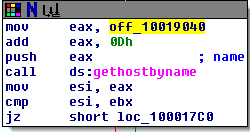

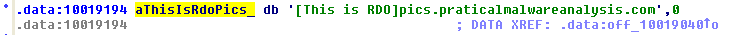

Question 4: Focusing on the call to gethostbyname located at 0x10001757, can you figure out which DNS request will be made?

When looking at this call, we see the first instruction is to move the data stored in offset 10019040 into eax and then add 0xD to it. If we double-click on the offset, it shows us the data stored in that location – “[This is RD0]pics.practicalmalwareanalysis.com”. Adding 0xD (13) to this, we get “pics.practicalmalwareanalysis.com” as the address the program is trying to resolve.

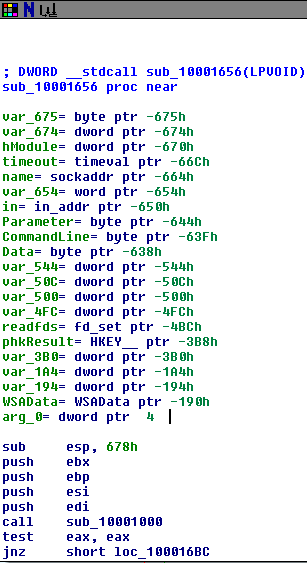

Question 5: How many local variables has IDA Pro recognized for the subroutine at 0x10001656?

IDA recognizes 20 local variables at this address. The book says there are 23 variables, so it seems IDA Free has a 20 variable limit.

Question 6: How many parameters has IDA Pro recognized for the subroutine at 0x10001656?

IDA found 1 parameter. See “arg_0” in the screenshot above.

Question 7: Use the Strings window to locate the string \cmd.exe /c in the disassembly. Where is it located?

It’s located at 0x10095B34.

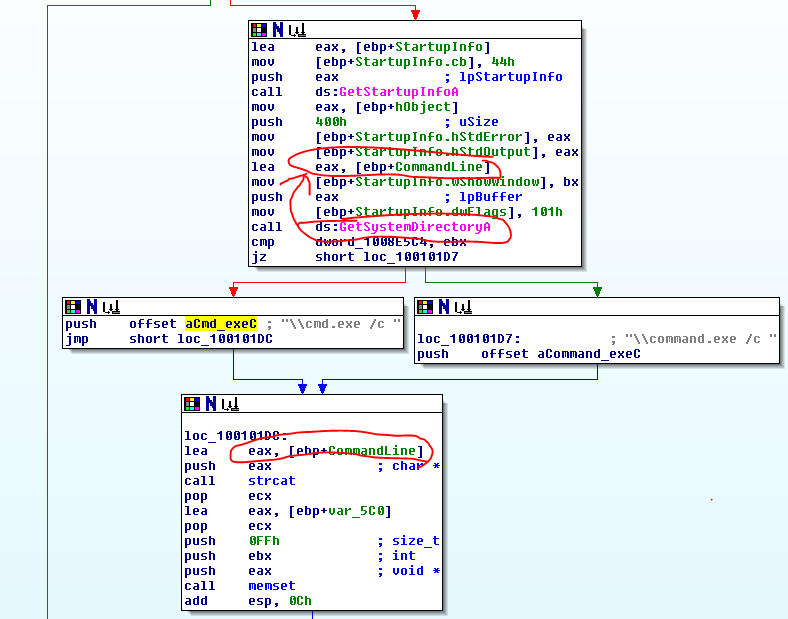

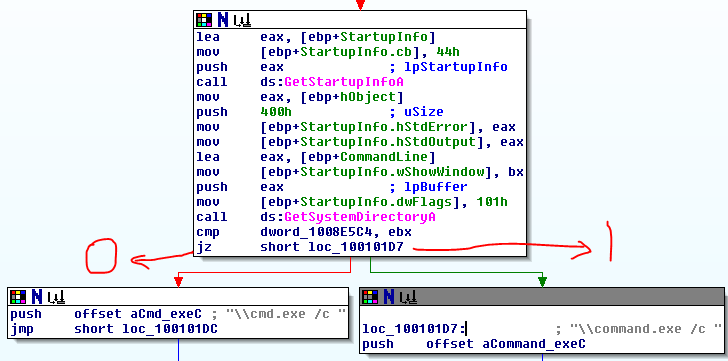

Question 8: What is happening in the area of code that references \cmd.exe /c?

This area of code seems to be used for creating a string that will call cmd.exe on the user’s system, possibly to get a reverse shell. In the screenshot below, the variable “CommandLine” in the top box gets assigned the value of the “GetSystemDirectoryA” function. The next step after the cmd.exe push concatenates the CommandLine variable from before with the command for cmd.exe, creating a command to open a shell (i.e. “C:\Windows\System32\cmd.exe /c”.

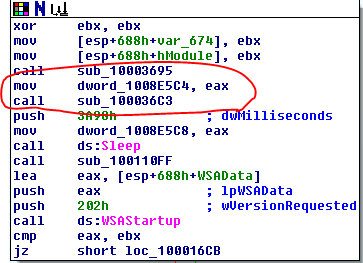

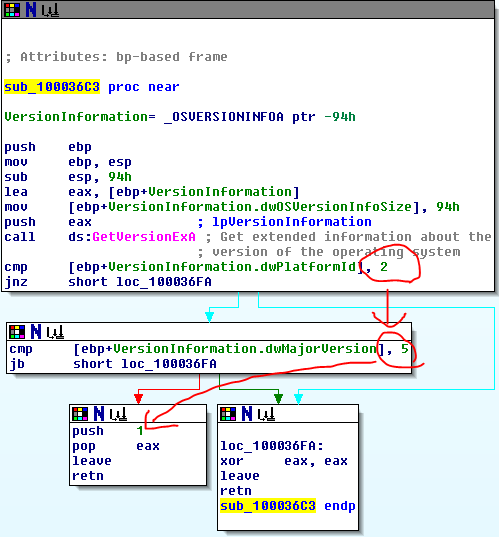

Question 9: In the same area, at 0x100101C8, it looks like dword_1008E5C4 is a global variable that helps decide which path to take. How does the malware set dword_1008E5C4? (Hint: Use dword_1008E5C4’s cross-references.)

The malware assigns a value to dword_1008E5C4 at the beginning of subroutine 10001656 at the very beginning of the program. It assigns the value of eax to dword_1008E5C4 and then calls sub_100036C3, which seems to gather information about the operating system. In the 2nd screenshot below, the subroutine will return 1 if the platform ID == 2 and MajorVersion == 5, else it will return 0. This all comes together to decide which version of the command prompt text to use based on the operating system of the computer. In screenshot 3, we see that if it returns 1 it will use “command.exe /c” and it if returns 0 it will use “cmd.exe /c”.

Question 10: A few hundred lines into the subroutine at 0x1000FF58, a series of comparisons use memcmp to compare strings. What happens if the string comparison to robotwork is successful (when memcmp returns 0)?

If the comparison is successful, it calls the subroutine sub_100052A2, where it queries a registry value at “SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion” for the value of the “WorkTime” key. Once it has the value, it converts it to an integer and pushes it in the format “\r\n\r\n[Robot_WorkTime :] %d\r\n\r\n” through an open network socket. It then does the same thing for the “WorkTimes” key.

Question 11: What does the export PSLIST do?

It first queries the OS version using the same sub_100036C3 as before and continues on the version is 5,2 (it just returns if the version is not 5,2). It then checks the length of a string it has been given. If the length is not equal to zero, it calls sub_10006518 where it searches through active processes trying to find a match. If the string length is equal to zero, then it does similar, but returns a list of all active processes.

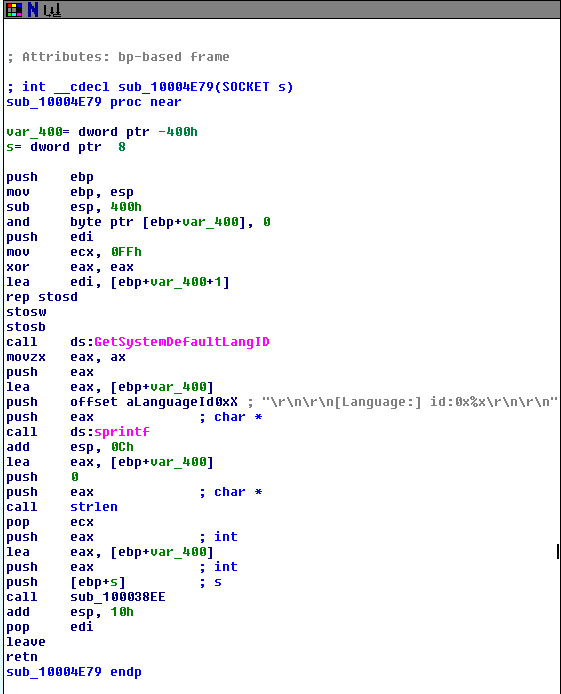

Question 12: Use the graph mode to graph the cross-references from sub_10004E79. Which API functions could be called by entering this function? Based on the API functions alone, what could you rename this function?

This function could call the “GetSystemDefaultLangID”, “sprintf”, “strlen”, and “sub_100038EE” functions. It could be named to match the function it calls or something similar to “GetDefaultLanguage”.

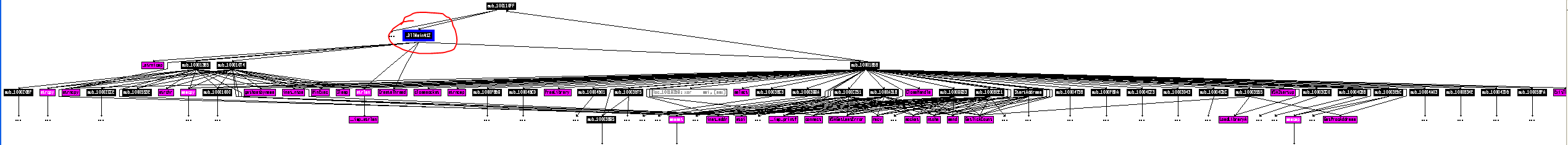

Question 13: How many Windows API functions does DllMain call directly? How many at a depth of 2?

The DLLMain function calls CreateThread, strncpy, strlen, and _strnicmp.

At a depth of two, DLLMain calls 33 total API functions including Sleep and a variety of network-related functions like socket, connect, recv, and send. The screenshot below shows all of the functions (API functions are pink) with DLLMain circled in red for reference.

Question 14: At 0x10001358, there is a call to Sleep (an API function that takes one parameter containing the number of milliseconds to sleep). Looking backward through the code, how long will the program sleep if this code executes?

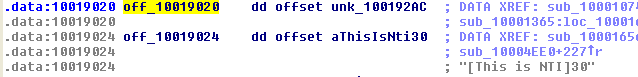

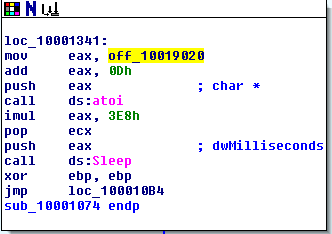

In this section, eax is first given the value of the string at 0x10019020 – “[This is NTI]30”. It then adds 0Dh (13) to the value, setting the string as “30”. In the next few steps it converts the string “30” to the integer 30 and multiplies it by 3E8h (1000). Judging by this, the program will sleep for 30000 seconds or 30 seconds.

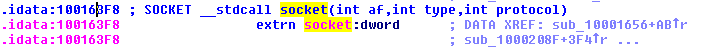

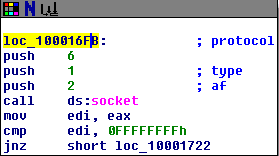

Question 15: At 0x10001701 is a call to socket. What are the three parameters?

The three parameters of socket are all integers: af, type, and protocol. In this program, they’re passed the values 2, 1, and 6.

Question 16: Using the MSDN page for socket and the named symbolic constants functionality in IDA Pro, can you make the parameters more meaningful? What are the parameters after you apply changes?

Yes, after the changes the parameters are changed to AF_INET (af), SOCK_STREAM (type), and IPPROTO_TCP (protocol).

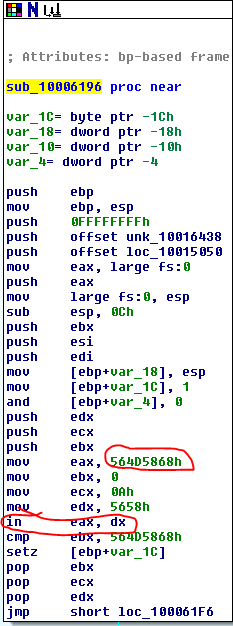

Question 17: Search for usage of the in instruction (opcode 0xED). This instruction is used with a magic string VMXh to perform VMware detection. Is that in use in this malware? Using the cross-references to the function that executes the in instruction, is there further evidence of VMware detection?

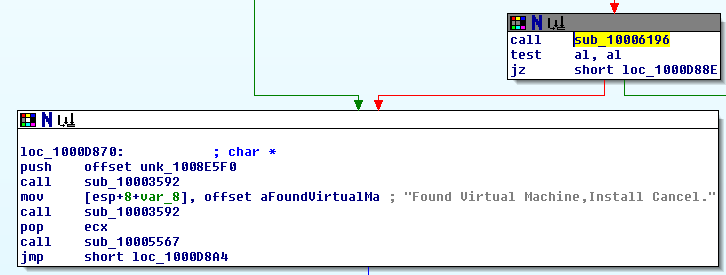

Yes, we find the “in” instruction in the subroutine sub_10006196. The instructions here copy the hex value 564D5868h into eax (which is VMXh in ASCII) and then call “in” on eax. There are cross-references to 3 functions in the program that all call this subroutine and they all include the string “Found Virtual Machine,Install Cancel.”.

Question 18: Jump your cursor to 0x1001D988. What do you find?

Starting at 0x1001D988 we see a list of readable ASCII characters, followed by a string of zeroes, and then a very long list of something IDA doesn’t seem to have recognized and labeled “? ;”.

Question 19: If you have the IDA Python plug-in installed (included with the commercial version of IDA Pro), run Lab05-01.py, an IDA Pro Python script provided with the malware for this book. (Make sure the cursor is at 0x1001D988.) What happens after you run the script?

I don’t have the Pro version and a few quick Google searches says the free version doesn’t support IDA Python, so we’ll skip this question.

Question 20: With the cursor in the same location, how do you turn this data into a single ASCII string?

Pressing “A” tells IDA to combine as many ASCII characters as it can until the next empty space character.

Question 21: Open the script with a text editor. How does it work?

The script Lab05-01.py uses the “ScreenEA” function to get the current position of the cursor in IDA. It then iterates through the next 0x50 bytes and uses an XOR to compare each byte to 0x55, then uses PatchByte to merge them all together on one line.